Opinion: Strategy of Semi-Automatically Annotating a Full-Text Corpus of Genomics & Informatics

Article information

Abstract

There is a communal need for an annotated corpus consisting of the full texts of biomedical journal articles. In response to community needs, a prototype version of the full-text corpus of Genomics & Informatics, called GNI version 1.0, has recently been published, with 499 annotated full-text articles available as a corpus resource. However, GNI needs to be updated, as the texts were shallow-parsed and annotated with several existing parsers. I list issues associated with upgrading annotations and give an opinion on the methodology for developing the next version of the GNI corpus, based on a semi-automatic strategy for more linguistically rich corpus annotation.

The Current Status of GNI Corpus 1.0

Genomics & Informatics (NLM title abbreviation: Genomics Inform) is the official journal of the Korea Genome Organization. A prototype version of the full-text corpus of Genomics & Informatics, called GNI version 1.0, has been recently archived in the GitHub repository [1, 2]. As of July 2018, 499 Part-of-Speech (POS)-tagged full-text articles are available as a corpus resource. Although there has been valuable work done on annotating abstracts, there are differences between abstracts and full-text articles from a natural language processing (NLP) perspective [3].

Now that a prototype GNI corpus has been constructed, we can obtain basic descriptive statistics, which are statistics that do not seek to test for significance. The most basic statistical measure is a frequency count: a simple tallying of the number of instances of something that occurs in a corpus.

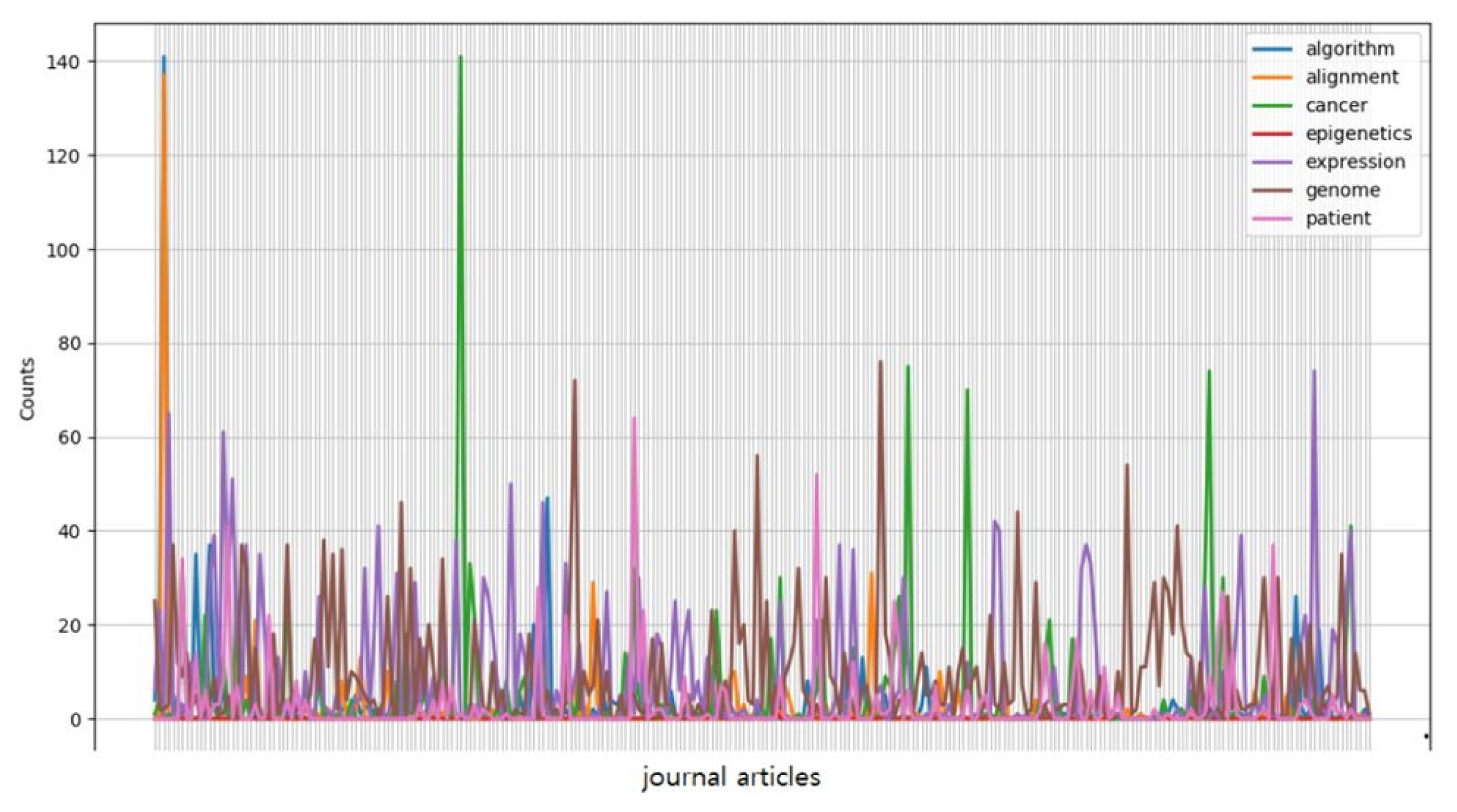

The plot in Fig. 1 was based on a conditional frequency distribution of exemplary keywords—algorithm, alignment, cancer, epigenetics, expression, genome, and patient—where the counts being plotted are the number of times the word occurred in each of the randomly chosen articles from Genomics & Informatics.

Beyond Descriptive Statistics

To better understand the data arising from Genomics & Informatics, annotated corpora are a critical component of biomedical NLP research. Such systems must be trained on sets of examples with known outputs, such that annotated corpora provide the training data vital to the construction of modern NLP systems.

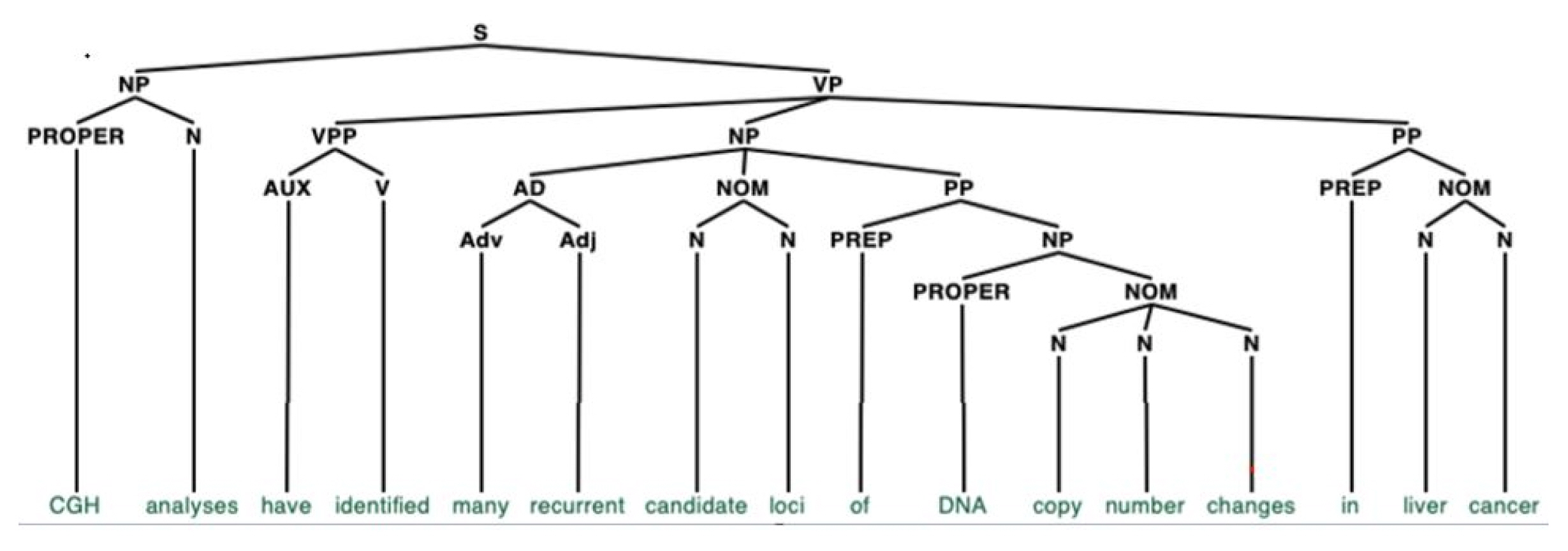

Fig. 2 shows a parsing tree of an exemplary sentence extracted from the GNI corpus “comparative genomic hybridization analyses have identified many recurrent candidate loci of DNA copy number changes in liver cancer.” [4]. However, to obtain a deeper level of linguistic information, such as this, and to fully utilize the GNI corpus, accuracy of the annotations is vital. We estimate that the accuracy of POS tagging in the current version of GNI corpus is 96.8%, as we only utilized existing shallow parsers [5], without manual checking. These parsers are only used to perform superficial syntactic analysis. The problem of text segmentation is also non-trivial, where text segmentation is the process of dividing written text into meaningful units, such as words and sentences. At this moment, approximately 96.1% of the sentences are correctly segmented. This is mainly due to the heavy use of website addresses, float numbers, abbreviations, hyphenated words, figure and table numbers, and gene names in the journal articles.

A parsing tree for an exemplary sentence from the dataset “comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analyses have identified many recurrent candidate loci of DNA copy number changes in liver cancer.” The nodes in capital letters represent a part of speech for each word in the sentence (e.g., N for noun, V for verb, Adj for adjective).

Other issues with tagging accuracy involve optical character recognition (OCR) errors and ungrammaticality. Some of the articles published before 2007 were in image format, such that conversion of images into machine-encoded text was necessary. However, OCR recognition errors were unavoidable, and the noise induced by these errors presented thorny issues to downstream standard text analysis pipelines, including tokenization, sentence boundary detection, and POS tagging, that attempted to make use of such data. Furthermore, a small number of the articles in earlier volumes contain text that is mildly ungrammatical [6]—i.e., text that is well formed yet contains the grammatical errors that are routinely produced by both native and non-native speakers of a language.

Currently, we are annotating our corpus with information about ungrammaticality as follows: words or phrases are marked as ungrammatical (indicated in square brackets) if the phrase needs to be repaired; the original sentence is retained in the corpus, but the input to the parsers does not include ungrammatical parts. Incomplete coverage and incorrect analyses should be addressed through customized preprocessing software tools, after which the process undergoes several cycles of parsing and checking.

Eventually, the automatically annotated corpus needs to be consistently updated by trained human annotators. However, manual corpus annotation is time-consuming and prone to inconsistencies. Our method should be designed to build and improve the annotated corpus, with a diminishing amount of manual-checking.

Thus, customized preprocessing software tools should be developed and upgraded in two separate stages: preparation and analysis of the transcripts for the software tools and a checking and update loop to enhance the tools. I suggest that several rounds of hackathon conferences be organized, hopefully, by Korea Genome Organization or other bioNLP communities. In doing so, customized annotation tools should be developed by fully adopting the methodologies described in recent studies on artificial neural network for NLP [7–11].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ewha Womans University (1-2018-0698-001-1).

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.