Recent Progress of Genome Study for Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer

Article information

Abstract

Anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) belongs to the most malignant and rapidly progressive human thyroid cancers and its prognosis is very poor. Also, it shows high resistance to cancer treatments, so that effective treatment for ATC has not been found to date, and virtually all patients terminate their life rapidly after diagnosis. Although targeted treatment of genetic alterations has emerged as an extremely promising approach to human cancers, such as BRAF in metastatic melanoma, it remains unclear that how commonly genomic alterations are influenced in ATC tumorigenesis. In recent years, genome wide approaches have been exploited to find genetic alterations associated with complex diseases, including cancer. Here, we reviewed the comprehensive genetic alterations in ATC and recent approaches in the context of identifying genomic alterations associated with ATC. Since surprisingly few reports have been published on the genome wide study of ATC, this review puts emphasis on the urgent needs of genomic research for the prevention and treatment of ATC.

Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the fastest growing cancer worldwide [1]. Especially, in Korea, the average annual incidence rates of thyroid cancer in 2010 was 17.8% recording the highest increasing rate among all cancers (National Cancer Information Center; http://www.cancer.go.kr/). Thyroid carcinomas can be sub-classified according to their histological and clinical features such as cellular origins or prognosis [2]. The most common subtype of thyroid cancers are papillary thyroid cancer (PTC; 80% to 85%) and follicular thyroid cancer (FTC; 10% to 25%), which are differentiated tumors derived from follicular epithelial cells. Poorly differentiated thyroid cancer (PDTC; 5% to 10%) and anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC; 2% to 3%) are also derived from follicular cells. Parafollicular C cell-derived medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) comprises 2-3% of all thyroid cancers [2, 3]. The overall survival rates for PTC (98%), FTC (92%), and MTC (80%) are high [4], and these types have a more favorable prognosis by multimodality treatment. However, ATC has an almost typically rapid and lethal progression, and the survival rate for ATC is only 13% [4] or 1-17% [2] with a mean survival of 6 months after diagnosis [5]. Although ATC supposed to be a follicular-cell-derived cancer, and represents a terminal stage in the dedifferentiation of PTC or FTC [6], the molecular mechanisms underlying ATC are not clear. Because ATC is rare disease, it has been difficult to obtain sufficient samples to study the mechanism of the tumorigenesis associated with ATC which should have great impact to survival and treatment of patients [7]. Here, we reviewed the recent progress of the identification of genetic and epigenetic changes in ATC, focusing especially on genomic study. By this effort, we may clarify the further substances of genomic research to conquer the most aggressive type of thyroid carcinomas.

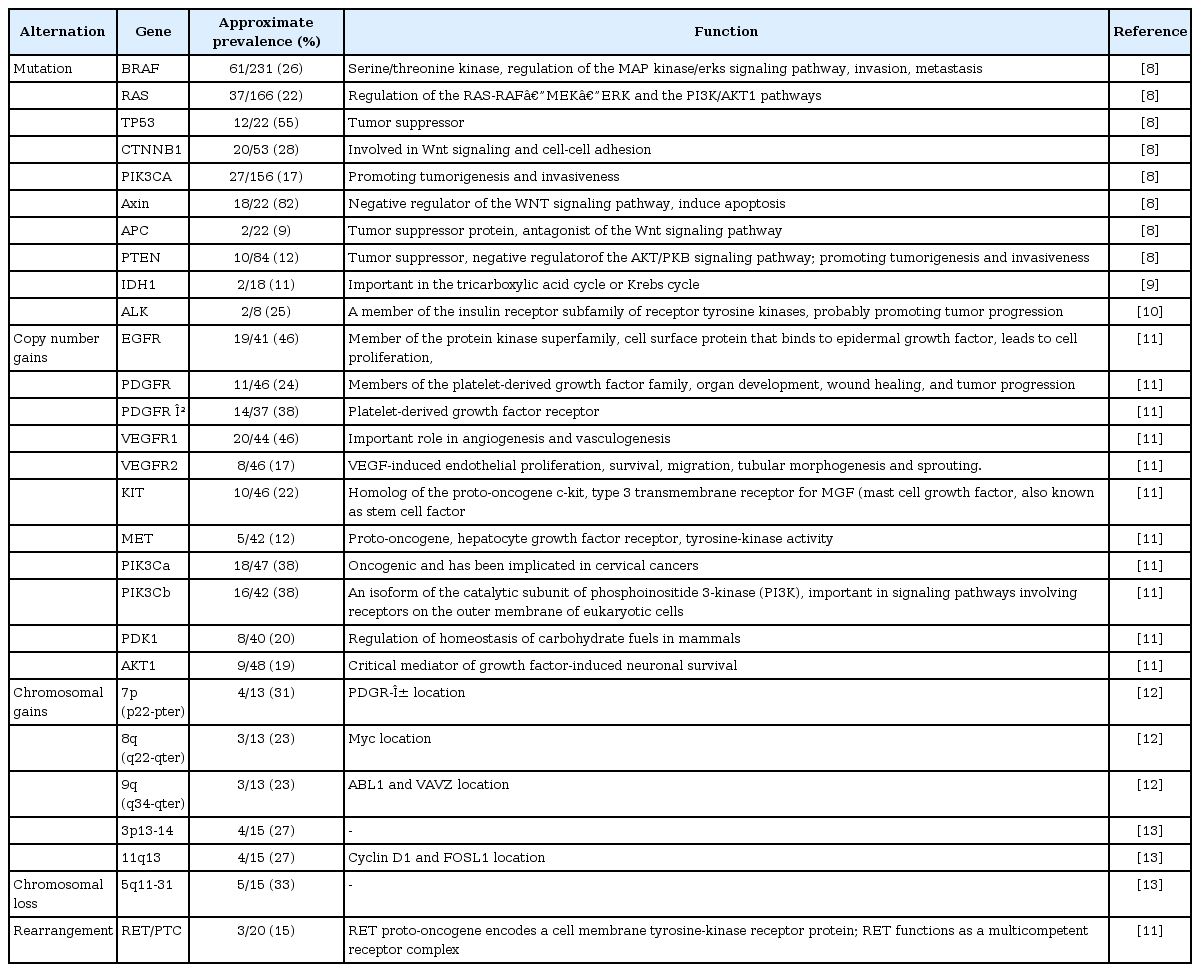

Functional and Frequent Mutations in ATC

To date, a considerable number of genetic mutations have been identified that play roles in the tumorigenesis of ATC, mainly by traditional approaches (Table 1) [8-13]. The most well-known mutation of thyroid cancer is BRAFV600E, occurring in approximately 26% of ATCs and 45% of PTCs [8, 14]. The BRAFV600E mutant protein is produced by the point mutation of T1799A coding sequence, and as consequence the BRAF kinase shows constitutive activity [15-18]. Its oncogenic and transforming capability has been well studies [19] and interestingly, it is strongly associated with poor prognosis of PTC, including aggressive pathological characteristics, increased recurrence rates, and failure of treatment [20, 21].

The tumor suppressor gene p53 is commonly mutated in ATC [8] but uncommon in well-differentiated PTC and FTC. For example, Donghi et al. [22] reported that p53 was mutated in approximately 71% of undifferentiated thyroid cancers (UDTC). Also Fagin et al. [23] reported 83% mutation rate of p53 in ATCs, and Quiros et al. [24] found 88% of p53 mutation in ATC patients using immunohistochemical analysis.

RAS mutations were detected rarely in PTC, but more prevalently in FTC and ATC [25], as if there are relationship between RAS mutations and the aggressiveness of tumor behavior and/or poor prognosis [26, 27]. From three members of RAS family (HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS), codon 12/13 of KRAS mutation is known to be associated with poor survival for more aggressive subtype of thyroid tumors, including ATC [26]. RAS is known as an important regulator of cell growth, differentiation and survival of thyroid cancer [28]. In tumorigenesis, RAS may mediate multiple transduction signaling pathways such as Raf-MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathways [29].

Mutations of PIK3CA are also common in ATC [8]. PIK3CA encodes the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K and PI3K, in turns, involves in the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway, which regulates several cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, adhesion and motility. Especially, this pathway linked to the cell survival, angiogenesis and glucose homeostasis which are important for tumorigenesis [30]. Garcia-Rostan et al. [30] showed that the missense mutations of PIK3CA are higher in ATC than in others such as well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Additionally, ATC patients who had mutated PIK3CA showed also Ras or BRAF alterations.

Garcia-Rostan et al. [31, 32] demonstrated the significant association of mutations in β-catenin and the change of its expression with poor prognosis of ATC. They found that activating mutations of CTNNB1, β-catenin encoding gene, often cause the activation of WNT-β-catenin signaling. In general, as an ubiquitously expressed cytoplasmic protein, β-catenin is a downstream signaling molecule in Wnt pathway, and known to have a crucial role in cell-cell adhesion mediated by E-cadherin. Interestingly, when it is upregulated, the nuclear translocation is occurred so that the transcription of various tumor-promoting genes could be triggered. Axin 1 is a scaffold protein and located in chromosome 16p13.3. It is supposed to be a tumor suppressor and play a role also in the Wnt pathway. Kurihara et al. [33] found the mutation of Axin 1 in 81.8% of 22 Japanese ATC samples. Together, the genetic alterations of genes in the Wnt signaling pathway are found frequently with ATC suggesting the important role of Wnt pathway for ATC tumorigenesis.

Although the mutation prevalence is not high, mutations in the gene for isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) have been recently identified in ATC [9, 34]. The overall prevalence of mutations of IDH1 was reported as 11% in 18 ATC samples by Murugan et al. [9]. Murugan and Xing [10] reported two novel point mutations in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene, C3592T and G3602A, with a prevalence of 25% in 8 ATC tumor samples. ALK, one of the receptor tyrosine kinases, is a member of insulin receptor subfamily and these transverse point mutations caused the amino acid changes L1198F and G1201E, followed by increase of tyrosine kinase activities. Initially, ALK was identified as an oncogeneic fusion gene NPM1-ALK in anaplastic large-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma [35]. Further, fusion gene EML4-ALK was found in non-small-cell lung cancer [36] and TMP3/4-ALK and RANBP2-ALK in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors [37]. They were aberrantly activated and promoted cell proliferation and survival [38, 39].

Although these mutations have been reported to date, it is not clear what of those are the driver mutations of ATC development or if there is any. Also, many other mutations and genes might be associated with ATC tumorigenesis, which may contribute a lot to the diagnosis and treatment of ATC. Therefore, it is a natural consequence that scientists try to adapt genomic approaches to analyze the mechanism of ATC in very recent years.

Chromosomal Aberrations in ATC

Hemmer et al. [12] studied DNA copy number changes by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) in 69 primary thyroid carcinomas including 13 ATC patients. From those 11 ATC cases, showed chromosomal changes (10 gains, 3 deletions, both in 2 cases). Regions of frequent gains were mainly located in 7p22-pter, 8q22-qter, and 9q34-qter regions in 31%, 23% and 23% of ATC cases, respectively. The known proto-oncogenes such as PDGR-α, myc and ABL1, and VAVZ are located, in these regions but still no functional evidences were found supporting the association of copy number changes of these regions and the aggressiveness of ATC. Also, Rodrigues et al. [40] examined 39 thyroid cancer patients including 7 ATCs. All cases of ATC presented chromosomal imbalances, especially, they found gains at chromosome 20p and 20q, and losses of Xp in 6 cases of ATC, and gains at 3q and 5p in 5 cases ATC. Some important genes included PI3K, BCL6, and SST at 3q; invasion and metastases genes (MMP9 and MMP24), a cell cycle and mitotic checkpoint gene (STK15) at 20q. The loss of tumor suppressor gene related 7q31 was detected. The chromosomal instability of ATC revealed as significantly higher than well-differentiated thyroid cancer (WDTC) or PDTC when compared the CGH-detectable abnormalities as reported by couple of studies [12, 40].

Kitamura et al. [41] detected allelic losses using 21 ATC patient samples in 1q (40%), 9p (58%), 11p (33%), 11q (33%), 17p (44%), 17q (43%), 19p (36%), and 22q (38%). Wreesmann et al. [13] reported the unique gains at chromosome 3p13-14 and 11q13 (where the cyclin D1 and FOSL1 located) and losses at 5q11-31 in ATC patients.

Liu et al. [11] found frequent copy number gains in many receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) genes containing the EGFR, PDGFRα, PDGFRβ, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, KIT, MET, PIK3Ca, PIK3Cb, and PDK1 genes. Many of the genes with copy number gains are known to be proto-oncogenes so that they may be play a important role in ATC tumorigenesis by increasing the protein level followed by aberrant activation of the oncogenic pathway. The prevalence of copy number gains was generally higher in ATC than differentiated thyroid cancer [42], also as mentioned in other studies. It is supposed that the copy number variations, which could be occurred by chromosomal amplification or instability, should be important and involved to the progression and aggressiveness of ATC [43].

Chromosomal alteration could cause the genomic rearrangements and fusion genes. In PTC, rearrangement causing RET/PTC fusion gene was observed often, but it rarely occur in benign follicular thyroid adenoma and follicular variant PTC [44]. Liu et al. [11] reported the same RET/PTC rearrangement in 3 cases of ATC tissues, but because some ATC tissues contained PTC tissues, they were suspicious to their result. Therefore, if chromosomal rearrangement and fusion genes, including RET/PTC fusion, involve to the ATC progression, should be investigated further.

Expression Analysis in ATC by Microarray

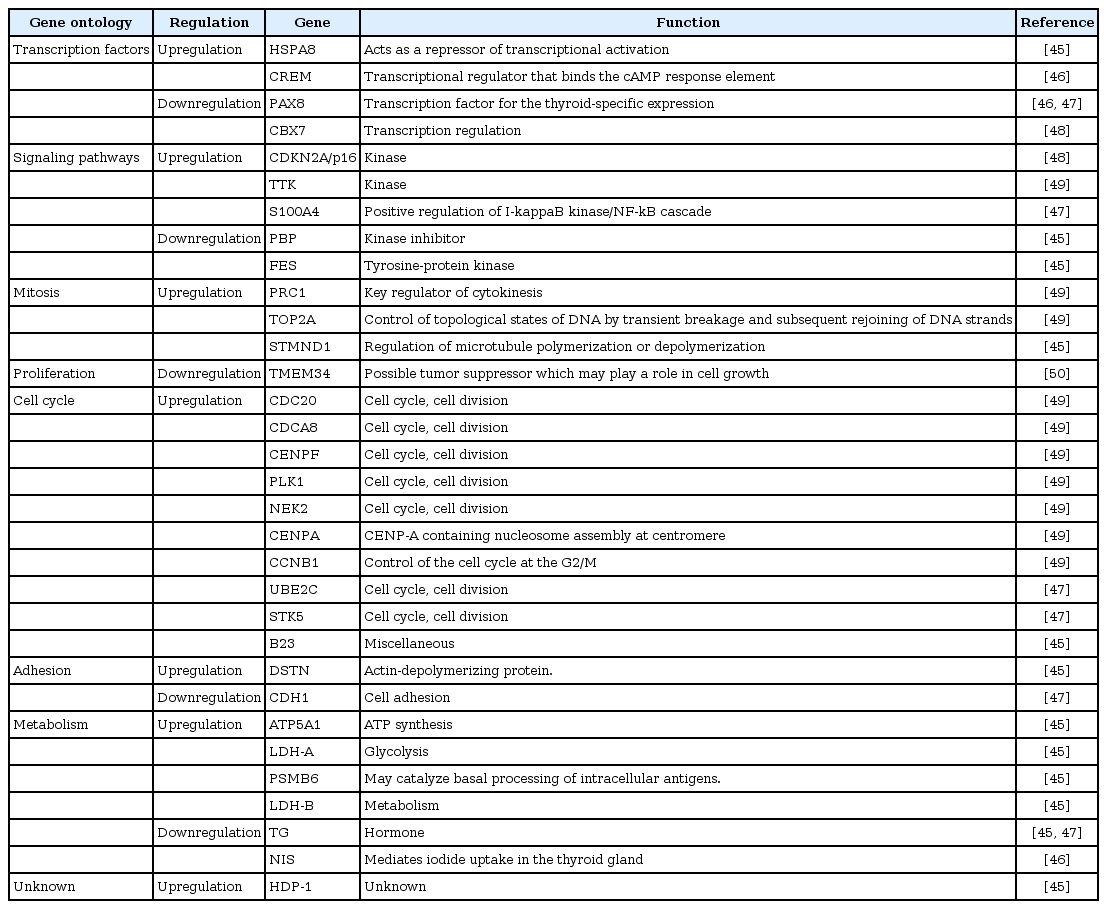

Although not many investigations for genome wide expression analysis were performed, several studies examined altered expression of genes in ATC cell lines or patient samples using microarray (Table 2) [45-50]. The upand downregulated genes in ATC identified as players in the regulation of important cellular functions which may influencing to the tumorigenesis. Onda et al. [45] found 31 over- and 56 under-expressed genes using 11 ATC cell lines compared with normal thyroid gland; then they validated these data with 10 ATC patient samples, among them, DSTN, HSPA8, Stathmin, LDH-A, ATP5A1, PSM B6, B23, HDP-1, and LDH-B were significantly upregulated in primary ATC patient samples. On the other hand, TG, PBP, and FES were downregulated in primary ATC tissues compared with normal thyroid glands. In other study of ATC cell lines, Akaishi et al. [50] identified transmembrane protein 34 (TMEM34) as specifically downregulated gene.

Although it is not a microarray analysis, Passon et al. [46] measured mRNA levels for CREM, PAX8, and NIS in 6 normal thyroid tissues, 22 PTCs, 12 FTCs, and 4 ATCs using quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis. Compared to normal tissues, NIS and PAX8 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in all types of thyroid cancer, especially in ATCs. Conversely, CREM mRNA levels were increased in all types of thyroid cancer including ATC.

To find molecular profile related to poor prognosis of thyroid cancer, Montero-Conde et al. [47] examined 7 ATC, 6 PDTC, 24 PTC and 7 FTC tissues by microarray. They comprised 13 dedifferentiated thyroid cancer (ATC and PDTC) vs. 31 WDTC (PTC and FTC) tissues. In this data, they found that 1,031 genes showed more than 2-fold changes of its expression in absolute values. Interestingly, pathways which are known to associated with tumorigenesis were preferentially altered in ATC and PDTC tissues; the MAP kinase signaling pathway, the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway, focal adhesion and cell motility, activation of actin polymerization, and cell cycle. UBE2C, S100A4, and STK5 were significantly overexpressed in ATC and PDTC than WDTC. CDH1, TG, and PAX8 were significantly underexpressed in ATC and PDTC than WDTC, of those the down regulation of TG and PAX8 were also reported by Onda et al. [45] and Passon et al. [46].

In other study, Pallante et al. [48], reported downregulation of CBX7 expression using microarray analysis in various thyroid carcinoma-derived cell lines. Then, they validated this finding in various thyroid tissue samples. They show that CBX7 expression decreased with malignancy grade cancer tissues than in normal tissues. Interestingly, in same study, CBX7 loss of heterozygosity occurred in 36.8% (7 of 19 cases) of PTCs and in 68.7% (11 of 16 cases) of ATCs. mRNA for CDKN2A/p16 which is the molecular target of CBX7 and known to be a tumor suppressor, was also highly expressed.

As direct study of patient samples, Salvatore et al. [49] did a microarray analysis using 5 ATC compared with 10 PTC and 4 normal thyroid tissue and validated their data with further 22 ATC, 39 PTC and 19 normal thyroid samples. 914 genes distinguished ATC from normal tissue: and only 114 genes were found to discriminated normal thyroid from both PTC and ATC. Especially, 54 genes were upregulated in ATC and they are largely involved in cell cycle progression or chromosome instability. Among them, TOP2A, CDC20, CENPA, NEK2, PRC1, CCNB1, CDCA8, TTK, CENPF, and PLK1 expression was ATC-specifically up-regulated.

Taken together, the previous studies of genomic expression analysis suggested some of interesting genes and molecular changes using microarray, they could not find clearly the major driver genes or pathways for ATC tumorigenesis. This may be due to the hardness of sample collection or ATC itself could have a very complex heterogeneity. But the technical limitation of microarray itself may contribute also largely. The recently applicable next generation sequencing technology could help to solve this issue so that the molecular contribution of gene expression changes for ATC could be resolved.

Epigenetic Alterations in ATC

Since the epigenetic changes of tumor-associated genes are known to play important role and have physiological function in the development of various human cancers and its progression [51, 52], they may also influence to the tumorigenesis of the most malignant form of thyroid cancer, ATC. In PTC cells, genome-wide hypermethylation was found by a recent study using DNA methylation microarray which is revealed to be driven by BRAFV600E signaling [53]. Other couple of papers focused more to the change of methylation pattern in ATC. Schagdarsurengin et al. [54] analyzed the methylation pattern of 17 gene promoters in ATC, included those involved in DNA damage avoidance and repair (MGMT, GSTP1), apoptosis (DAPK, UCHL1), cell cycle control (p16, RB), tumor invasion and metastasis (TIMP3, CD26), hormone response (RARβ, ERα, ERβ), signal transduction (PTEN, RASSF1A), regulation of thyrocyte function and growth (TSHR), and other tumor-associated genes (DLC1, SLC5A8). Among these genes, they found that TSHR, MGMT, UCHL1, p16, and DAPK were frequently methylated in ATC.

PTEN, as a well-established tumor suppressor, is involved in the PI3K/AKT pathway. Hou et al. [55] found that PTEN methylation is necessary to progress the malignancy from benign thyroid adenoma to FTC and aggressive ATC. The methylation of a gene is usually associated with its silencing and the increased methylation of PTEN in ATC is in concordance with decreased or even lack of PTEN expression in previous reports [56, 57]. They also found that PTEN methylation in thyroid tumors was closely associated with the activating genetic alterations in the PI3K/Akt pathway, including mutations in Ras, PIK3CA, PTEN gene and PIK3CA amplification [55].

Four microRNAs (miRs) (-30d, -125b, -26a, and 30a-5p) were reported by Visone et al. [58] as decreased in ATC compared with normal thyroid tissue. From these, miR-26a and -125b may be targeting HMGA1 and HMGA2 which are known to be involved in thyroid cell transformation [59]. In other report by Mitomo et al. [60], found the upregulation of miRs-21, -146b, -221, and -222 and downregulation of -26a, -138, -219, and -345 in thyroid cancer. From these, miR-21 targets E2F (involved in cell cycle and apoptosis) and inhibits PTEN. Interestingly, miR-138 which was found to be downregulated in both study of Visonet's and Mitomo's group [58, 60], targets hTERT which is also found to be reduced. Takakura et al. [61] identified ATC specifically deregulated miRNAs in ATC cell line. They found that overexpression of miR-17-92 cluster of 7 miRNAs (miR-17-3p, -17-5p, -18a, -19a, -19b, -20a, and -92-1), which has a crucial role in cell growth and survival. Additionally, miR-17-3p and -17-5p 5p were overexpressed in 3 out of the 6 ATC patient samples.

Conclusion

Although ATC is known to be one of the most aggressive tumor types, there has been little progress in the diagnosis and treatment, largely due to the shortage of genetic information associated with the molecular mechanism of ATC tumorigenesis. In this review, we discussed genetic alterations, structural variations, and epigenetic changes of ATC performed by many scientists to date. As shown, only limited information is available, and few studies were performed using genome-based approaches. Generally, the quantities and qualities of samples for genomic study are very high, so that it is not easy to fulfill the requirements. Therefore, collecting a sufficient number of samples for ATC matching these criteria is a kind of challenge for many scientists. However, current next-generation sequencing techniques require smaller amounts of samples and are applicable for less-qualified samples but provide more accurate results for researchers to evaluate diverse genetic alterations.

Recently, the technical advances of genome study developed explosively so that it could provide more comprehensive information on cancer genomics, especially for gene expression, sequence variations, copy number changes, and epigenetic changes [62]. Using such technology such as next generation sequencing and big data, rapid progress has been realized in many parts of cancer molecular biology, which in turn contributes to the development of early diagnosis tools and/or targeted molecular therapies. Thus, less-detailed cancer types have been intensively targeted by current genomic studies. For example, many studies have analyzed the genomic alterations associated with lung cancer and reported detailed molecular events that could be used directly in the clinic, such as selection of the most effective drug for each patient. For thyroid cancer, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has deposited the analysis results of -500 thyroid cancer genomes in their public website, which may be published very soon. These analyses will provide a more detailed, multidimensional genomic characterization of thyroid cancer genomes. However, most of the 500 thyroid cancer genomes in TCGA were only from PTC patients, and none was from an ATC patient.

It is clear that genomic study of ATC is urgently needed so that the molecular mechanisms of ATC and the genetic and epigenetic changes in ATC could be more preciously understand. Studies on ATC-associated genetic alterations, such as mutations and aberrant structural and epigenetic changes, based on genomic approaches should help to elucidate the molecular consequences of the activation of oncogenes and the loss of tumor suppressors to improve our understanding of tumor biology in ATC. Especially, using recently developmed NGS technology, we will get a deep understanding of ATC-specific molecular mechanisms for successful diagnosis and treatment of this aggressive cancerand further facilitate the search for prognostic and predictive markers and new therapeutic targets for personalized medicine.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Intramural Research Grants of the National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC 1210340).