Characterization of H460R, a Radioresistant Human Lung Cancer Cell Line, and Involvement of Syntrophin Beta 2 (SNTB2) in Radioresistance

Article information

Abstract

A radioresistant cell line was established by fractionated ionizing radiation (IR) and assessed by a clonogenic assay, flow cytometry, and Western blot analysis, as well as zymography and a wound healing assay. Microarray was performed to profile global expression and to search for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to IR. H460R cells demonstrated increased cell scattering and acidic vesicular organelles compared with parental cells. Concomitantly, H460R cells showed characteristics of increased migration and matrix metalloproteinase activity. In addition, H460R cells were resistant to IR, exhibiting reduced expression levels of ionizing responsive proteins (p-p53 and γ-H2AX); apoptosis-related molecules, such as cleaved poly(ADP ribose) polymerase; and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related molecules, such as glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) and C/EBP-homologous protein compared with parental cells, whereas the expression of anti-apoptotic X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein was increased. Among DEGs, syntrophin beta 2 (SNTB2) significantly increased in H460R cells in response to IR. Knockdown of SNTB2 by siRNA was more sensitive than the control after IR exposure in H460, H460R, and H1299 cells. Our study suggests that H460R cells have differential properties, including cell morphology, potential for metastasis, and resistance to IR, compared with parental cells. In addition, SNTB2 may play an important role in radioresistance. H460R cells could be helpful in in vitro systems for elucidating the molecular mechanisms of and discovering drugs to overcome radioresistance in lung cancer therapy.

Introduction

Lung cancer, the most common cause of cancer-related death in men and women, is responsible for 1.38 million deaths annually, as of 2008 [1]. The main types of lung cancer are small-cell lung cancer (approximately 19%) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC; around 80%). Although NSCLC is sometimes treated with surgery, advanced and metastatic NSCLC usually responds better to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (RT) [2]. RT, either alone or in combination with surgery or chemotherapy, plays a major part in NSCLC management. Tumor radioresistance may greatly reduce the efficiency of RT for NSCLC [3]. RT of a primary tumor accelerates metastatic growth in mice [4]. These invasive and metastatic mechanisms are associated with the recruitment of complex and numerous classes of proteins, including cadherins. Specifically, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play a key role in the degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Augmented MMP expression and its activity are associated with advanced tumor stage and poor survival. Elevated plasma levels of MMP-9 have been found in lung, breast, and liver cancers during RT [5, 6]. In addition, MMP-9 from sublethally irradiated tumors promotes Lewis lung carcinoma cell invasiveness and pulmonary metastasis [7]. Recently, MMP inhibitors were shown to block radiation-induced invasiveness of human pancreatic cancer cells [8]. In addition, expression of β-catenin plays a pivotal role in maintaining the integrity of cellular functions [9].

Ionizing radiation (IR)-induced double-strand DNA breaks ead to activation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM), which responds through autophosphorylation and activation of DNA repair pathways, including phosphorylation of histone H2AX (γ-H2AX), a signal for recruitment of molecular DNA repair complexes. In addition to a role in DNA damage repair, H2AX is required for DNA fragmentation during apoptosis and is phosphorylated by various kinases in response to apoptotic signals. ATM stimulates IR-induced cycle arrest through activation of checkpoint kinases; p53; and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, such as p21 [10]. Moreover, poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in DNA repair in response to environmental stress [11], helps cells maintain their viability, and cleavage of PARP serves as a marker of cells undergoing apoptosis [12]. IR also induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress via upregulation of GRP78 and GRP94 in rat intestinal epithelial cells [13]. The level of C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) expression is elevated during ER stress, and CHOP-deficient cells have enhanced survival when challenged with toxins that induce ER stress, suggesting that CHOP functions to mediate programmed cell death [14].

Syntrophins are intracellular peripheral membrane proteins of 58-60 kD, originally identified as proteins enriched at the postsynaptic apparatus [15]. The three syntrophin isoforms, α1, β1, and β2, are encoded by different genes but have similar domain organizations [16]. Syntrophins consist of a C-terminal syntrophin unique domain and an N-terminal pleckstrin homology domain, split by insertion of a PDZ domain. Although syntrophins have been recognized as an important component of many signaling events, such as insulin secretion, synapse signaling, and migration regulation [17-21], little is known about the involvement of syntrophin beta 2 (SNTB2) in radioresistance.

In the present study, we established radioresistant NSCLC H460R cells. We tried to analyze these cells in response to IR to identify SNTB2 among upregulated genes in radioresistant H460R cells and to provide new insights into the involvement of SNTB2 in radioresistance.

Methods

Cell culture

Human NSCLC cell lines (ATCC, Bethesda, MD) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Welgene, Daegu, Korea), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen), at 37℃ under an atmosphere containing air and 5% CO2. Cell morphology was observed under an inverted light microscope.

Establishment of radiation-resistant H460R cells

H460 cells were seeded in 100-mm culture dishes and irradiated with 2 Gy γ-rays using a Gammacell 3000 (Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd., Chalk River, ON, Canada) at a dose rate of 3.2 Gy/min when cells approached 60% confluence. When the cells reached about 90% confluence, they were subcultured into new culture dishes. The cells were treated again with 2 Gy γ-rays at about 60% confluence. These procedures were repeated over a period of 24 months. The parental cells were cultured under the same conditions without ionizing irradiation.

Acridine orange staining

Acidic vesicular organelles were quantified by vital staining with Acridine Orange (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Both the cytoplasm and nucleolus fluoresced bright green and dim red, whereas acidic compartments fluoresced bright red. The intensity of red fluorescence is proportional to the degree of acidity and/or the volume of the cellular acidic compartment [22]. Cells were stained with acridine orange and analyzed by flow cytometry and Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

MTT assay and Trypan Blue staining

For the MTT assay, cells were seeded at a density of 1,000 cells per well on 96-well plates, and 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide reagent (Sigma) was added to each well. After incubation for 4 h at 37℃ in an incubator under 5% CO2, dimethyl sulfoxide was added, and absorption was measured at a wavelength of 595 nm. Viable cells were identified based on their ability to exclude the dye via Trypan Blue (Invitrogen) staining.

Cell cycle analysis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurement

Cells were fixed with 75% cold ethanol and stained with a solution containing propidium iodide and RNase A (Sigma). For ROS measurement, cells were stained with 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), and the fluorescence of 10,000 cells was measured by flow cytometry.

Clonogenic assay

Colonies were fixed in methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet. Colonies 1.0 mm in diameter were counted, and average colony numbers were multiplied by the dilution factor of the cell number. Each value at every dose was divided by the control value for the survival fraction.

Gelatin zymography

Conditioned media were separated with the use of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) containing 0.2% gelatin. The gel was renatured with 2.5% Triton X-100 buffer for 1 h and incubated with developing solution (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM CaCl2) for 18-20 h at 37℃. The gel was then stained with 0.5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Sigma) in 30% methanol and 10% glacial acetic acid and destained with the same solution without dye.

Wound healing assay

Cells were seeded on a 24-well plate, and a wound was generated using a 200-µL tip; medium containing 10% FBS was added. Wound healing was observed under a microscope after 0, 16, 24, and 48 h. Images were captured and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Western blot analysis

Cells were dissolved in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 120 mM NaCl) containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. After quantification with Bradford assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), proteins were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and probed with specific antibodies overnight at 4℃. Membranes were developed using a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized by chemiluminescence with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Microarray analysis

Parental and radioresistant cells were irradiated with 4 Gy γ-rays. Cells were harvested after 48 h, and microarray was performed using Affymetrix GeneChip human genome U133 plus 2.0 arrays (ITSTech, Seoul, Korea). Data were normalized via global scaling (GenPlex), and genes over the cutoff of 2 were selected based on values of log2 (fold-change): upregulated genes with 'p < 0.05' for detection value were selected in the H460R array, and downregulated genes with 'p < 0.05' for detection value were selected in the H460 array (ITSTech and Macrogen, Seoul, Korea). Analysis of significant genes was performed by Welch's t-test. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were analyzed between parental and radioresistant cells. Fold-change values in descending order of 200 genes were selected from upregulated genes and downregulated genes. False discovery rate and Bonferroni-corrected p-values were calculated (Macrogen).

SNTB2 knockdown by siRNA

Cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. After overnight culture, each well was transfected with 20-40 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). After 24 h of transfection, the cells were treated with or without IR. The SNTB2 siRNA and negative control siRNA were as follows: SNTB2 (sense: 5'-GUCUCUCUAGGCUGCAUGUdTdT-3', antisense: 5'-ACAUGCAGCCUAGAGAGACdTdT-3') and negative control (sense: 5'-GAUCAUACGUGCGAUCAGAdTdT-3' and antisense: 5'-UCUGAUCGCACGUAUGAUCdTdT-3').

Statistical analyses

Three independent experiments were performed, and the results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses of experimental data were determined using two-sided student's t-test. p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Establishment and cellular morphology of H460R cells

Radioresistance means the relative resistance of cells, tissues, organs, or organisms to the injurious effects of IR. During the treatment period, recovery from radiation damage between fractions has been shown to increase tumor resistance against fractionated RT [3]. Radioresistance in vitro may be induced by exposure to small doses of IR [23]. To generate radiation-resistant cells, H460 cells were seeded in 100-mm culture dishes and irradiated with 2 Gy γ-rays at a dose rate of 3.2 Gy/min when cells approached 60% confluence. When the cells reached about 90% confluence, they were subcultured into new culture dishes. The cells were treated again with 2 Gy γ-rays at about 60% confluence. These procedures were repeated over a period of 24 mo. The parental cells were cultured under the same conditions without ionizing irradiation. These cells were designated H460R and utilized in this study.

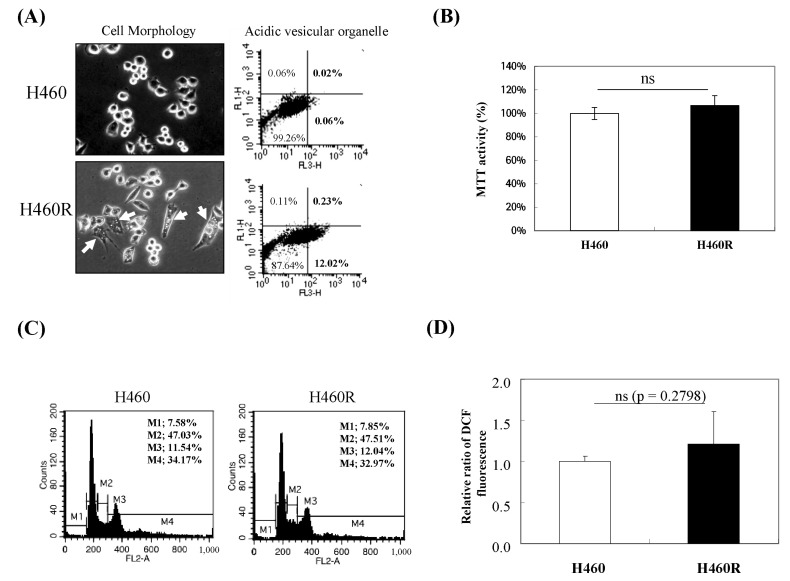

The parental H460 cells typically appeared cobblestone-like and showed tight cell-cell junctions, which is characteristic of the epithelial phenotype. In contrast, H460R cells exhibited a spindle-like morphology and demonstrated a loss of cell-to-cell contact and an increase in cell scattering, as well as acidic vesicular organelles (Figs. 1A and 2A). Since a little difference in proliferative potential, such as cell cycle, has been reported between parental H460 and radioresistant H460R cells [23], we also examined whether established H460R cells are different from the parental H460 cells in cell proliferation, cell cycle, and ROS levels under physiologically normal conditions. Consistent with Lee et al.'s findings [23], no significant differences in cell proliferation, cell cycle, or ROS levels were observed between H460 and H460R cells under physiologically normal conditions (Fig. 1B, 1C, and 1D).

Analysis of radioresistant H460R cells under physiologically normal conditions. (A) Morphology changes and increased vacuoles in H460R cells. Arrow points to a vesicular organelle (left). Flow cytometry after acridine orange staining (right). (B) MTT activity. (C) Cell cycle and (D) reactive oxygen species levels between H460 and H460R cells from flow cytometric analysis. Not significant (ns); p > 0.05 vs. H460 (n = 3). MMP, matrix metalloproteinase.

Migration and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 and MMP9 activities increased in H460R cells. (A) Comparison of colony morphology between H460 and H460R cells. (B, C) Wound healing assay. (D) Zymography (upper) and expression of representative proteins (lower) related to the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition between H460 and H460R cells. **p < 0.01 vs. H460 (n = 3).

Increased migration and MMP2 and MMP9 activity in H460R cells

Since spindle-like morphology and an increase in cell scattering were found in H460R cells (Fig. 1A), a small number of cells were seeded and cultured for 8 days; colonies were stained with crystal violet. We observed scattered morphology of colonies in radioresistant H460R cells compared with parental cells. To test the possibility of increased metastasis in H460R cells, we measured migration and representative MMP activities, including MMP2 and MMP9, using a wound healing assay (Fig. 2B and 2C) and gelatin zymography (Fig. 2D), respectively. We confirmed significantly increased migration as well as MMP2 and MMP9 activities in H460R cells. Since E-cadherin and N-cadherin are known as important marker proteins for the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, expression levels of these proteins were determined via Western blot analysis. E-Cadherin was not detected (data not shown), and no difference was observed in the expression of N-cadherin protein between H460 and H460R cells. However, β-catenin protein levels increased in radioresistant H460R cells (Fig. 2D).

Differential response of H460R cells to γ-irradiation

It has been known that radioresistant cells have some characteristics, such as DNA repair and anti-apoptotic properties, in response to IR as well as other anticancer drugs [23]. Next, we checked the response to IR between parental H460 cells and resistant H460R cells. A colony formation assay indicated that H460R cells were more resistant to cell death than parental cells after 4 and 6 Gy irradiation (Fig. 3A and 3B). In addition, cell cycle analysis showed that H460 cells were subjected to early apoptosis, whereas H460R cells were arrested at the G2/M phase. Subsequently, the subG1 fraction in H460 cells was increased 2-fold over H460R cells after 24 h with IR (Fig. 3C). From these results, we considered H460R cells to be radioresistant. To evaluate the cellular response to IR, levels of proteins with respect to DNA damage and cell cycle were analyzed. IR led to enhanced phosphorylation of p53 in the parental cells compared with H460R cells. While γ-H2AX expression appeared after 8 h and peaked 32 h after IR in parental cells, it was only slightly induced in radioresistant H460R cells. Moreover, p21, p27, and cyclin B1 remained increased in response to IR in H460R cells. We also observed that the cleaved form of PARP increased in H460 cells after 8 h and peaked after 32 h, whereas a slight increase of cleaved PARP was observed in H460R cells (Fig. 3D). X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) expression levels increased in H460R cells but decreased in parental cells after IR exposure. To test whether IR induced upregulation of ER stress in the two cell lines, we performed Western blot analysis for representative marker proteins, such as glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), glucose-regulated protein 94 (GRP94), and CHOP. In parental cells, GRP78 and CHOP increased in a time-dependent manner in response to IR up to 24 h and decreased after 32 h of IR, while expression of GRP94 decreased in a time-dependent manner following IR. Moreover, IR decreased GRP78 but increased GRP94 and CHOP slightly, which were rarely detected, regardless of IR in radioresistant cells (Fig. 3E).

Differential response of H460R cells to γ-irradiation. (A, B) Clonogenic assay. (C) Cell cycle analysis. (D) Western blot of DNA damage response. (E) Analysis of representative proteins related to endoplasmic reticulum stress. *p < 0.05 vs. H460 (n = 3). CTL, control; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis; PARP, poly(ADP ribose) polymerase; CHOP, C/EBP-homologous protein.

Global expression analysis and involvement of SNTB2 in radioresistance

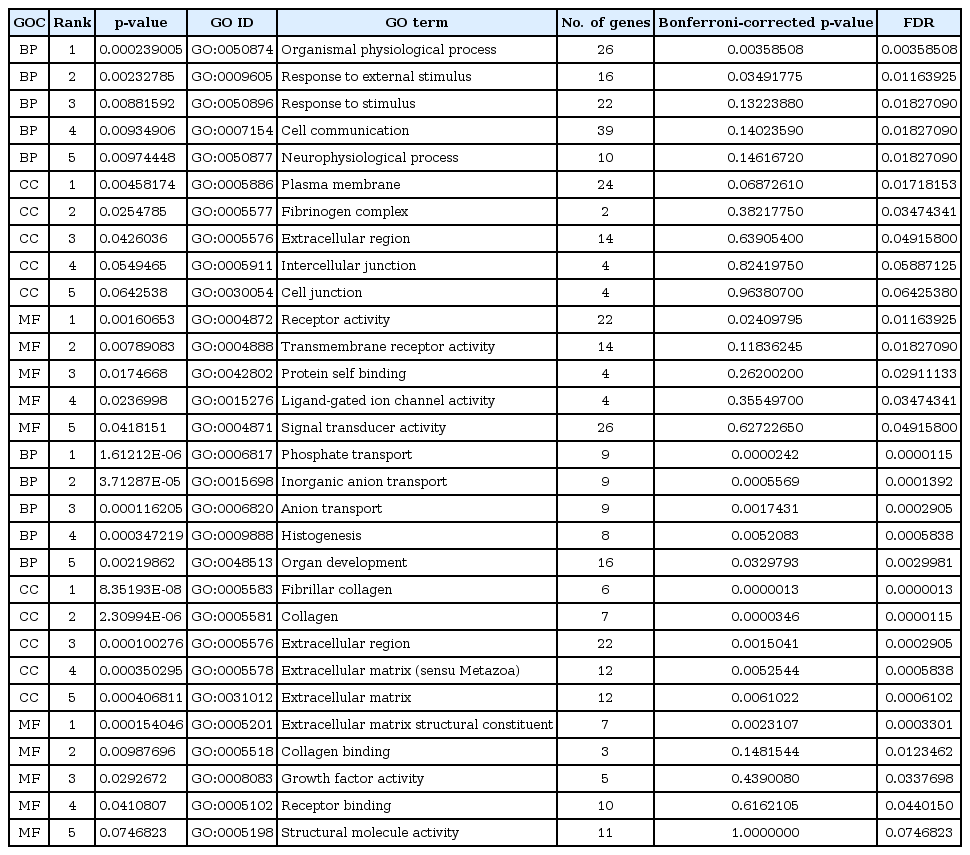

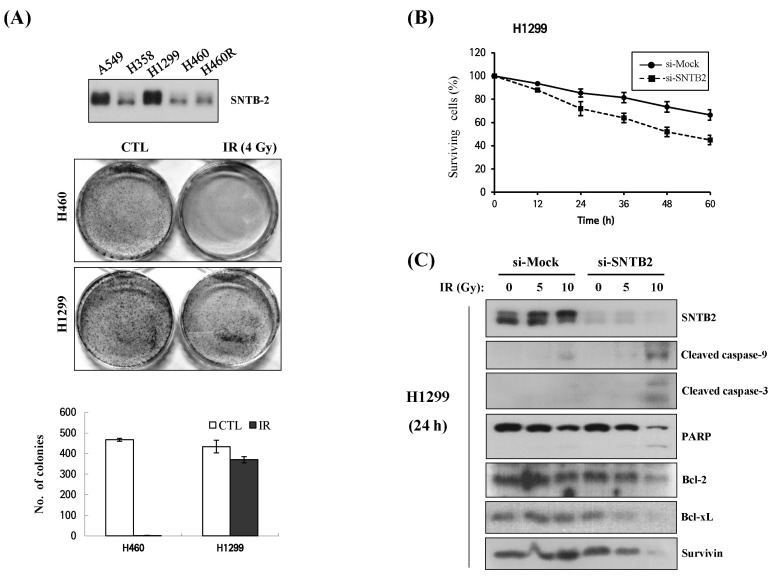

A cDNA microarray was used to analyze DEGs in H460R cells in response to IR. Four hundred genes that were either up-regulated or down-regulated, demonstrating more than 2-fold changes in H460R cells, are categorized in Table 1, which is shown to summarize the enriched gene ontology terms of the selected gene set. Among up-regulated genes in response to IR, we focused on genes listed in the 'plasma membrane' category among the cellular components categories. In addition to being a membrane adapter protein, SNTB2 was modulated by interaction with MRP2 [24], a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein superfamily, functioning as an ATP-dependent export pump for anionic conjugates in the apical membranes of epithelial cells. Since ABC proteins have been implicated in resistance [25, 26], SNTB2 was selected for further analysis to evaluate whether it is involved in radioresistance. Consistent with the microarray data, protein levels of SNTB2 in H460 cells were highly increased in response to IR compared to the parental cells (Fig. 4A). Knockdown of SNTB2 by siRNA sensitized H460R cells as well as the parental cells to IR (Fig. 4B and 4C), although the effect of si-SNTB2 on H460R was less compared with parental cells. SNTB2 expression levels were examined in other NSCLC cell lines to determine whether A549 and H1299 cells expressed high levels of SNTB2 compared with H460 cells and H1299, which are more resistant to IR exposure (Fig. 5A). We verified that knockdown of SNTB2 by siRNA made H1299 cells more sensitive to IR exposure (Fig. 5B and 5C), suggesting that SNTB2 plays a role in radioresistance.

Effects of si-syntrophin beta 2 (SNTB2) on ionizing radiation (IR)-induced apoptosis in H460 and H460R cells. (A) SNTB2 expression, relative ratio of SNTB2 proteins, and poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage in response to IR (4 Gy). After irradiation, Western blot analysis was performed. (B) Effect of SNTB2 knockdown on IR-induced cell viability. After transfection using si-mock or si-SNTB2 siRNA, cells were analyzed by Western blot (upper), and after IR to siRNA-treated cells, cell viability was measured via Trypan Blue exclusion assay (lower). *p < 0.05 vs. si-mock (n = 3). (C) Colony formation assay after IR to siRNA-treated H460 and H460R cells.

Effects of si-syntrophin beta 2 (SNTB2) on ionizing radiation (IR)-induced apoptosis in H2199 cells. (A) Expression level of SNTB2 in non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines (upper) and colony formation assay after IR in H460 and H1299 cells (lower). CTL, control. Effect of SNTB2 knockdown on IR-induced cell viability (B) and IR-induced apoptosis (C) in H1299 cells. After transfection with si-mock or si-SNTB2 into H1299 cells, cells were irradiated, and cell viability was measured by a Trypan Blue exclusion assay; lysates were analyzed by Western blot using cleaved caspase-9/-3, poly(ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP), Bcl-2, and survivin antibodies.

Discussion

Cancer cells often demonstrate resistance to IR, fail to arrest the cell cycle to repair DNA damage, and continue to proliferate under genotoxic stress [10]. Therefore, it is very important to understand radioresistance as well as enhanced invasiveness for RT.

In the present study, we established radioresistant NSCLC H460 cells by fractionated low-dose IR and evaluated their response to IR. Identification of DEGs related to DNA damage, cell growth, and ECM compared with parental cells in radioresistant lung cancer cells that have been developed by fractionated IR has been reported [23, 27]. IR induces autophagy and the formation of acidic vesicular organelles in cancer cells [22]. We also found that H460R cells had a distinct morphology, with enhanced cell scattering and an increase in acidic vesicular organelles. Low-dose IR has been shown to induce changes in the cellular microenvironment, leading to mesenchymal changes, and to significantly enhance the ability of migration and invasion in breast cancer cells [28]. Differentiation pathways have been involved in radioresistance as well as chemoresistance [29]. For example, Wnt/beta-catenin mediates radiation resistance [3, 30]. Some of these genes may be responsible for the emergence of resistance to therapy-for example, MMPs [31]. We also observed that radioresistant H460R cells exhibited increased activities of migration and representative MMPs, including MMP2 and MMP9, compared with parental cells. Our findings are consistent with recent studies showing that MMPs are able to control metastasis [2, 15, 32]. In addition, expression of β-catenin appeared in radioresistant cells but not in parental cells. Based on our observation of rare expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin, β-catenin might play an important role in radioresistant H460R cells. Our findings suggest that H460R cells might have the potential for invasion and metastasis, which will be elucidated in a future study. H460 cells with wild-type p53 responded with a shorter G2/M phase, leading to increased apoptosis compared with radioresistant H460R cells. Results from flow cytometry correlated with a series of Western blot data. Expression levels of XIAP decreased in the parental cells but increased in H460R cells. Expression patterns of GRP78 and GRP94 in H460R cells were different from those of parental cells. Strongly increased CHOP protein levels in H460 cells after 8 h by IR, but not in H460R cells, were consistent with a previous study showing that CHOP-deficient cells have enhanced survival when challenged with toxins that induce ER stress [14]. These data suggest that H460R cells are altered in response to IR-induced ER stress as well as DNA damage.

In this study, SNTB2 increased after IR exposure, and knockdown of SNTB2 led to an increase in sensitivity in both H460 and H460R cells in response to IR. However, the effect of si-SNTB2 on H460R was less compared with the parental cells. H460R cells can be considered to be genetically more heterogeneous in response to repeated IR. In fact, we observed that si-SNTB2 did not sufficiently knock down SNTB2 levels in H460R cells compared with the parental cells, based on data from the Western blot analysis. Hence, we alternatively utilized IR-resistant H1299 cells to confirm that SNTB2 is involved in radioresistance. H1299 cells, which express endogenously high SNTB2 levels and are radioresistant, were more sensitive to IR exposure when SNTB2 was down-regulated by siRNA. This suggests that overexpression of SNTB2 is linked to radioresistance in H1299 as well as H460R cells, implying that SNTB2 plays a critical role in the radioresistance of cancer cells. We are planning to explore the gain of function by SNTB2 using its ectopic overexpression in a further study and to clarify how SNTB2 plays a role in radioresistance.

In summary, we established H460R-radioresistant cells by fractionated low-dose IR and showed that these cells exhibit not only morphological changes but also a differential response to IR at the molecular level compared with parental cells. Among DEGs, SNTB2 played a role in radioresistance. Therefore, H460R cells will be helpful as an in vitro cellular model of radioresistance to evaluate its mechanism and to develop drugs to overcome radioresistance occurring during RT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (#2012029466) and by the National Nuclear R&D Program of the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (MEST) of the Republic of Korea. We appreciate Jung Hee Jung (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea) for analysis support of the microarray data.