In Silico Signature Prediction Modeling in Cytolethal Distending Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Strains

Article information

Abstract

In this study, cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) producer isolates genome were compared with genome of pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli strains. Conserved genomic signatures among different types of CDT producer E. coli strains were assessed. It was shown that they could be used as biomarkers for research purposes and clinical diagnosis by polymerase chain reaction, or in vaccine development. cdt genes and several other genetic biomarkers were identified as signature sequences in CDT producer strains. The identified signatures include several individual phage proteins (holins, nucleases, and terminases, and transferases) and multiple members of different protein families (the lambda family, phage-integrase family, phage-tail tape protein family, putative membrane proteins, regulatory proteins, restriction-modification system proteins, tail fiber-assembly proteins, base plate-assembly proteins, and other prophage tail-related proteins). In this study, a sporadic phylogenic pattern was demonstrated in the CDT-producing strains. In conclusion, conserved signature proteins in a wide range of pathogenic bacterial strains can potentially be used in modern vaccine-design strategies.

Introduction

The co-evolution of pathogenic bacteria and their hosts leads to the generation of functional pathogen-host interfaces. Well-adapted pathogens have evolved a variety of strategies for manipulating host cell functions to guarantee their successive colonization and survival. For instance, a group of gram-negative bacterial pathogens produces a toxin, known as cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) [1]. Among the vast majority of CDT producers are Escherichia coli, which is commonly found in the intestines of humans and other mammals. Most E. coli strains are harmless commensals; however, some isolates can cause severe diseases and are designated as pathogenic E. coli. Among the various pathogenic E. coli strains, some have acquired virulence determinants through the horizontal transfer of genes, such as the cdt genes encoding CDTs. CDTs were the first bacterial toxins identified that block the eukaryotic cell cycle and suppress cell proliferation, eventually resulting in cell death. The active subunits of CDT toxins exhibit features of type I deoxyribonuclease-like activity [23].

In this study, comparative genome analysis of CDT-producer E. coli isolates with other pathogenic and commensal strains was performed. Alignments between multiple genomes led to the identification of a set of distinct (“signature”) sequence motifs. These signature sequences could be used to delineate single genomes or a specified group of associated genomes within a desired group, such as the CDT-producing E. coli (the target group in this study). While genomic signatures were conserved in the target group, which they were not conserved or were absent in other related or unrelated genomes (i.e., the background group). From a clinical point of view, conserved signature sequences could offer advantages in predicting and further designing novel CDT inhibitors to vaccine candidates [4].

On the other hand, phylogenic trees can be constructed based on multiple sequence alignments. It is important that phylogeny based on an immense number of genes and whole-genome sequences are more reliable than those based on a single gene or a few selected loci [5]. Phylogenic analysis can provide an overall classification of the target group among the background group. Alignment of whole-genome sequences yields detailed information on specific differences between genomes and, consequently, has shed new insights into phylogenetic relationships in recent years [6789].

In this study, phylogenic relationships of CDT+ strains with other pathogenic and commensal E. coli strains were assessed, and conserved signature genomic regions in the target group (CDT-producers) were annotated. This information could be used for developing molecular diagnostics assays, polymerase chain reaction primer and probe design in modern vaccines.

Methods

CDT+ strains

Several databases were used to identify bacterial strains harboring cdt genes. Data was extracted from the following resources: NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank; EMBL, European Molecular Biology Laboratory; DDBJ, DNA Data Bank of Japan; PDB, Protein Data Bank; RefSeq, NCBI Reference Sequence Database; and UniProtKB, Swiss-Prot Database.

Whole-genome sequences

All genomes analyzed in this study were downloaded from the NCBI file transfer protocol (FTP) site at: ftp://ftp. ncbi.nih.gov/genomes.

Reordering of draft genomes

Ordering and orienting contigs in draft genomes facilitates comparative genome analysis. Contig ordering can be predicted by comparison of a reference genome that is expected to have a conserved genome organization [10]. ProgressiveMauve (version 2.3.1) was used for ordering contigs in draft genomes. Mauve contig mover (MCM) offers advantages over methods that rely on matches in limited regions near the ends of contigs [1112]. The E. coli K-12 MG1655 strain (accession No. NC_000913.3) was used as a reference genome.

The MCM optional parameters were used in this study including default seed weight, use seed families: 15 determine Locally Collinear Blocks (LCBs); LCBs, full alignment, iterative refinement, sum-of-pairs LCB scoring, and min LCB weight: 200.

Multiple genome alignments

In this study, Gegenees software (version 2.2.1) was used for multiple-genome alignments. The software is written in JAVA, and making it compatible with several platforms. Limitations were not observed in the speed calculation, number and memory of the genomes that could be aligned. Gegenees software is also capable of performing fragmented alignments [4]. Multiple alignments of E. coli genomes were created using a fragment size of 200 nucleotides, a step size of 100 parameters, and BLASTN, which was optimized for highly similar sequences.

Phylogenic tree construction

A phylogram was produced in SplitsTree 4, using the neighbor-joining method and a distance matrix Nexus file exported from Gegenees software [13]. E. albertii TW07627 and E. fergusonii ATCC 35469 strains were set as the out-groups.

Identifying conserved signatures

CDT-producing isolates were set as the target group, and all other strains were used as the background group by using the in-group setting tab in Gegenees software. Because of the genomic diversity in CDT-producer E. coli, we repeated this procedure with five different strains, including E. coli 53638, E. coli IHE3034, E. coli RN587/1, E. coli STEC B2F1, and E. coli STEC C165-02, which were defined as separate reference strains.

The biomarker score (max/average) setting was also used. Biomarker scores were drawn graphically and loaded into the tabular view for further data analysis. In the tabular view, a score of 1.0 is the maximum biomarker score and is considered as a signature.

Assembling signature fragments

Several overlapping fragments were obtained, based on the sequences of each reference strain. To facilitate subsequent analysis steps, the overlapping fragments were assembled using DNA Dragon software, version 1.6.0 (http://www.dna-dragon.com/).

The settings were designed with minimum overlaps (100 bases) along the diagonal length, a minimum %-identity of complete overlapping fragments, and 100% full-search parameters.

BLAST

BLAST was done with sequences for each of the five reference strains by using NCBI BLASTX (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to identify the putative protein domains. Furthermore, putative conserved domains were also detected. The results were confirmed using the Uni-ProtKB Bank BLASTX program (http://www.uniprot.org/blast/).

Results

Strains

The sequences of 76 strains were downloaded from the NCBI site. Details regarding genome sizes, %GC content, the number of encoded proteins, encoded genes, genome type, pathotype, serotype, other characteristics, and accession numbers are summarized in Table 1. Most data presented were extracted from NCBI GenBank and UniProt Bank and some information was extracted from original articles [1415]. The genomes of 24 strains were drafted, and a reordering process of the draft genomes was performed. Twenty-five CDT+ E. coli strains were analyzed, including E. albertii TW07627.

Phylogenic analysis

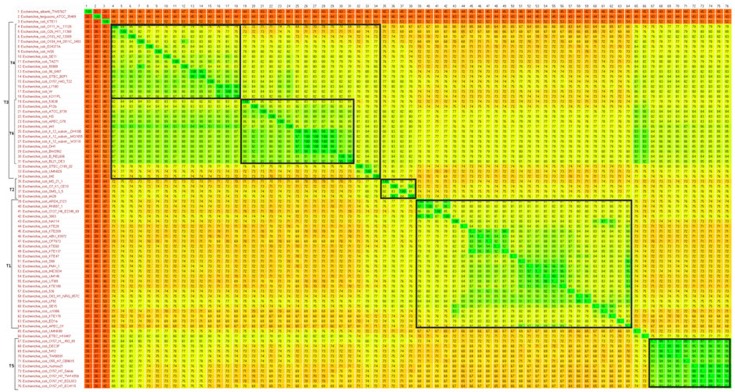

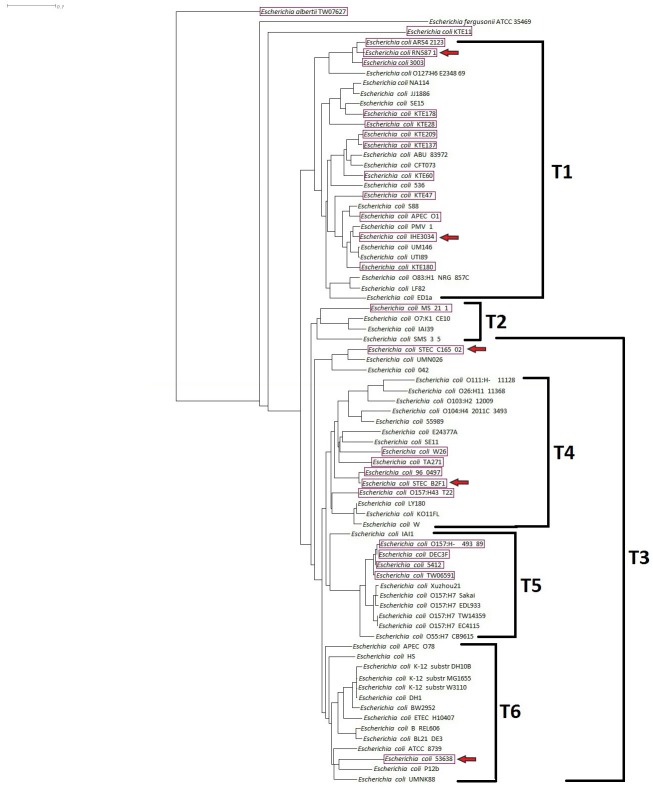

A heat-plot based on a 200/100 BLASTN fragmented alignment drawn with Gegenees software is shown in Fig 1. A phylogenic overview is also shown in the heat-plot. A more detailed phylogram was constructed with SplitsTree 4 software, as shown in Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic heat-plot overview of multiple-genome alignments. A heat plot based on a 200/100 BLASTN fragmented alignment was performed with Gegenees software. Six distinct genomic groups (T1–T6) recognized in cytolethal distending toxin (CDT)+ strains were observed sporadically among the strains that were studied, revealing the heterogeneous genomic nature of CDT-producing Escherichia coli.

Phylogram overview. A phylogram was generated using SplitsTree 4 software, using the neighbor-joining method and a distance-matrix Nexus file exported from Gegenees software. The Escherichia albertii TW07627 and Escherichia fergusonii ATCC 35469 strains were set as out-groups. In addition, six unique groups (T1–T6) were analyzed. In the phylogenetic overview, a sporadic pattern of cytolethal distending toxin (CDT)–producing strains was observed, as were specific clades. These strains were related and their similarities were shown. CDT+ strains are shown in boxes. The Escherichia coli strains that were set as reference strains for biomarker-detection studies are indicated with red arrows.

CDT-producer E. coli strains were displayed a sporadic, phylogenomic pattern in the heat-plot, with a lack of a consensus pattern. Six distinct genomic groups of CDT+ strains (T1 to T6 in Fig. 2) were shown in the phylogram, all of which were sporadic among the strains in Fig 1. As a sporadic pattern of CDT-producing strains was observed in the bacterial population in the phylogram for specific clades, these strains were related and some degrees of similarity were also found.

Signature sequences in the target group

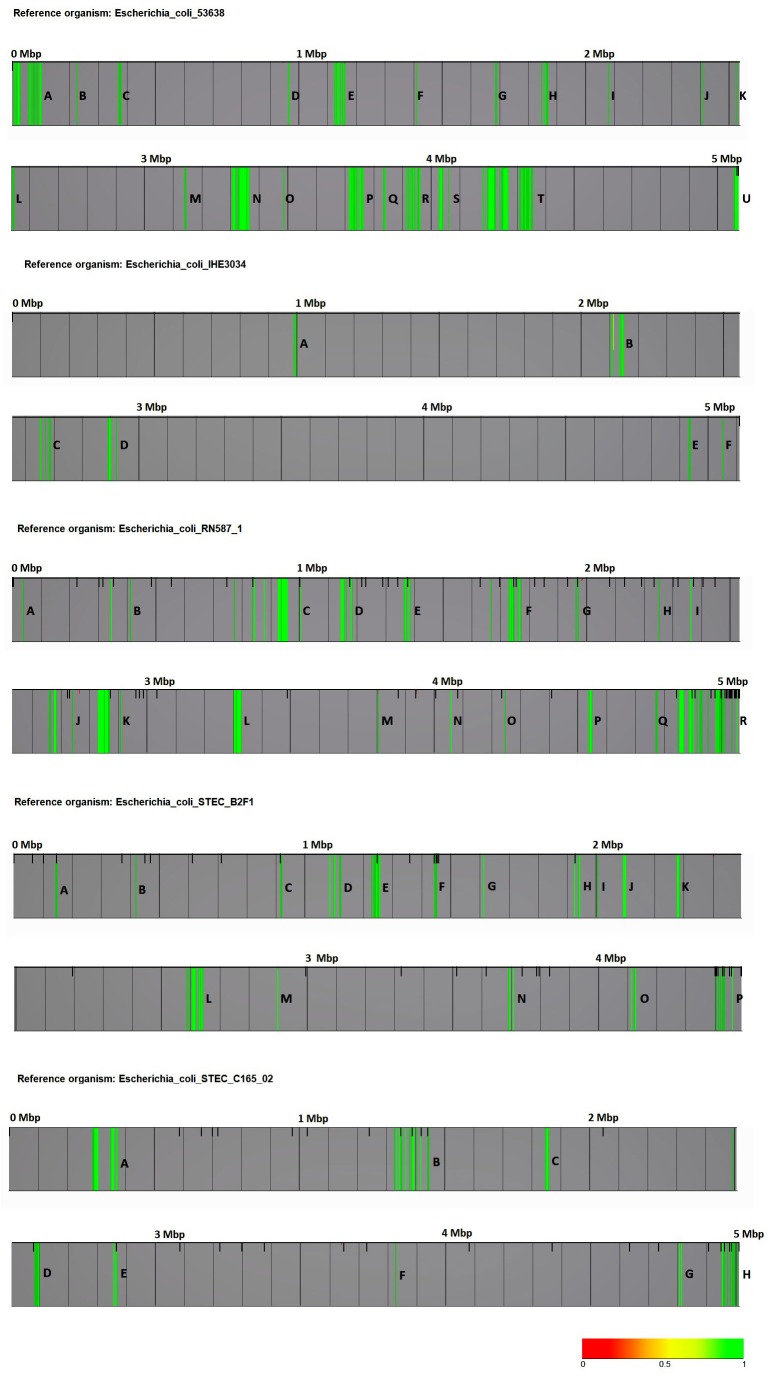

In total, 1,527 fragments representing 3.0% of the E. coli 53638-strain genome were identified as signature sequences. Biomarkers were restricted to 21 highly significant regions, designated A to U. When E. coli IHE3034 was set as the reference strain, 220 signature sequences (0.4%) were detected. Biomarkers were identified in six regions, designated A to F. However, 1,512 (2.9%) signature fragments were obtained, which were restricted to 18 regions (A to R) in the genome of E. coli RN587/1 when it was regarded as the reference strain. Moreover, 620 biomarker fragments (1.2%) were detected in the genome of E. coli STEC B2F1 when it was set as the reference strain, 16 biomarker regions (A to P) were recognized. In addition, when E. coli STEC C165-02 was used as the reference strain, 593 signature fragments (1.1%) were identified, which were restricted to eight regions (A to H). The signature regions for all reference strains are shown in Fig. 3, separately. In addition, the biomarker designation, domain description, BLASTX results and related putative conserved domains for each reference strain are provided in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Biomarker regions. Biomarker regions were illustrated in the whole-genome sequences of five different reference strains including Escherichia coli 53638, E. coli IHE3034, E. coli RN587/1, E. coli STEC B2F1, and E. coli STEC C165-02. The biomarker score (max/average) setting was used. A score of 1.0 is the maximum biomarker score, which was considered to represent a signature sequence, as indicated in green. STEC, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli.

Conserved signature proteins

The most common biomarker proteins were distinguished by comparing BLASTX results for all reference strains fragments (Table 2). The signature proteins identified included: CDT, holin, lambda-family proteins, nuclease, phage integrase family proteins, phage tail tape measure family proteins, putative membrane proteins, regulatory proteins, restriction-modification system proteins, tail fiber assembly proteins, baseplate assembly proteins, tail fiber protein and other prophage tail related proteins, terminuses and transferases. The nucleotide sequences of some proteins including anti-termination proteins, prophage DNA packaging and binding proteins, transposase and DNA transposition proteins, scaffold proteins, recombination-related domains, putative phage-replication proteins, hemolysin, helicase, glycol transferase, and glycohydrolase superfamilies, were detected as biomarkers in the target group, although these BLASTX results were not observed in all reference strains. Presumably, CDT-producer E. coli strains possess several hypothetical proteins whose functions are not yet defined and might be conserved proteins. The existence of these DNA biomarker sequences in reference strains is clear; however, the related proteins in some strains have not been determined.

Significant putative conserved domains and superfamilies

In the era of modern vaccines, finding conserved domains or epitopes has a great therapeutic value. Putative conserved domains were described as non-specific hits (NH), specific hits (SH), and multi-domains (MD), and it was shown in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

The putative conserved domains and superfamilies that were associated with some signature proteins are shown below.

- NH: PRK15251, DUF4102, CdtB, CDtoxinA, INT_P4, HP1_INT_C, Phage_integrase, INT_Lambda_C, Phage_integ_N, Methylase_S, Caudo_TAP, phage_tail_N, Tail_P2_I, gpI, phage_term_2, Terminase_3, Terminase_5, M, Phage_term_smal, COG5525, Terminase_GpA, Phage_Nu1, dexA, Phage_holin_2, DUF3751, Phage_attach, dcm, DNA_methylase, Cyt_C5_DNA_methylase, Dcm, Glycos_transf_2, and CESA_like

- SH: INT_REC_C, PhageMin_Tail, COG4220, Phage_fiber_2, HSDR_N, Glycos_transf_2, GT_2_like_d, PRK-10018, and PLN02726

- MD: PRK09692, int, recomb_XerC, XerD, xerC, HsdS, N6_Mtase, HsdM, hsdM, rumA, P, Terminase_6, COG-5484, PLN03114, COG5301, COG0610, hsdR, PRK-10458, PRK10073, Glyco_tranf_2_3, WcaA, PRK10073, and PTZ00260

- Superfamilies: RICIN superfamily, EEP superfamily, DNA_BRE_C superfamily, DUF4102 superfamily, Phage_integ_N superfamily, MCP_signal superfamily, Methylase_Ssuperfamily, Caudo_TAPsuperfamily, phage_tail_Nsuperfamily, Tail_P2_Isuperfamily, Terminase_3superfamily, Terminase_5superfamily, Phage_term_smalsuperfamily, Terminase_GpAsuperfamily, Phage_Nu1superfamily, DnaQ-like-exosuperfamily, Phage_holin_2superfamily, DUF3751 superfamily, Phage_fiber_2superfamily, Gifsy-2 superfamily, HSDR_Nsuperfamily, Cyt_C5_DNA_methylase superfamily, MethyltransfD12superfamily, Glyco_transf_GTA type superfamily, and Glyco_transf_GTA typesuperfamily

Discussion

The synchronic evolution of bacterial pathogens and virulence-associated determinants encoded by horizontally transferred genetic elements has been observed in several species. However, E. coli is a normal member of the intestinal microflora of humans and animals. E. coli strains have acquired virulence factors by the attainment of particular genetic loci through horizontal gene transfer, transposons, or phages. These elements frequently encode multiple factors that enable bacteria to colonize the host and initiate disease development [16]. CDTs belong to one such class of virulence-associated factors. CDT was first identified in E. coli by Johnson and Lior in 1988 [17]; since then several studies have been reported that CDTs can be produced by intestinal and extra-intestinal pathogenic bacteria [18].

In this study, the genomes of 25 CDT+ E. coli strains were acquired from several gene banks. Multiple genome comparisons with 49 CDT− E. coli strains, including EPEC (enteropathogenic E. coli), ETEC (enterotoxigenic E. coli), STEC (Shiga toxin-producing E. coli), EAEC (enteroaggregative E. coli), EIEC (enteroinvasive E. coli), AIEC (adherent invasive E. coli), UPEC (uropathogenic E. coli), ExPEC (extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli), EHEC (enterohemorrhagic E. coli), environmental strains and commensal strains were performed.

In fact, phylogenic analysis based on whole-genome information is more accurate than those based on one gene or a set of limited genes. In this study, CDT-producing strains were not shown a phylogenomic relationship or pattern. Indeed, while they might carry the same or similar virulence gene sets, they also possess their own divergent genomic structures. This is probably because of their complex and distinct evolutionary pathways, indicating an independent acquisition of mobile genetic elements during their evolution.

The sporadic pattern in the phylogenomic dendrogram confirmed previous findings that CDT+ strains are heterogeneous. The heterogeneous nature of CDT-producing strains might arise from horizontal gene transfer through mobile genetic elements. These genetic exchanges that occur in bacteria provide genetic diversity and versatility [19].

A significant challenge in comparative genomics is the utilization of large datasets to identify specific sequence signatures that are biologically important or are useful in diagnosis [420]. In this study, we define CDT-producing E. coli as the target group and found regions that were conserved that could serve as genomic signatures for the target group. Because of the heterogeneous genomic nature of CDT+ E. coli, five reference strains were selected instead of one, including EIEC, ExPEC, EPEC, STEC B2F1, and STEC C165-02. Moreover, in the phylogenomic overview, these five reference strains were selected from different clades of the phylogenic tree, representing the T1–T6 groups.

The findings was presented in this study indicate that the major conserved biomarkers beyond CDT were exonuclease, phage integrase, putative membrane, and tail-fiber proteins. Furthermore, with signature proteins of a targeted group, it was shown that phage-related proteins and virulence-associated factors could be commonly transferred by phages. Moreover, in the putative conserved domains of biomarker proteins, phage-related superfamilies were frequently observed. As a result, cdt genes were used as a signature sequences in CDT-producing E. coli strains, and it was shown that they can be used as a powerful biomarker.

In this study, the most significant signature proteins in the five E. coli strains were identified using in-silico whole-genome sequences. It was demonstrated that conserved signature proteins were expressed in a wide range of pathogenic bacterial strains, which could be used in future studies in a broad range of research applications and in modern vaccine-design strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by the Pasteur Institute of Iran. We would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including six tables can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-15-69-s001.pdf.

Supplementary Table 1

Signature details based on Escherichia coli 53638 reference

Supplementary Table 2

Signature details based on Escherichia coli IHE3034 reference

Supplementary Table 3

Signature details based on Escherichia coli RN587/1 reference

Supplementary Table 4

Signature details based on Escherichia coli STEC_B2F1 reference

Supplementary Table 5

Signature details based on Escherichia coli STEC_C165_02 reference

Supplementary Table 6

Aalphabetic abbreviation and description of putative conserved domains