Chromothripsis in Treatment Resistance in Multiple Myeloma

Article information

Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant disease caused by an abnormal proliferation of plasma cells, of which the prognostic factors include chromosomal abnormality, β-2 microglobulin, and albumin. Recently, the term chromothripsis has emerged, which is the massive but highly localized chromosomal rearrangement in response to a one-step catastrophic event. Many studies have shown an association of chromothripsis with the prognosis in several cancers; however, few studies have investigated it in MM. Here, we studied the association between chromothripsis-like patterns and treatment resistance or prognosis. First, we analyzed nine MM cell lines (U266, MM.1S, RPMI8226, KMS-11, KMS-12-BM, KMS-12-PE, KMS-28-BM, KMS-28-PE, and NCI-H929) and bone marrow samples of four patients who were diagnosed with MM by next-generation sequencing-based copy number variation analysis. The frequency of the chromothripsis-like pattern was observed in seven cell lines. We analyzed the treatment-induced chromothripsis-like patterns in KMS-12-BM and KMS-12-PE cells. As a result, breakpoints and chromothripsis-like patterns were increased after drug treatment in the relatively resistant KMS-12-BM. We further analyzed the patients’ results according to the therapeutic response, which was divided into sensitive and resistant, as suggested by the International Myeloma Working Group. The chromothripsis-like pattern was more frequently observed in the resistant group. In the sensitive group, the frequency of the chromothripsis-like pattern decreased after treatment, whereas the resistant group showed increased chromothripsis-like patterns after the treatment. These results suggest that the chromothripsis-like pattern is associated with treatment response in MM.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant disease caused by an abnormal proliferation of plasma cells [1]. According to the 2014 Ministry of Health and Welfare Cancer Registration Statistics, MM is the third most common cancer among hematologic malignancies in Korea [2]. Recently, the survival rate has been increasing due to the development of various types of new drugs and the therapeutic options for MM have been characterized by proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib and carfilzomib) and thalidomide analogs [3, 4]. However, MM still remains an incurable cancer, since most MM patients eventually develop drug resistance and die from the disease [5].

Despite many advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of MM and the development of promising new therapies, only 25% to 35% of patients respond to treatment [6]. With regard to classification, prognostic determinants are usually associated with baseline clinicopathological features of aggressiveness of the disease, such as high β2 microglobulin and albumin [7, 8]. Besides the clinical classification, risk prediction includes chromosomal abnormalities, such as hyperdiploidy and rearrangements, which are already known to be very important for the prognosis, because such complex chromosomal rearrangements are frequently observed [8, 9].

About 40% of MM cases have chromosomal translocations, including CCND1, CCND3, MAF, MAFB, WHSC1 (also known as MMSET), and FGFR3, which are overexpressed through rearrangements in the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) locus [10]. As the disease progresses, MM cells accumulate additional genetic changes, such as loss of RB1 and TP53 and increased 1q21 and 9q34 [11].

MM is divided into two major categories: hyperdiploid MM (h-MM) and non-hyperdiploid MM. The ploidy categories are stable over time such that patients with h-MM usually remain hyperdiploid over the course of the disease [8, 12].

The term ‘chromothripsis,’ which is the massive but highly localized chromosomal rearrangement in response to a one-step catastrophic event, rather than an accumulation of a series of subsequent and random alterations, has recently emerged [13]. Chromothripsis has been reported in almost all cancer types, with a prevalence of 2% to 3% (with an incidence of ∼25% in bone cancers) [14]. Chromothripsis is associated with the development of high-grade cancers and more aggressive tumors [13, 15].

The causes and consequences of chromothripsis might be exploited by the use of molecularly targeted therapies, such as epidermal growth factor receptor‒targeted therapy for the treatment of glioblastoma [16]. Chromothripsis affects the functions and expression of a considerable number of genes, and this could be associated with the response to particular drugs [17].

Chromothripsis is defined by the three following major features [18, 19]: (1) localized rearrangements in limited areas of one or several chromosomes, (2) copy number states that suddenly oscillate between areas of normal heterozygosity and loss of heterozygosity, and (3) multiple chromosome fragments rearranged in random orientation and order.

Despite chromothripsis being widely reported in many cancers, the exact criteria and the role of copy number alterations have yet to be standardized [16]. Previous studies have shown a poor prognosis in patients with chromothripsis and that chromothripsis is associated with the prognosis in several cancers, including malignant melanoma, neuroblastoma, and colorectal cancer. These findings suggest that chromothripsis is a tool for predicting the prognosis of patients [20].

The aim of this study is to confirm the association of chromothripsis with drug resistance and the prognosis in patients with MM. Although previous studies have been performed in solid tumors, few studies have examined chromothripsis in MM [14, 20, 21], and we hypothesized that chromothripsis is associated with the prognosis of patients who are diagnosed with MM.

Methods

MM cell lines

The human MM cell lines U266, MM.1S, RPMI8226, and NCI-H929 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The KMS-11, KMS-12-BM, KMS-12-PE, KMS-28-BM, and KMS-28-PE cell lines were purchased from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (JCRB, Osaka, Japan). All MM cell lines except NCI-H929 were cultured in RPMI1640 (GIBCO, Thermo Fisher, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Thermo Fisher) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (GIBCO, Thermo Fisher).

Bone marrow samples and plasma cell sorting

Bone marrow aspirates from four MM patient samples were obtained at the diagnosis and after chemotherapy. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (NCC2016-0279) of the National Cancer Center, Korea.

Bone marrow cells were obtained and separated from heparin-treated blood through density gradient centrifugation (2,200 rpm, 20 min, break 0) using Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway).

Bone marrow plasma cells were enriched using the EasySep Human Whole Blood and Bone Marrow CD138 Positive Selection kit (Stemcell Technologies, Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) using EasySep magnets (Stemcell Technologies) or CD138 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany) using MS columns (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FITC-Mouse Anti-Human CD138 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) antibody was used to stain the cells, and the cells were applied directly to flow cytometric analysis using a FACSVerse.

Drug treatment and cell viability assay

Bortezomib (BTZ) was purchased from Selleckchem (Selleck Chemicals LLC, Houston, TX, USA), dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, and stored at ‒80°C. KMS-12-BM and KMS-12-PE were seeded into T175 flasks (SPL Life Sciences, Pochoen, Korea) at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells overnight before treatment. BTZ was administered to a final concentration of 1 nM without dose escalation on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. After 48 h of drug treatment, the media was replaced.

Cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates (SPL Life Sciences) and treated with BTZ for 24 h. For the cell viability assay, each well was treated with the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) for 1 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Versa Max ELISA Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The experiments were performed in duplicate.

Next-generation sequencing‒based copy number variation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from cell pellets and frozen patient bone marrow samples using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of DNA was measured using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA), and bone marrow samples were stored at ‒80°C until further use.

Shearing was performed using the M220 Focused ultrasonicator (Covaris, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA) (peak power, 55 W; duty factor, 20; cycle/burst, 200; time, 3 min). The library prep was then used with the Accel-NGS2S Plus Library kit (Swift Biosciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) sequencing was performed in the 75-bp single-end mode of a NextSeq500 instrument. The human reference (hg19) was aligned with the BWA-mem 0.7.5a version. PCR deduplication with Picard (ver. 1.96) was conducted, and only the reads with a mapping quality of 60 were selected. GC content and mappability correction were performed using Q-seq (v.1.8.0) R-packaged and high-order artifacts were removed using the principal component analysis method. The reference samples included data on 20 females that were confirmed to be normal and were used for the array results. Data segmentation was performed using the circular binary segmentation (CBS) algorithm and DNA copy (v.1.38.1).

After alignment, the sequence read was counted in chromosome units and compared with the control set to obtain the z-score, which determined whether or not aneuploidy was present at the chromosome level. In order to determine the presence of a microdeletion or duplication, the human genome reference sequence was further divided into several 10,000-segment bins, and the number of sequence readings aligned in the bin was counted and compared with the control set to obtain the z-score.

Comparison of chromothripsis-like pattern analysis

Genes included in the locus were identified in the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) human genome.

We confirmed the similarity between the chromothripsis-like patterns identified in this study and the results reported in other studies through chromothripsisDB, which is a database for the identification of chromothripsis in many cancers.

Results

Frequency of copy number alterations in MM cell lines

We analyzed the frequency of copy number alterations (CNAs), including mosaicism in 9 MM cell lines. Among them, chrs 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, and X were the sites with the most frequent CNAs in the MM cell lines (Fig. 1A). Among the MM cell lines, the frequency of CNAs (66.67% to 95.83%, median: 83.33%) in MM.1S and KMS-12-PE cells was relatively low (16/24 chromosomes), and the frequency of CNAs in U266 and RPMI8226 cells was high (23/24). U266 cells showed fewer CNAs, but alterations were observed in almost all chromosomes except one.

Analysis of frequency of copy number alterations in multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines. (A) Number of chromosomal copy number alterations in MM cell lines. The red dotted line box indicates a chromosome with a high frequency of copy number alterations in MM cell lines. (B) A chromosome arm-specific copy number alterations in the form of a heatmap. (C) Average value of copy number (CN) for each chromosome arm (normal range, 1.5‒2.5 copies).

The chromosomes were divided into arms to confirm the trend of CNAs. According to the algorithm, if the copy number was 2.5 or more, it was considered an amplification, and if the copy number was 1.5 or less, it was considered a loss. Analysis of the tendency of CNAs showed that more CNAs were observed in the q arm than in the p arm (Fig. 1B and 1C).

To identify the chromothripsis-like pattern in MM cell lines, the copy number oscillation state was identified. If there were more than 10 breakpoints in a single chromosome, it was considered a chromothripsis-like pattern [14, 22]. The chromosome where the chromothripsis-like pattern was most frequently observed was chr 1 in 5 cell lines, followed by chrs 11 and 12 in three cell lines. On the other hand, chrs 4 and 14 showed fewer chromothripsis-like patterns. Of the cell lines, KMS-11 cells most frequently had a chromothripsis-like pattern (5/24 chromosomes), followed by RPMI8226 (4/24 chromosomes).

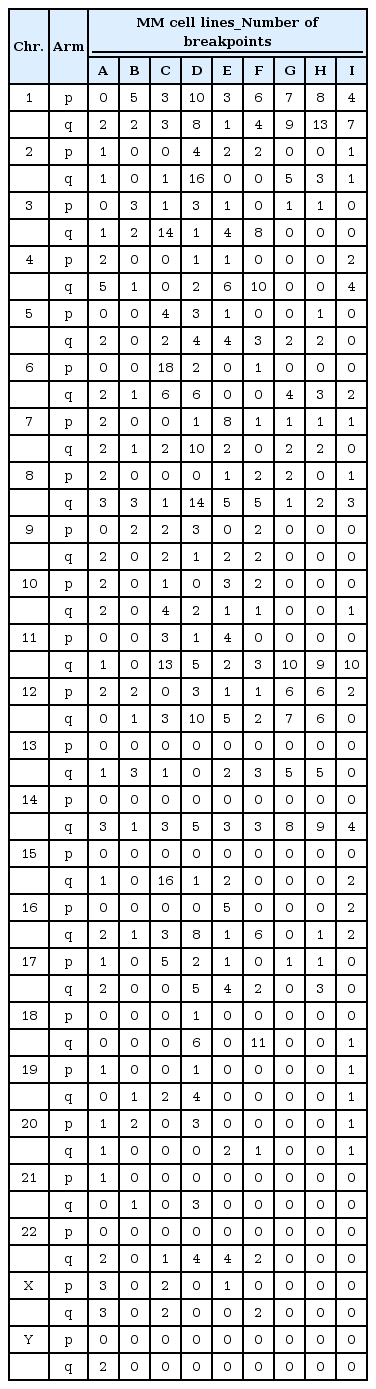

The chromosome arms were analyzed to confirm the trend of the chromothripsis-like pattern. As a result of the analysis, breakpoints were observed more than twice as often in the q arm than in the p arm (p: 209 breakpoints, q: 502 breakpoints) (Table 1). Breakpoints were also most frequently observed in chr 1.

Chromothripsis-like pattern according to drug treatment

Among the 9 MM cell lines, in particular, KMS-12-BM and KMS-12-PE cells, derived from the same origin, showed different CNA patterns. Thus, changes in CNAs were further analyzed in these cell lines by comparing CNAs after BTZ treatment, which has the most clinical relevance. In order to analyze the drug treatment-induced chromothripsis-like pattern, cell pellets were all collected at the time of treatment. The time frame of the treatment was the same as the schedule in actual clinical practice. Although the cell lines were derived from the same origin, the drug response between the two cell lines was different. In the case of KMS-12-BM, there was no difference in cell viability in the treatment group compared to the control, but in the case of KMS-12-PE, there was a sharp decrease in viability in the treatment group (Fig. 2A‒2D). Analysis of chromothripsis and breakpoints was performed in the cell pellet from Day 11, which represented the end of one cycle of drug treatment.

Comparison of cell viability changes of KMS-12-BM and KMS-12-PE following treatment of bortezomib (BTZ). (A) Morphological changes of KMS-12-BM cell line according to BTZ treatment. (B) Comparison of cell viability with BTZ treatment of KMS- 12-BM cell line. (C) Morphological changes of KMS-12-PE cell line according to BTZ treatment. (D) Comparison of cell viability with BTZ treatment of KMS-12-PE cell line. (E, F) Comparison of copy number alterations control and drug treatment according to treatment response.

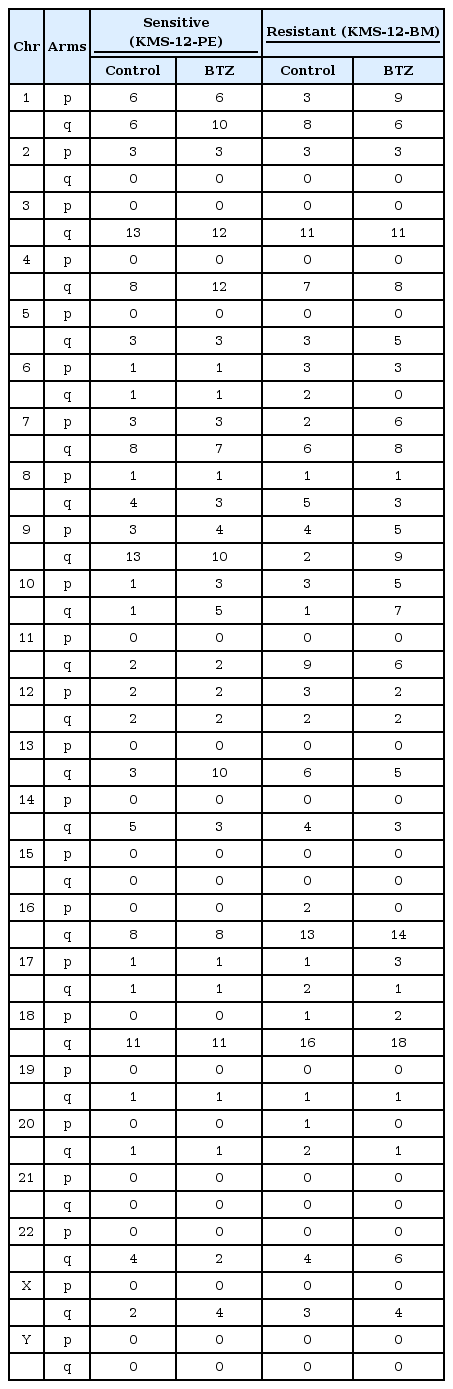

Compared to the control group, KMS-12-PE, which was considered the drug-sensitive group, did not show any difference in breakpoint events or chromothripsis-like pattern. On the other hand, in the case of drug-resistant KMS-12-BM, breakpoints and chromothripsis-like patterns were increased after drug treatment (Table 2). On analyzing the chromosome arms, the frequency of breakpoints was increased in the q arm versus p arm (p: 111 breakpoints, q: 430 breakpoints).

Of the total chromosomes, the copy number state changed significantly after drug treatment in chr 9. Chr 9 was then further analyzed to compare the gain and loss of genes related to MM (Fig. 2E, F).

A total of 29 of 285 genes that were associated with MM were located in chr 9 [23-31]. Gene gain and loss in chr 9 were analyzed and compared according to drug response, and it was observed that KMS-12-BM, which is resistant to BTZ, showed an increase of CNAs after BTZ treatment (Table 3).

Chromothripsis-like pattern by NGS-based copy number variation analysis in MM patient samples

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays are widely used for the analysis of CNAs, including chromothripsis-like patterns. However, the minimum amount of DNA required for SNP array analysis is considerably high. Thus, NGS-based copy number variation (CNV) analysis, which requires a relatively small quantity of DNA, was adopted in the study.

To determine the changes in CNAs for drug response, NGS-based CNV analysis of pre- and post-treatment specimens from 4 patients with BTZ treated was performed. The patients were also divided into sensitive (stringent complete remission, CR, near complete remission, very good partial response, and partial response) and resistant (stable disease and progressive disease) according to the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria (Table 4). Patients in each of the two groups showed changes in CNAs before and after treatment. After treatment, the frequency of CNAs decreased in the sensitive group, whereas it increased in the resistant group compared to pre-treatment (Fig. 3A and 3B).

Comparison of changes in patient’s copy number (CN) state in pre- and post-treatment according to treatment response. (A) A chromosome arm-specific CN alterations in the form of a heatmap. (B) CN for each chromosome arm in each patient’s specimen (normal range, 1.5‒2.5 copies). (C) Comparison of breakpoints in preand post-treatment of multiple myeloma patients according to treatment response.

No chromothripsis-like pattern was observed in four patients. However, it was shown that the the number of breakpoint was high in chr 4q of pt 4. In the comparison of chromosome by arms, breakpoints were more frequent in the q arm, as in the previous results (p: 36 breakpoints, q: 82 breakpoints).

The association of MM-related genes in the 1q21 region on chr 1, in which the chromothripsis-like pattern was frequently observed, was shown again, as in the previous result. There are 29 genes that are associated with MM among the total 218 genes that coded for proteins in the locus, and it was known that the prognosis is poor when all of these genes are amplified [32-39]. Then, the candidate genes in chr 1 were further analyzed for chromothripsis-like patterns (Fig. 3C).

Comparison of other chromothripsis-like pattern studies

Comparing the results with the chromothripsis-like patterns registered in chromothripsisDB, the same results were observed for chrs 1q, 13q, and 16q in this study. Even though the chromothripsis-like patterns in chrs 2q, 3q, 10q, 12q, and 17p were reported in chromothripsisDB, the patterns were not the same in this study. However, the chromothripsis-like patterns in chrs 6q, 9p, 22q, Xp, and Xq were unique in this study.

Discussion

In the present study, the frequency of CNAs in MM cell lines and patient samples was analyzed and compared according to treatment response and difference in CNAs.

Chromosomal aberrations were least frequent in MM.1S and KMS-12-PE cells among the MM cell lines and most frequent in RPMI8226. The U266 cell line had fewer CNAs, but alterations were observed in almost all chromosomes except one chromosome. These results suggest that CNAs might be related with treatment response. MM.1S is well known as a dexamethasone-sensitive cell line, while RPMI-8226 and U266 have previously been reported to establish resistant cells against several drugs in previous studies [40,41].

To determine whether chromothripsis was induced by drug treatment, two cell lines (KMS-12-BM and KMS-12-PE) derived from the same origin were used for analysis after BTZ treatment. As a result, it was found that the frequency of breakpoints and chromothripsis-like patterns was increased after drug treatment in the resistant group, and the frequency was higher in the q arm, which is relatively longer. On the other hand, no significant difference was observed between pre- and post-treatment in the sensitive group.

In patient BM samples, the frequency of CNAs was high in the resistant group. In addition, when the patients were compared to their BM samples between pre- and post-treatment, the number of breakpoints was decreased in the sensitive group but increased in the resistant group. So, these results suggest that chromothripsis could be associated with therapeutic response. Also, it means that the drug probably could induce chromothripsis, depending on the drug administration in the clinic.

When the chromosomal analysis was performed, the frequency of chromothripsis-like patterns in chr 1 was the highest in resistant patients and MM cell lines. A previous study also reported that the frequency of CNAs was highest in chr 1. Especially, elderly patients aged 65 years or older are more likely to have abnormalities when they are treated with novel therapies [1]. Also, the copy number of the genes in the 1q21 region, which showed the most chromothripsis-like patterns, was amplified in resistant patients. There are more studies that have reported similar findings as our results [32-39, 42, 43]. Chr 4, where the MMSET and FGFR3 genes are located, and chr 14, where the IgH gene is located, showed fewer chromothripsis-like patterns in a previous study [44]. These results mean that drug treatment to patients might be able to affect the structure of a particular chromosome.

The chromothripsis-like pattern has been commonly observed in 1q, 13q, and 16q as compared to the chromothripsis-like pattern confirmed in this study and similar results in other studies [22, 45]. Unlike the result from other studies, chromothripsis-like patterns in 2q, 3q, 10q, 12q, and 17p were not observed in this study. However, unique chromothripsis-like patterns were observed in this study for 6q, 9p, 22q, Xp, and Xq.

The advantage of using an SNP array is that it has a wide detection range of abnormalities by evaluating abnormalities in entire chromosomes with high resolution. However, there is a disadvantage, in that it requires a high quantity of DNA. Therefore, NGS-based CNV, which has relatively low resolution but requires low DNA input, could replace the SNP array. Based on the analysis of our results, NGS-based CNV is not worse than the SNP array and could replace the SNP array test to detect chromothripsis-like patterns.

Although the number of analyzed samples in this pilot study was small, we showed that the chromothripsis-like pattern was associated with the patient treatment response and that the drug treatment might affect the structure of the chromosome. Finally, this study suggests that a chromothripsis-like pattern could be induced by drug treatment in MM patients and that chromothripsis might be a good predictor in the diagnosis of MM patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (2014R1A2A2A01002553).

Notes

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: SYK

Formal analysis: KJL, KHL

Funding acquisition: SYK

Methodology: KJL, KHL, KAY, JYS

Writing - original draft: KJL, KHL, KAY, SYK

Writing - review & editing: EL, HL, HSE, SYK