Introduction

Primary liver cancer is one of the most common cancers in the world, accounting for an estimated 600,000 deaths annually [1]. In Korea, liver cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths (10,946 death in 2010) [2]. In the United States, primary liver cancer has gained major interest, because the incidence of liver cancer has increased over the past 25 years, and the incidence and mortality rate of liver cancer are expected to double over the next 10 to 20 years [3-5]. Therefore, prevention and treatment of liver cancer are of great concern.

While primary liver cancer is one of the few cancers with well-defined major risk factors, such as hepatitis virus infection, alcohol consumption, and obesity, the molecular pathogenesis of liver cancer is not well understood [6-8]. Patients with liver cancer have a highly variable clinical course [7, 9], indicating that liver cancer comprises several biologically distinct subgroups. Therefore, it will be necessary to understand liver cancer at a genomic and molecular level for improved stratification of patients, identification of novel druggable targets, and development of personalized treatment, based on the biological characteristics of tumors in each patient.

Due to the complex nature of cancers that are initiated by activation of many different oncogenes or inactivation of different tumor suppressor genes and progress by additional genetic or epigenetic alterations, conventional gene-by-gene approaches are likely to deliver only a limited understanding of the biological and pathological characteristics of cancer cells. However, the recent development of technologies for gene expression profiling, genome-wide copy number analysis, and whole-genome sequencing has enabled the comprehensive characterization of entire cancer genomes. This information promises to improve our understanding of the genetic and epigenetic alterations driving the development of liver cancer, as well as ultimately provide guidance on personalized treatment of patients. Although these large-scale genomic data promise improvement in the treatment of liver cancer, challenges remain for the management and integration of these data for a better understanding of how these alterations give rise to the development of liver cancer and, most importantly, the translation of these findings into personalized patient treatment.

Approaches for Molecular Profiling of Liver Cancer

Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)

Since the discovery of frequent genetic rearrangements and copy number aberrations in the cancer genome [10], cytogenetic methods have been used widely to find the genetic changes in cancer genomes. The CGH method was the first tool to provide a genome-wide investigation of copy-number alterations in cancer [11]. Increased or decreased regions of copy number are believed to have either oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. Although the resolution of early CGH mapping technology is limited by 2 Mbp (high-copy-number amplifications) to 10 Mbp (low-copy-number amplification or deletion), this method has identified many loci for oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes in liver cancer. Multiple studies have reported amplification of the 8q24 loci, in which MYC is located [12-15]. Other studies also identified prevalent amplification of the 1q, 6p, and 17q regions and frequent deletion of the 8p, 16q, 4q, and 17p regions [12, 15].

Microarray-based technologies

Microarray technology has been used extensively to gather global-scale data from cell lines or tissues of interest. This technology was first used to make a quantitative assessment of mRNAs or non-coding RNAs. Gene expression profiling studies based on microarray technologies have identified conserved gene expression signatures that are significantly related with clinical outcomes or pathological phenotypes and have uncovered many subgroups of cancer that were not recognized with conventional approaches in a variety of cancers [16-18]. These approaches have been used successfully to identify therapeutic targets for various cancers and to predict overall survival or recurrence-free survival rates of cancer patients [19-21].

Use of microarray technology is not restricted to genome-wide gene expression profiling of cells or tissues but expands to uncovering single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with cancer risk, methylation status of gene promoters, DNA copy number alterations, protein expression profiling, and re-sequencing of cancer genomes. Because microarray-based CGH can provide copy-number analyses with much higher resolution than conventional CGH, it has quickly replaced conventional CGH [22, 23].

Microarray technologies were also adopted by the proteomics community. Protein microarray was quickly established by rapid improvements to miniaturizing western blotting and tissue lysate dotting technologies onto solid surfaces. There are two different experimental approaches for protein arrays: forward-phase protein array (FPPA) and reverse-phase protein array (RPPA). In FPPA, antibodies or polypeptides are printed on the slide surface, and each slide?is incubated with labeled tissue or cell lysate. This approach allows one to simultaneously measure multiple protein features, such as expression, interaction with peptide ligands, and protein phosphorylation, from the samples. In RPPA, an individual tissue lysate in printed on the slide surface, and each RPPA slide consists of hundreds or thousands of tissue samples. Each slide is then probed with one peptide ligand or antibody at a time, and a protein feature of interest is assessed and compared across many tissues or cell lines. Because RPPA needs only several thousands of cells to collect high-quality data, it is better suited for cancer research. In contrast, FPPA is not suitable for tissue-based studies, because it needs a large quantity of tissue or cell lysate for detection [24-27].

Next-generation sequencing

Due to the emergence of second-generation sequencing technologies that allow massive parallel collection of sequence information, the cost per base for sequencing the entire genome has reduced dramatically [28]. These new technologies provided unique opportunities to investigate all sequences of entire cancer genomes to uncover the genetic changes that arise during cancer development. Many different technologies have been developed by different companies: Roche Applied Science (454 Genome Sequencer FLX System; Indianapolis, IN, USA), Life Technologies (Sequencing by Oligonucleotide Ligation and Detection or SOLiD; Carlsbad, CA, USA), Illumina (Genome Analyzer II; San Diego, CA, USA), Helicos BioSciences (HeliScope Single Molecule Sequencer; Cambridge, MA, USA), and Ion Torrent Systems (now owned by Life Technologies, Ion Proton System).

These new technologies have been used to identify potential driver mutations in the development of liver cancer through whole-genome and -exome sequencing. The first sequencing of the primary liver cancer genome revealed a total of 11,731 somatic mutations [29]. Following studies showed that the CTNNB1, TP53, and EGFR genes were frequently mutated in liver cancer [30-33]. Additionally, the ARID family, including ARID1A, ARID1B, and ARID2, was mutated in about half of all tumors, suggesting a potential role of them in the development of liver cancer.

Gene Expression Profiling of Liver Cancer

In previous studies [18, 34-37], gene expression data from human liver cancer have identified several subgroups that are significantly associated with clinical outcomes, such as overall survival and recurrence-free survival. These findings strongly indicated that gene expression patterns faithfully reflect biological and pathological heterogeneity among patients with liver cancer and would be highly valuable in predicting the clinical outcome of patients. The current challenge for clinical use is to identify those who will not benefit from conventional treatments and to offer alternative therapies. If master drivers, such as genes or pathways determining the biological characteristics of the tumors, can be identified, we can explore their therapeutic potentials. However, gene expression profiling approaches are also limited, because they only provide information related to transcriptional regulation.

Integromics: Integration of multiple-omics data

Previous studies undoubtedly showed that gene expression patterns (or signatures) are useful markers that can stratify patients and offer useful prognostic information [18, 37-42]. The current research focus has moved to uncovering genetic/epigenetic factors that are key regulators of specific signaling pathways altered in malignant cancer cells, potentially guiding the discovery of new therapeutic (and druggable) targets [8, 43-45]. But, the selection of such candidates for future validations from long gene lists produced by genome-wide screening is a significant challenge because of potential confounding factors embedded in many genome-wide data from human cancers. Furthermore, because the gene expression data from tumor tissues only provide "snapshot" information of genetic/epigenetic alterations and lack in-depth information on interactive and time-dependent alterations during tumor progression, it is not easy to distinguish the driver genes from passenger genes whose alterations simply echo changes in cell proliferation or organ physiology.

As discussed earlier, CGH analyses have identified many recurrent candidate loci of DNA copy number changes in liver cancer. Some of these genomic regions have well-recognized tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes. However, because of the large number of candidate genes in the identified genomic loci, functional validation of all candidates would be impractical. Thus, there is an urgent demand for development of a new approach that would quickly prioritize candidates according to the likelihood of their direct involvement in tumor development.

In a previous study, systematic integration of gene copy number data and gene expression from the same patients has been proposed to identify potential driver genes [46]. This study demonstrated that DNA copy number alteration data provide additional prognostic significance. Integrative analysis of copy number alteration data and gene expression further identified 50 driver candidates whose activation was triggered by copy number amplifications of genes and also significantly associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes in liver cancer.

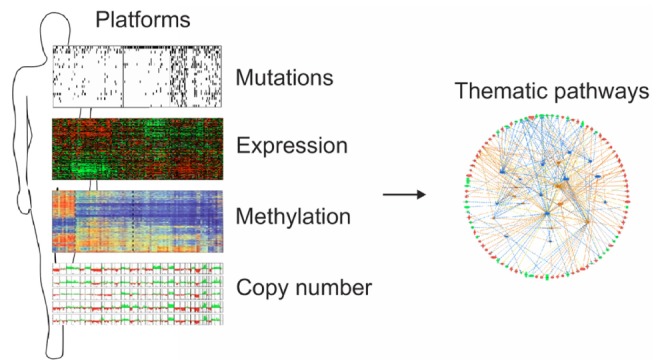

Alterations in DNA copy number and expression patterns of thousands of genes are important characteristics of many cancer cells. Because the use of high-throughput microarray-based technologies, mass spectrometry, and second-generation sequencers for the analysis of cancer genomes inevitably produces many false-positive results, it is not easy to select practical numbers of candidate genes for future evaluation of them as therapeutic targets and/or prognostic/predictive biomarkers. Therefore, it is important to combine two or more genomic scale datasets (e.g., array-based CGH data, promoter methylation, and expression of coding or non-coding genes), collected independently from the same tissues (Fig. 1).

RPPA is a newly established proteomic technology [24-27] that provides quantitative assessment of the expression and modification of many proteins. For example, the phosphorylation level of particular proteins can be estimated easily by using antibodies specific to certain phosphorylation sites of proteins. Use of the phosphorylation antibodies allows us to assess the signaling pathways by looking at many kinase substrates simultaneously through multiplexed phosphorylation-specific antibody analysis. However, assessment of signaling pathways by RPPA is restricted by the availability of antibodies with very high specificity. This limitation can be overcome by integration of multiple datasets for systematic analysis. Integration of proteomic data with genomic data would significantly help us have better insights into tumor development and progression. Furthermore, contributor genes (or drivers) will be quickly identified by integration of proteomic data with one or more genomic datasets.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Project: new opportunity for cancer genomics

TCGA is a landmark research program supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute and National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health in the United States that was started as a pilot project in 2006 and expanded later in 2009. The goal of TCGA is to collect comprehensive genomic and proteomic information on all major human cancers, including liver cancer. Initial efforts focused on glioblastoma, lung squamous cell cancer, and ovarian cancer as pilot projects [47-50]. By using various different platforms, TCGA currently gathers many different genome-wide data, including mRNA expression, microRNA expression, somatic mutations, copy number alterations, and promoter methylation. In addition, it also generates proteomic data by using RPPA technology. The project plans to collect genomic and proteomic data from more than 500 tissues per cancer type and release the data to the public without any restriction in use of the data (Table 1).

This ambitious project has identified novel driver genes and biomarkers on the basis of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic alterations. Some findings are clinically relevant and unexpected. For example, we have now learned that non-hypermutated adenocarcinomas of the colon and rectum are not distinguishable at the genomic level [51]. In lung squamous cell cancer, while KRAS and EGFR mutations, the most commonly activated oncogenes in lung adenocarcinoma, are extremely rare, alterations in the FGFR kinase family are common [49]. Thus, massive data from a large number of tissues have created an unprecedented opportunity for taking an integrated approach toward a systems-level understanding of disruptions in cellular and molecular pathways in cancer.

Conclusion

Genomics has become a dominant tool for understanding cancer biology, revealing unexpected surprises and providing cancer classification according to biological differences. The amount of liver cancer-related genomic data that have generated during the past few years is really incredible. Analysis approaches of these data have been advanced to efficiently process this information and allow us to perform integrated genome-wide analysis on a scale previously unthinkable. These approaches are also beginning to investigate the dense network of molecular pathways driving the development of liver cancer. The anticipated benefits of these data will be more a faithful assessment of prognosis than the current stage system, improved prediction of treatment response, and discovery of new therapeutic targets. Future challenges lie in translating this discovery into personalized treatment for the patient with liver cancer.