Survey of the Applications of NGS to Whole-Genome Sequencing and Expression Profiling

Article information

Abstract

Recently, the technologies of DNA sequence variation and gene expression profiling have been used widely as approaches in the expertise of genome biology and genetics. The application to genome study has been particularly developed with the introduction of the next-generation DNA sequencer (NGS) Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa systems, along with bioinformation analysis technologies of whole-genome de novo assembly, expression profiling, DNA variation discovery, and genotyping. Both massive whole-genome shotgun paired-end sequencing and mate paired-end sequencing data are important steps for constructing de novo assembly of novel genome sequencing data. It is necessary to have DNA sequence information from a multiplatform NGS with at least 2× and 30× depth sequence of genome coverage using Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa, respectively, for effective an way of de novo assembly. Massive short-length reading data from the Illumina/Solexa system is enough to discover DNA variation, resulting in reducing the cost of DNA sequencing. Whole-genome expression profile data are useful to approach genome system biology with quantification of expressed RNAs from a whole-genome transcriptome, depending on the tissue samples. The hybrid mRNA sequences from Rohce/454 and Illumina/Solexa are more powerful to find novel genes through de novo assembly in any whole-genome sequenced species. The 20× and 50× coverage of the estimated transcriptome sequences using Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa, respectively, is effective to create novel expressed reference sequences. However, only an average 30× coverage of a transcriptome with short read sequences of Illumina/Solexa is enough to check expression quantification, compared to the reference expressed sequence tag sequence.

Introduction

Scientists have tried to understand biology through DNA sequence information, since the DNA is verified as the unit of genetic heredity. Also, scientists hope to dramatically reduce the cost of reading genomic DNA and to obtain the high-throughput DNA sequence information. Since the automated DNA sequencers were developed with fluorescent dyes of different colors, laser, and computer technology in the 1980s, the human genome project (HGP) was begun in 1990, and the human genome was completely released in 2003, while further analysis is still being published. A total of about 3 billion dollars was invested to the project. In 1991, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) funds were geared toward lowering the cost of DNA sequencing. Some of technologies invested improved the DNA sequencing. To date, the Applied Biosystems, Roche/454, and Illumina/Solexa have successfully developed their technology and applied DNA sequencing in the world during the recent 6 years. Most of the newest technologies currently in use generate sequences from 36 to 1,000 base pairs, which requires special software for different applications, including whole-genome sequencing, transcriptome analysis, and regulatory gene analysis. In particular, in silico method development using bioinformation software for next-generation sequence assembly would be alert for many genome projects and more applications in genome biology. Particularly, many biologists and geneticists using massive DNA and RNA sequences have used the sequencing applications focused on the variable research fields in medicine, such as improved diagnosis of disease; gene therapy; control systems for drugs, including pharmacogenomics "custom drugs;" evolution; bioenergy and environmental applications of creative energy sources (biofuels); clean up of toxic wastes, including efficient environmental sources against carbon; and agriculture projects, including livestock of healthier, more productive, disease-resistant farm animals and breeding of disease-, insect-, and drought-resistant crops. In this paper, we report several ways of genome sequencing and expression profiling in genome biology.

Current Next-generation Sequencing (NGS) Technology

Roche/454 pyrosequencing technology

The first high-parallel sequencing system was developed with an emulsion PCR method for DNA amplification and an instrument for sequencing by synthesis using a pyrosequencing protocol optimized on the individual well of a PicoTiterPlate (PTP) [1]. The DNA sequencing protocol, including sample preparation, is supplied for a user to follow the method, which is developed by 454 Life Science (now part of Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Even following the manufacturer's protocol, to obtain high-quality DNA sequence with maximal total DNA sequence length as possible, one should make a library with both adapters on the sheared DNA fragment and mix the optical ratio of library DNA versus bead for emulsion PCR. Now, the system is upgraded to through-put a total of an average of 700 Mbp with an average 600 bp/read in one PTP run. The sequencer is available for single reads and paired-end read sequencing for the application of eukaryotic and prokaryotic whole-genome sequencing [2, 3], metagenomics and microbial diversity [4, 5], and genetic variation detection for comparative genomics [6].

Illumina/Solexa technology

The numerous cost-effective technologies were being developed for human genome resequencing that can be aligned to the reference sequence [7, 8]. The first successful technology to gain massive DNA sequencing available for resequencing was developed by Solexa (now part of Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The principle of the system is the method of base-by-base sequencing by synthesis, where the sheared template DNA is amplified on the flat surface slide (flow cell) and detects one base on each template per cycle with four base-specific, fluorescently labeled signals. Signals for all four fluorescent channels are collected and plotted at each position, enabling quality per scores to be derived using four-color information if desired [8]. Now, a maximum of 300 Gb for reading is available with 101 bp paired-end reading per fragment on a 1-flow cell run in the upgraded HiSeq system.

Application of NGS to Genome Research

Novel whole genome de novo assembly

More than 11,000 sequencing projects, including targeted projects, were reported on the Genome Online Database (GOLD, http://www.genomesonline.org) in early 2012. Now, more than 3,000 genome projects have been completed on the diverse genome species, and more than 90% of completed projects were bacterial genome sequencing. The greatest bacterial genome sequencing was performed with 454 pyrosequencing because of the available largest long read sequencing, useful for de novo assembly of novel genome sequencing. The official depth of the deep sequencing strategy of 454 pyrosequencing technology for whole bacterial genome sequencing for de novo assembly in novel genome sequencing is at least 15-20× in depth of the estimated genome size [9-13]. However, Li et al. [3] reported that 6-10× sequencing in qualified runs with 500-bp reads would be enough for de novo assemblies from 1,480 prokaryote genomes with >98% genome coverage, <100 contigs with N50, and size >100 kb. Recently, prokaryote whole genome sequencing using 101 bp paired-end read data from Illumina/Solexa systems was used for de novo assembly and resequencing. For example, a Bacillus subtilis subspecies genome sequence was generated by using the short read sequence from Illumina/Solexa and assembled with the Velvet program [14]. In this case, the genome assembly was completed, based on the reference genome for ordering the numerous contigs derived from de novo assembly. Even though numerous contigs assembled with Illumina/Solexa data were produced in the eukaryotic genome, a few drafts for the assembled genome sequence were reported, except for the giant panda genome [15], which was covered with assembled contigs (2.25 Gb), covering approximately 94% of the expected whole genome. Another example was the woodland strawberry genome (240 Mb) [16] that was sequenced to 39× depth of the genome, assembled de novo, and anchored to the linkage map of seven pseudochromosomes.

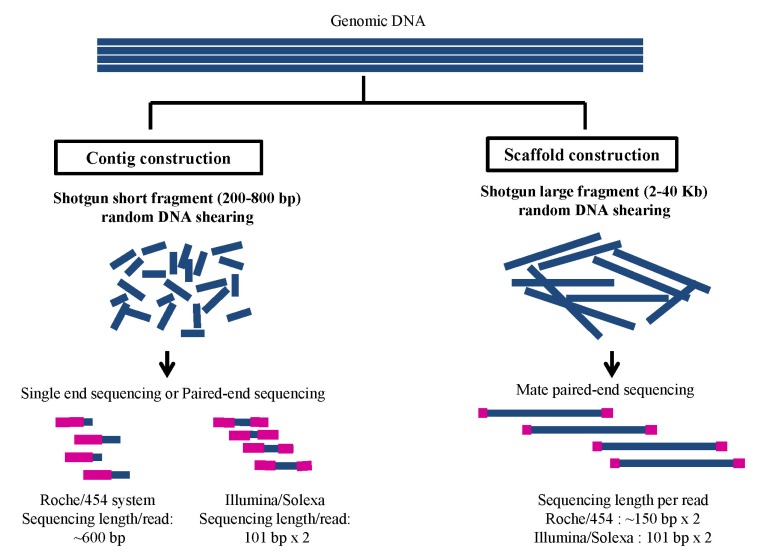

The genome sequence could be associated with the predicted genes with transcriptome sequence data. An ideal method for cost-effective novel genome sequencing using NGS is de novo assembly with diverse shotgun fragment end sequencing data of multiplat systems (Fig. 1). The first strategy of novel genome DNA sequencing is sequencing the genomic DNA for contig and scaffold construction after randomly sheared shotgun single read-end or paired-end read DNA sequencing using Roche/454 or Illumina/Solexa with information on how to assemble with the NGS data using variable assembly software. Recently, a catfish genome was sequenced with multiplatform Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa technology and assembled with an effective combination of low coverage depth of 18× Roche/454 and 70× Illumina/Solexa data using 3 assembly softwares - Newbler software to the 454 reads, Velvet assembler to the Illumina read, and MIRA assembler for final assembly of contigs and singletons derived from initial assembled data - resulting in 193 contigs with an N50 value of 13,123 bp [2]. In an additional multiplatform data assembly of a 40-Mb eukaryotic genome of the fungus Sordaria macrospra, a combination sequence of 85-fold coverage of Illumina/Solexa and 10-fold coverage by Roche/454 sequencing was assembled to a 40-Mb draft version (N50 of 117 kb) with the Velvet assembler as a reference of a model organism for fungal morphogenesis [17]. In the recent effective assembly methods reported, combinations of the multiplatform sequence are shown as successful novel genome assembly using variable assembly strategy pipelines. Comparing the pipeline of assembly strategy, we suggest an effective integrated pipeline in which data are filtered to remove low-quality and short-read initial assemblies using variable software and then compared to contigs, hybrid contigs using MIRA assembler, and finally contig orders using SSPACE software (http://www.baseclear.com/dna-sequencing/data-analysis/) [18] for scaffold construction through de novo assembly of novel genome sequencing (Fig. 2). According to the comparison of several ways of de novo assembly, we suggest using both DNA sequences from multiplatform NGS with at least 2× and 30× depth sequences of genome coverage using Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa, respectively, and doing hybrid assembly for cost-effective novel genome sequencing.

Stringency of whole-genome DNA shotgun sequencing for novel genome. Whole-genome shotgun sequencing (left of the Figure) for contig construction: Sequencing of single-end or paired-end fragment of whole-genome DNA shotgun library, which are made with the average range of 200-800-bp fragments for Roche/454 or Illumina/Solexa systems. In general, producing a total DNA sequence amount of 15-20× and 60× coverage in depth of a genome depends on using Roche/454 or Illumina/Solexa, respectively. Whole-genome shotgun mate paired-end sequencing for scaffold construction (right of the Figure): sequencing of the mate paired-end fragments of the whole-genome DNA shotgun library, which are made with the average range of 2-40-Kb fragments for next-generation DNA sequencer. The sequencing amount of more than 20× coverage in depth of the genome is effective for scaffold constructions.

Integrated pipeline for de novo assembly of novel genome sequencing. The scheme is filtering data to remove low-quality and shot-read initial assemblies using variable software and compare to contigs, hybrid contigs using MIRA assembler, and contig ordering using SSPACE software to scaffold construction.

SNP discovery and genotyping with resequencing

Resequencing of genomic regions or target genes of interest in a phenotype is the first step in the detection of DNA variations associated with the gene regulation. The discovery of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) including insertion/deletions (indels), with high-throughput data is useful to study genetic variation, comparative genomics, linkage map, and genomic selection for breeding value with DNA variation. Many geneticists for biological and genome studies of microbial, plant, animal, and human genomes have effectively used NGS whole-genome resequencing data to use in variable research fields, such as bacterial evolution [19], genomewide analysis of mutagenesis of Escherichia coli strains [20], comparative genomics of Streptococcus suis of swine pathogen [21], genomic variation effects on phenotype and gene regulation in mouse [22], evolution of plant [23], and comparison of genetic variations on the targeted enrichment [24]. The platforms of resequencing projects have used Illumina/Solexa of short read lengths to align with the reference sequence to discover DNA variations between compared related species' sequences. Because of rare occurrence of SNPs in most species, it is important to identify high-accuracy data to discover DNA variations according to coverage depth using MAQ (http://maq.sourceforge.net/maq-man.shtml) [25] and CLC software (http://www.clcbio.com). The public protocol of covering depth to discover SNPs and indels on the heterogeneous genome requires at least 30× of the reference genome, while about 10× depth of coverage is enough for DNA variation study of homogeneous genomes. Of course, high coverage of depth provides high-quality data in SNP detection on the reference mapping (Fig. 3). However, short read lengths of 35 bp or 100 bp show enough to map on the reference sequence using the MAQ software and CLC software in the genome, including short repeated block regions. But, geneticists still require long-read sequencing data to distinguish repeated block regions, like paralogous regions derived from gene duplication. MAQ software provides a consensus sequence of the genotype sequenced of short read lengths with aligned raw reads to the reference sequence. CLC software checks accuracy by counting reads of DNA variations of each position. Recently, a novel application of pattern recognition for accurate DNA variations was discovered in the complexity of the genomic region using high-throughput data in a Caucasian population [26]. They used three independent datasets with Sanger sequencing and Affymetrix and Illumina microarrays to validate SNPs and indels of a clinical target region, FKBP5. Therefore, it is necessary for multiplatform systems to validate DNA variations in the specific complexity of the genome region.

View of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) discovery through mapping short reads from Illumina/Solexa to reference sequence on MAQ software (A) and CLC software (B). (A) Short read 35 bp per read of soybean genome shows completely mapped on the soybean reference sequence. The MAQ software provides a consensus sequence of the genotype sequenced of short read lengths with aligned raw reads to the reference sequence. (B) CLC software is useful for counting reads with DNA variations at each position.

Expression profiling

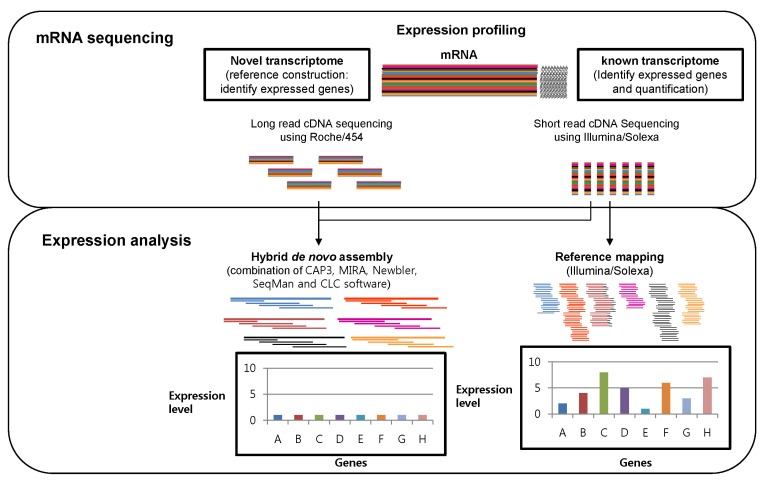

Gene expression profiling is a measurement of the regulation of a transcriptome from the whole genome in the field of molecular biology. A conventional method to measure the relative activity of target genes is DNA microarray technology, which estimates expressed genes with the signals of hybridization of target genes (cDNA from mRNA) on the synthesized oligonucleotides [27]. The technology is still used for functional genomics in the wide era, including medicine, clinic, plant, and agricultural biotechnology [28-30]. In addition, microarray technology is also used in the comparative study of proteomics and expression, measuring the level of extracellular matrix protein [30]. Since NGS technology was developed in 2005, the transcriptome of novel whole genomes could be identified with massive parallel mRNA sequencing using Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa [31-36]. The Roche/454 system is more useful for gaining novel gene discovery of novel species' genomes for long read sequencing [37, 38]. Otherwise, Illumina/Solexa is being used to profile the expression of known genes with mapping short read sequences to the known reference genes [39, 40]. In that case, rare expressed genes and novel genes could be identified with high-throughput expressed sequence tag sequences using Illumina/Solexa. Also, it is useful to find significant tissue-specific expression biases with comparison of transcript data [22]. Now, the hybrid mRNA sequence from Rohce/454 and Illumina/Solexa is more powerful for finding novel genes through de novo assembly in any whole-genome species.

The hybrid sequence data of 20× and 50× coverage of the estimated transcriptome sequence from Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa, respectively, is effective in creating novel expressed reference sequences, while short-read Illumina/Solexa data are cost-efficient on expression quantification information for comparing exposed samples and natural phenotype samples through mapping to the reference genes (Fig. 4). Only and average 30× coverage of transcriptome depth of short-read sequences of Illumina/Solexa is enough to check expression quantification, compared to reference expressed sequence tag sequences. The expressed information could be different, depending on the software using CAP3, MIRA, Newbler, SeqMan, and CLC. Therefore, the results should be compared according to variable program options to define robust expression profiling [41]. To date, a powerful tool of ChIP-on-chip is used for understanding gene transcription regulation. Thus, two-channel microarray technology of a combination of chromatin immunoprecipitation could be used for genomewide mapping of binding sites of DNA-interacting proteins [29]. In any NGS application, the transcriptome expression information would be more useful than complete genome information research with the lowest sequencing budget for biologists to better understand gene regulation of related genetic phenotypes with the in silico method. Of in silico methods, conserved miRNA and novel miRNA discovery is available on the massive miRNAnome data in any species. Specially, the target genes of miRNA discovered could be robust information to approach genome biology studies. Transcriptome assembly is smaller than genome assembly and thus should be more computationally tractable but is often harder, as individual contigs can often have highly variable read coverages. Comparing single assemblers, Newbler 2.5 performed the best on our trial dataset, but other assemblers were closely comparable. Combining different optimal assemblies from different programs, however, gives a more credible final product, and this strategy is recommended [41].

A scheme of transcriptome expression analysis through massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) technology and bioinformatics: The identification of expressed genes through hybrid de novo assembly with Roche/454 and Illumina/Solexa data (left) and expressed level profiling through mapping the Illumina/Solexa sequence to the expressed sequence tag reference.

Conclusion

NGS technology provides a cost-effective way of sequencing for novel whole-genome sequencing, resequencing, and expression profiling. Rohce/454 pyrosequencing is recommended to de novo assembly of whole prokaryote novel genomes, while hybrid assembly with Illumina/Solexa sequences would be optimal for whole eukaryote genomes and transcriptome studies of non-model organisms. Also, Illumina/Solexa sequencing is useful in detecting DNA variation, mapping the short-read resequence to the reference genome and profiling expressed genes in model organisms. Furthermore, the high-throughput NGS sequencing enables us to study with an in silico method in variable research application fields of molecular genetics, including population diversity and comparative genomics, in a short time.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the National Research Foundation (2009-0075946) funded to Ik-Young Choi.