Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts (RAGE), Its Ligands, and Soluble RAGE: Potential Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Therapeutic Targets for Human Renal Diseases

Article information

Abstract

Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is a multi-ligand receptor that is able to bind several different ligands, including advanced glycation endproducts, high-mobility group protein (B)1 (HMGB1), S-100 calcium-binding protein, amyloid-β-protein, Mac-1, and phosphatidylserine. Its interaction is engaged in critical cellular processes, such as inflammation, proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, and migration, and dysregulation of RAGE and its ligands leads to the development of numerous human diseases. In this review, we summarize the signaling pathways regulated by RAGE and its ligands identified up to date and demonstrate the effects of hyper-activation of RAGE signals on human diseases, focused mainly on renal disorders. Finally, we propose that RAGE and its ligands are the potential targets for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of numerous renal diseases.

Introduction

Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is a transmembrane protein that belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily [1]. As its name implicates, it can bind to advanced glycation endproducts, the resulting product of non-enzymatic glycosylation [2], and it also has the ability to interact with multiple ligands having common motifs as a so-called multi-ligand receptor. The ligands include high-mobility group protein (B)1 (HMGB1), S-100 calcium-binding protein, amyloid-β-protein, Mac-1, and phosphatidylserine [3]. Interaction between RAGE and its ligands activates various cellular processes, including inflammation, proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, and migration [4]. Expression of RAGE is different, depending on the organ, developmental stage, and cellular condition [5]. It is highly expressed during the embryonic stage, whereas it is mostly kept at low levels in adults [5, 6]. Mostly, it is stimulated by cellular stresses, such as inflammation, and is therefore easily found to be abnormally over-expressed in many human chronic diseases [7]. Accumulation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) is highly associated with the pathogenesis of diabetes, which causes serious consequences on metabolic systems [8]. In addition, expression of S100 proteins is reported to be involved in many cancers, including breast, lung, kidney, and thyroid cancers. Mostly, their up-regulation promotes tumorigenesis by stimulating metastasis through the activation of relevant transcription factors or by acting as chemoattractants [9, 10]. In addition to cancers, RAGE and its ligands are abnormally regulated in various types of chronic immune diseases, such as atherosclerosis, Alzheimer disease, and arthritis [7]. Increasing evidence demonstrates the critical role of RAGE signaling in many other human diseases and suggests its stimulating factors as potential biomarkers for diagnosis or therapy. In this review, we are going to summarize the RAGE signaling pathway and its contribution to the pathogenesis of human diseases, focused specifically on kidney diseases. Further, we propose the possibility of using RAGE and its ligands as therapeutic targets.

RAGE and Its Splice Variants

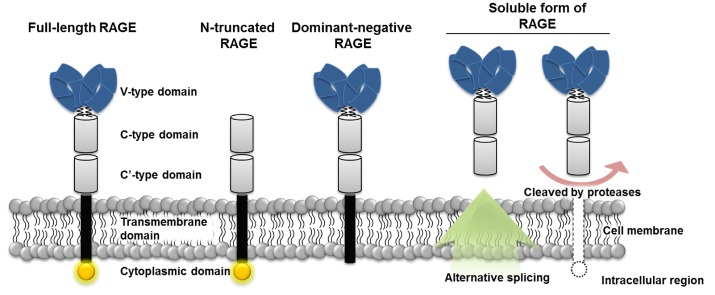

Human RAGE is encoded by a gene located on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class III region on chromosome 6 [11]. The mature RAGE has three main parts, consisting of extracellular, transmembrane, and cytosolic regions. The extracellular region is composed of one V-type and two C-type domains, and the V-type domain is responsible for interaction with multiple RAGE ligands. The transmembrane domain anchors RAGE to the cellular membrane, and signals transduce into the cell via the cytosolic domain [1, 12]. Besides, RAGE variants, represented by three forms, called N-truncated, dominant-negative, and soluble RAGE, can be generated either by natural alternative splicing or by the action of membrane-associated proteases (Fig. 1) [1]. The N-truncated form of RAGE lacks a V-domain so that it can not interact with ligands, whereas the cytosolic domain is missing in dominant-negative RAGE, which results in no signal transduction, though it can bind to ligands. Without the transmembrane domain, soluble RAGE is formed and is able to circulate out of the cell and act as decoys by preventing ligands from binding to RAGE [13]. Therefore, soluble RAGE can neutralize the effect of RAGE ligands, and many studies have suggested that this function might be applied to inhibition of RAGE signals in human diseases [14].

Structures of receptor for advanced glycation end products and its three main isoforms. Full-length receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) has three different extracellular domains (V, C, C') and one cytosolic domain. Multi-ligands bind to the V-type domain and transduce signals through the intracellular domain. The N-truncated isoform lacks the V-type domain, which fails to have receptor-ligand interactions. The dominant-negative form has no cytosolic domain and is not able to transduce signals into the cell. Soluble RAGE is formed either by alternative splicing or protease activity and is secreted and prevents ligands from binding to RAGE. V, variable domain; C, constant domain.

RAGE Signaling Pathways

RAGE and its ligands are highly expressed in developmental stages and enhance survival of neurons during development [15]. After embryonic development, these genes are down-regulated and kept a low expression levels during normal life, except for certain conditions, such as injury and aging [15]. Interestingly, unlike other receptors, expression of RAGE is positively regulated by its ligand stimulation, which means that increasing concentration of ligands leads to up-regulation of RAGE. So, RAGE signals are accelerated more and more by the accumulation of signal stimulants [16].

RAGE is found on the cell surface of various immune cells, and most of its ligands are mainly secreted by immune cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells; therefore one of the major roles of RAGE is involved in inflammation [7, 14]. Stimulation of RAGE by its ligands activates the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and it then translocates into the nucleus and activates its target genes, including several kinds of cytokines responsible for innate or adaptive immunity [17, 18]. Also, NF-κB can bind to glyoxalase (Glo1) and suppress its inhibitory activity on AGE production [19]. Target genes of NF-κB include anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl proteins; therefore, cell survival is also under the control of NF-κB [16]. In addition, the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway itself can be activated by RAGE stimulation. Specifically, activated RAGE is able to stimulate ERK, p38, and JNK, and it leads to induction of cell proliferation [20]. Another process involved in RAGE signaling is cell migration via transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signal cascades. TGF-β is activated by RAGE ligand stimulation and enhances its downstream signals. They include the Ras homolog family and Rho-associated kinase, and activation of these genes leads to stable actin filament formation and cell migration [21]. Due to RAGE signals being concerned with multiple cellular signaling pathways, in particular with immune responses and cell survival, the development of numerous human diseases is associated with it. They include diabetes, inflammatory diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases, and blockade of RAGE is increasingly proposed as a therapeutic target [4].

RAGE Ligands and Kidneys

Expression of RAGE and its ligands is kept at a low level in a wide range of cell types, including endothelium, smooth muscle cells, mononuclear phagocytes, neurons, and cardiac myocytes [22]. However, when RAGE ligands are accumulated by pathological development of relevant diseases, it alters the structure of tissues as well as compromise protein function in them [23, 24]. Also, increased circulating RAGE ligands induce the expression of their receptor, RAGE; therefore, RAGE ligand signals are stimulated as the ligands increase [16]. In kidneys, accumulation of RAGE ligands is well studied to contribute to both diabetic and non-diabetic nephropathy (DN). Firstly, AGEs have been found primarily to be up-regulated in renal basement membranes in diabetic nephropathies and in some other renal diseases, including glomerulosclerosis and arteriosclerosis, which are not related to diabetes [25]. In diabetes, AGEs are highly accumulated by increasing mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species, followed by high intracellular glucose levels [26]. Abnormally high concentrations of AGEs impair proximal tubular cells, which are responsible for regulation of AGE metabolism, resulting in damage to those cells and their function [27, 28]. Also, kidneys play key roles in the clearance of AGEs, such that the impaired structure of the kidneys by AGEs fails to degrade them [29]. In turn, more and more AGEs are accumulated as the kidney is damaged by the action of AGEs, and finally, it results in DN [27, 28, 30]. Recently, increasing evidence has shown that RAGE ligands other than AGEs, including HMGB1 and S-100 proteins, are also up-regulated in renal diseases. HMGB1 is a nuclear protein essential for regulating the physical interaction of DNA with certain transcription factors, such as p53 [29]; however, when it is released extracellularly, it is able to mediate inflammatory reactions and contribute to the pathogenesis of several diseases, including glomerulonephritis, lupus nephritis, and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [31, 32]. In addition, cell proliferation, migration, and invasion as well as inflammation are also activated in RCC via ERK1/2 activation [32].

Interaction between RAGE and its ligands changes renal cellular processes, including inflammation, proliferation, and migration, and they are highly significant processes to keep the normal function of kidneys; therefore, dysregulation of RAGE or its ligand concentrations might give fatal effects, leading to the development and pathogenesis of renal diseases.

RAGE and Renal Diseases

Diabetic nephropathy

DN is one of the diseases triggered by diabetes and finally leads to renal failure and elevation of arterial blood pressure [33]. Cellular mechanisms involved in the development and pathogenesis of DN include glomerular hypertrophy, production of oxidative stresses, fibrosis, and inflammation, followed by hyperglycemia. As mediators, renin, angiotensin, aldosterone, protein kinases, and NADPH are existing, and hyper-activation of them results in up-regulation of fibrotic and inflammatory factors, including TGF-β [33-36]. Also, hyperglycemia stimulates glycation and oxidation of macromolecules, which result in the formation of AGEs as endproducts [37]. Accumulated AGEs join in the up-regulation of inflammatory factors and oxidative stress and accelerate the pathogenesis of the disease [38].

Cardio-renal syndrome

Cardio-renal syndrome is a combined disorder having both heart and kidney dysfunction. The primary failed organ can be either the heart or kidney, and in both cases, the one that is diseased earlier impairs the other one, and finally, they negatively affect each other [37]. One of the suggested mechanisms making these two organs negatively interact with each other is mediated by AGEs [39]. Accumulation of AGEs is commonly observed in patients with both heart failure and renal disorders [40, 41]. With heart failure, increase of AGEs leads to inflammation, fibrosis, and delayed calcium uptake, which subsequently result in diastolic dysfunction. In addition, accumulation of AGEs in renal dysfunction is negatively affected by highly activated inflammation and fibrosis, and further damage of kidney structure impairs its own function of AGE clearance [39]. Symptoms of the disease might be enhanced by this vicious cycle, as well as with other multifactorial signaling pathways involved in the pathogenesis.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is one of the most highly prevalent inherited disorders and is characterized by the development of thousands of epithelial-lined, fluid-filled cysts in the kidney [42]. Cell proliferation, inflammation, and fibrosis are the major processes of the development and pathogenesis of the disease, and various factors, including chemokines and growth factors, are engaged in these signaling pathways [43-45]. Recently, several studies have reported that expression of HMGB1 and certain types of S-100 (S-100A8, 9) is increased around the cystic region and proposed them to be disease-stimulating agents [46-48]. So, inflammatory and growth factors secreted by cyst-lined epithelial cells and increased circulating AGEs finally result in compromised renal function at the end stage of the disease.

Renal cell carcinomas

RAGE and its ligands are reported to be abnormally expressed in various cancers, including breast, lung, kidney, thyroid, prostate, and oral cancers. S100 protein, one of the representative ligands of RAGE, which has at least over 20 subtypes, has been well reviewed to play major roles in tumor-related processes, including proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis, and invasion [10]. In renal cancer, S100A1 has been observed to be highly expressed in papillary RCC and oncocytoma, which are relatively common types of renal cancers, whereas it is absent in chromophobe RCC [49]. Likewise, a broad range of S100 proteins has been detected differently, depending on the subtype of renal carcinoma, which means that it should be a useful biomarker for discriminating the subtype of renal cancers if it is correctly examined [50]. In addition, HMGB1, another ligand of RAGE, has appeared to be up-regulated and interacts with its receptor for promoting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via the ERK pathway in RCC [32]. From this evidence, RAGE and its multiple ligands are increasingly suggested as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for different types of renal carcinomas.

Conclusions and Perspectives

In various types of renal diseases, including both diabetic- and non-diabetic disorders, RAGE and its ligands are commonly observed to be dysregulated. The major problem of these phenomena in renal diseases might be the vicious cycle that impairs kidney by increased AGEs or when other RAGE ligands fail to remove them, causing these ligands to accumulate and the relevant signals to accelerate. Therefore, numerous studies suggest RAGE and its ligands as new potential targets for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of renal diseases that have abnormal regulation of them. Firstly, ligands expression or secretion level can be used as a diagnostic or staging marker. S100B is already used in evaluations after treatment of melanoma in a clinical setting [51]. Secondly, more trials targeting RAGE ligands either with inhibitors of them or the soluble form of RAGE have been reported. Soluble RAGE treatment significantly alleviates the symptoms of nephritis in vivo [52], and in cancer studies, nude mice injected with soluble RAGE-over-expressing cells have shown remarkable inhibition of tumor formation [53]. With inhibitors of AGEs, several agents, including aminoguanidine and pyridoxamine, have been tried in humans; some of them have shown enhanced renal function in diabetic patients, but these trials were terminated early because of safety concerns [54, 55]. Finally, more recently, epigenetic regulation by microRNAs of molecules involved in RAGE signaling pathways is also being studied [56].