Interplay between Epigenetics and Genetics in Cancer

Article information

Abstract

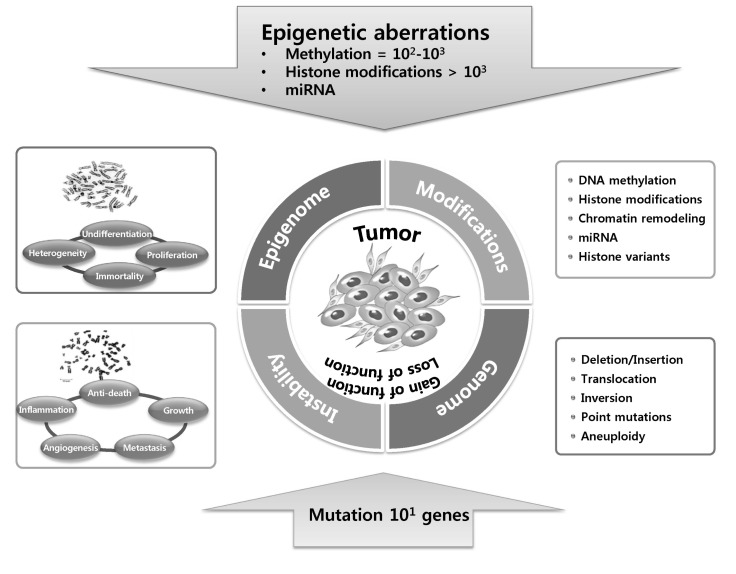

Genomic instability, which occurs through both genetic mechanisms (underlying inheritable phenotypic variations caused by DNA sequence-dependent alterations, such as mutation, deletion, insertion, inversion, translocation, and chromosomal aneuploidy) and epigenomic aberrations (underlying inheritable phenotypic variations caused by DNA sequence-independent alterations caused by a change of chromatin structure, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications), is known to promote tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Mechanisms involve both genomic instability and epigenomic aberrations that lose or gain the function of genes that impinge on tumor suppression/prevention or oncogenesis. Growing evidence points to an epigenome-wide disruption that involves large-scale DNA hypomethylation but specific hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes, large blocks of aberrant histone modifications, and abnormal miRNA expression profile. Emerging molecular details regarding the modulation of these epigenetic events in cancer are used to illustrate the alterations of epigenetic molecules, and their consequent malfunctions could contribute to cancer biology. More recently, intriguing evidence supporting that genetic and epigenetic mechanisms are not separate events in cancer has been emerging; they intertwine and take advantage of each other during tumorigenesis. In addition, we discuss the collusion between epigenetics and genetics mediated by heterochromatin protein 1, a major component of heterochromatin, in order to maintain genome integrity.

Genomic Instability in Cancer

Cancers have traditionally been accepted as diseases that are induced by the accumulation of a set of genetic mutations that have been considered the major causes of neoplasia [1]. But, is genomic instability a consequence of cancer progression or indeed a cause that drives cancer development? From about 1902 up until now, the involvement of genomic instability in tumorigenesis has long been the subjet of debate. In the beginning, Theodor Boveri's work with sea urchins showed that all chromosomes are required for normal development, known as the Boveri-Sutton chromosome theory. He had also suggested in 1902 that malignant tumors might be the result of a certain abnormal condition of the chromosomes, which may arise from multipolar mitosis. In the last century, remarkable findings and progresses in cancer research have added genomic instability to the hallmark list of cancer. Moreover, genomic instability generates the genetic and phenotypic heterogenicity and diversity that expedite tumorigenesis and the acquisition of cancer hallmarks.

Our genomes are constantly threatened by a number of challenges that are originating from extracellular and intracellular stimuli. Effective cellular responses to these enormous genotoxic stresses are acutely required to maintain genomic integrity. These stresses can induce a variety of problems in the DNA, such as double-strand breaks, single-strand breaks, oxidative lesions, and pyrimidine dimers. Eukaryotes have evolved elaborate DNA damage response (DDR) mechanisms to properly respond to the genotoxic stresses of these lesions. DNA damage induces several cellular responses, including checkpoint activation, DNA repair, and the triggering of apoptotic pathways for irreparable DNA damage (Fig. 1). Underlying these DDRs are functions of many tumor suppressors, which are frequently lost in cancers. To keep the genome intact, DNA replication must be carried out without error, and if there is a mistake, it should be repaired correctly. Also, to give time for cells to repair any defect, cells must have intact checkpoint responses. Replicated genomes must be passed to daughter cells without error; therefore, either miscopying or missegregation of chromosomes should be avoided. If these self-guarding machineries are not effective, cells that have problems should die. So, DNA replication, DNA repair, transcription, cell cycle machinery, chromosome segregation, and apoptosis are six domains to keep genomic integrity. Also, these DDRs are coordinately regulated and work together, via a series of signaling pathways that eventually activate surveillance and checkpoints for genomic integrity. In other words, cancer cells have problems in these machineries, leading to genomic instability.

On the road to cancer: genomic instability. Failure of DNA damage responses that conduct surveillance and checkpoints to guard genome causes genomic instability, the most common characteristic of human cancers. It has therefore been proposed that genomic instability contributes to and drives tumor initiation and development. Defects in the DNA damage responses generate genomic instability and facilitate tumorigenesis.

Epigenetics and Cancer

The word "epigenetics" was termed in the early 1940s to describe the events that could not be wholly explained by traditional genetics [2]. Conrad Waddington (1905-1975) defined epigenetics as "the branch of biology which studies the causal interactions between genes and their products which bring the phenotype into being" [3]. The epigenetic field now actively uncovers the molecular mechanisms underlying these phenomena, and epigenetics has been defined today as "the study of changes in gene function that are mitotically and/or meiotically heritable and that do not entail a change in DNA sequence" [4]. In other words, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression or phenotype, caused by mechanisms other than DNA sequences, and some of these epigenetic changes have even been shown to be heritable.

Our genetic information is stored in the form of DNA as genetic code, but it has to be copied into RNA as an intermediate messenger or non-coding functional component. This copying process, transcription, is regulated at several steps, including initiation, elongation, and termination, by a variety of mechanisms. Moreover, eukaryotic transcription has to deal with chromatin templates, such that histone modifications and chromatin remodeling vastly affect gene expression. Several types of cancers and genetic disorders are often associated with abnormal transcription, highlighting the importance of regulated transcription in the pathology and prevention of cancers.

Part of the genome has no transcribed information, which, however, has functional roles by various mechanisms. For example, cis elements (DNA sequences) can act as regulatory elements for transcription and replication. Also, centromeric DNA is required for mitotic and meiotic chromatin structure, and telomeric DNA plays a role in sheltering the ends of chromosomes and eventually guarding the genome. Indeed, centromeric and telomeric heterochromatin structures consist of specific repetitive sequences, which play a role in maintaining genomic integrity, such that heterochromatin structure is required for accurate chromosome segregation (centromere) and inhibiting DNA breakages and nonhomologous end-joining (telomere). Aneuploidy and chromosomal rearrangement, which are frequently observed in many cancers, are in part caused by aberrant chromatin structure.

Generally, genomic instability is often associated with cancer and can be indicative of a poor prognosis for some types of cancer. Lately, this concept has now been expanded to the field of epigenetics, and disorganization of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms is prevalent in cancer [5, 6]. Particular gene expression is determined not only by the genetic status of gene itself but also by epigenetic features, such as promoter regions, enhancers, and insulators, in chromatin and chromatin-modifying enzymes.

Mutations in tumor suppressors and/or oncogenes induce a loss or gain of function, respectively, and abnormal expression of these genes are likely to be linked to cancer initiation. Feinberg proposed a hypothesis that epigenetic alterations can induce genetic changes and contribute to tumor progression and also initiation [7]. Epigenetic changes occur without a change in the DNA sequence, and they can be induced by various factors, such as chromatin structure, including DNA methylation, histone variants, and modifications; nucleosome remodeling; and small non-coding regulatory RNAs (Fig. 2) [8]. In addition to histone proteins, DNA is associated with several nonhistone chromosomal proteins, including high-mobility group and heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), which can also play an important regulatory role in DNA-dependent processes, such as transcription, replication, recombination, and DNA repair, in a similar manner to histones.

Epigenetic mechanisms. Variations in chromatin structure but not DNA sequences modulate the use of the genome by 1) DNA methylation, 2) histone modifications (methylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation), 3) histone variant composition (dark), 4) chromatin remodeling (sparse or dense nucleosome occupancy), and noncoding RNAs.

Histone modifications and cancer

Nucleosomes are the basic units of chromatin that are composed of DNA wrapped around 8 histone core proteins [9]. One of best understood epigenetic mechanisms is histone modification. The histone N-terminal tails protrude from nucleosome cores and thus are subject to numerous modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, ADP-ribosylation, and citrullination, creating a massively complex bar code. It is thought that activating or repressive complexes are recruited to DNA and reshape chromatin into relaxed or a tightly packed structure, based on the histone code-instructions through a combination of histone modifications [10]. Like a writer, histone-modifying enzymes write the histone code via histone modifications and mark specific sites of the genome with histone modifications-for example, active promoter regions that are marked with augmented trimethylation in H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) inactive promoters that are marked with augmented trimethylated H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) or trimethylated H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me3), and enhancers that are marked with monomethylated H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me1) and/or acetylated H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27ac) [11-13]. These histone modification patterns are regulated by a variety of enzymes, including histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases, which introduce and remove acetyl groups, respectively. Similarly, histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and demethylases introduce and remove methyl groups. The combination of histone modifications largely affects gene expression by the recruitment of transcriptional regulatory proteins, which bind to specific modified histone markings. Thus, a combination of histone modifications acts as a histone code-high-level information residing above the genetic code, which is genetic information stored in the form of DNA.

Aberrant patterns of histone modification marks are often found in cancer. Advances in high-throughput sequencing have allowed for genome-wide mapping of chromatin changes that occur during tumor initiation and progression [8]. A recent report suggested that cancer cells often experience losses of histone acetylation and methylation, occurring predominantly at the acetylated Lys16 and trimethylated Lys20 residues in histone H4. These losses are also associated with the hypomethylation of repetitive DNA sequences, which is a well-known characteristic of cancer cells [14].

DNA methylation and cancer

One of the best studied epigenetic signals is DNA methylation. In contrast to a dazzling variety of histone modifications, DNA methylation is a simple covalent chemical modification, resulting in the attachment of a methyl (CH3) group at the 5' carbon position of the cytosine ring. When methyl groups are attached to the DNA in genes, transcription of these genes is usually turned off, and then these genes are silenced. When a cell divides, its DNA is copied via replication and divided equally into two daughter cells during mitosis. During this process, the pattern of DNA methylation can also be copied onto the new daughter DNA, allowing the information that determines whether a gene is "on" or "off" to be inherited to the two daughter cells [15].

DNA methylation in mammals occurs mostly at CpG dinucleotides, and methylation of CpG islands explains a stable gene silencing mechanism [15]. In normal somatic cells, most (over 50%) CpG islands are unmethylated. DNA methylation is important for the regulation of non-CpG islands, CpG island promoters, and repetitive sequences to maintain genome stability [15, 16]. Furthermore, DNA methylation plays important roles in X chromosome inactivation, imprinting, embryonic development, silencing of repetitive elements and germ cell-specific genes, differentiation, and maintenance of pluripotency [16-18]. DNA methylation is controlled by a family of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) that catalyze the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl-L-methionine to the 5' position of cytosine bases in the CpG dinucleotide. Methyl-binding domain (MBD) proteins, such as MeCP2, MBD1, MBD2, and MBD4, bind to methylated CpG sites and are involved in transcriptional repression [19].

In cancer, hypomethylation usually occurs at repeated DNA sequences, such as long interspersed nuclear elements, whereas hypermethylation predominantly involves CpG islands [20]. DNA hypermethylation has been shown to result in abnormal silencing of several tumor suppressor genes in most types of cancer [21]. Thus, DNA methylation is grossly reduced, but DNA hypermethylation is specifically and locally augmented at CpG islands at tumor suppressor genes (Table 1); yet, its involvement and role in tumorigenesis remain controversial. Yet, experimental progress has added an emerging epigenetic aberration, "aberrant DNA methylation," to an established cancer hallmark, "genomic instability." DNA hypermethylation at tumor suppressors or genes having tumor suppressive functions is more frequent than their mutations in cancer cells. Hundreds to thousands of genes are hypermethylated in cancer cells, while only tens of genes are mutated. Epigenetic silencing via DNA methylation results in gene inactivation and promotes carcinogenesis, indicating that DNA methylation impinges on carcinogenesis.

MicroRNA and cancer

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) constitute a class of small noncoding RNAs that have epigenetic functions in posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression via mRNA degradation or sequestering and translational repression and have physiologically essential roles in most cellular processes. Therefore, their dysfunction is implicated in human diseases, including cancer, as well as inherited diseases and developmental defects. The human genome may encode over 1,400 miRNAs, which frequently target many genes related to cancer development or prevention [22]. In light of the linkage between miRNA and cancer, they have been categorized into three groups: oncogenic, tumor-suppressive, or context-dependent miRNAs [23]. In tumorigenesis, the loss of tumor-suppressive miRNAs promotes the expression of target oncogenes, while increased expression of oncogenic miRNAs can repress target tumor suppressor genes [23]. Mutations in a miRNA can disrupt its recognition of binding targets and further result in oncogene activation and/or tumor suppressor repression. Indeed, oncogenic miRNAs, such as miR-155, miR-21, and miR-17 to -92, whose expression triggers cancer development, appear to be amplified, and tumor suppressive miRNAs, such as miR-146 and miR-15 to -16, whose loss triggers cancer development, appear to be downregulated in cancers [23]. Moreover, mutations of miRNAs, including miR-101 and miR-29, targeting epigenetically modifying enzymes, such as EZH2 [24, 25] and DNMT3 [26], respectively, are often found in human cancers. Aberrant expression or mutation of such miRNAs is likely to further reinforce extensive and heavy epigenetic alterations [23, 27] and might have effects on histone or DNA methylation at promoters of other miRNAs that target oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Underexpression of miR-127, which targets BCL6, is correlated with abnormal methylation at its promoter in cancer [28]. In the course of remarkable progress in the study of cancer epigenetics, new observations linking aberrant miRNA expression and tumorigenesis imply that miR-mimic molecules might serve as effective therapeutics by replacing tumor suppressor miRs or targeting oncogenic miRs.

Epigenetics and Genetics Cooperates in Cancer Development

Many types of human cancers and disorders/diseases are often induced by misregulation of gene expression. Mechasnims for this misregulation involve both genetic mutations (genetic instability) and epigenetic modifications that disrupt the function of genes, including tumor suppressor and oncogenes, as well as other genes related to cancer, via altered activity or expression of the products of the genes. Given the importance of epigenetic dysregulation in tumor initiation and development, differentiating causative "drivers" (causes) and resulting "passengers" (outcomes) is becoming an important priority for cancer biology as well as epigenetics. Driver genes have to be essential for cancer causation, whereas passenger genes are not necessary [29]. By the development and improvement of technology, it may eventually be possible to accurately and minutely distinguish epigenetic aberrations of driver genes [30, 31]. Many current clinical investigations and trials of epigenetics-based cancer therapy, highlighting the reciprocal regulation of epigenetically modifying enzymes, miRNAs, and genetic defects in cancer, have come from scientific discoveries of how epigenetic aberrations in cancer manage to play a key role at every stage of tumorigenesis and have such a profound impact on the underlying mechanisms of tumorigenesis. Nevertheless, cooperation between epigenetics and genetics in tumorigenesis (Fig. 3) is the subject of debate. The interconnection between these two processes becomes increasingly apparent, in large part because it is realized that mutations of various epigenetic modifier genes are associated with human cancers [32]. The mutation of epigenetic modifiers presumably fosters profound epigenetic anomalies in terms of DNA methylation, histone modifications, miRNA, and nucleosome positioning and occupancy, which expedites global dysregulation of gene expression. Underlying this dysregulated epigenome is genomic instability, which generates mutations in epigenetic modifiers that induce abnormal gene expression, which may predispose one to cancer [32], although this remains to be demonstrated. Insight into its underlying mechanisms helps establish the epigenetic involvement in tumorigenesis. Because epigenetic processes involve a number of overlapping and interconnected mechanisms and pathways, it is difficult to definitely identify the cellular and molecular identities and the mechanism(s) underlying the epigenetic outcomes and phenotype. Based on studies of cell lines that have originated from tumor tissues and tissue samples collected from cancer patients, aberrant epigenetic marks can result in inappropriate expression of genes that are associated with cancer (tumor suppressors and/or oncogenes). It is now generally accepted that human cancer cells harbor global epigenetic abnormalities and that epigenetic alterations may be the key to tumor initiation and development [5, 6, 8]. The cancer epigenome is characterized by substantial changes in various epigenetic regulatory layers; herein, we introduce some important examples of epigenetic disruptions that cause mutations of key genes and/or alterations of signaling pathways in cancer development.

Epigenetic silencing is more frequent that mutations in cancer cells. In cancer cells, hundreds to thousands of genes are hypermethylated (DNA methylation), histone codes at more than thousands of genes are aberrantly modified via histone modifications or histone variant compositions, and miRNA expression is dysregulated, while tens of genes are affected by mutations. Both epigenetic silencing and inactivating mutations or deletions result in gene inactivation.

However, this idea has now been expanded to be a scientific norm by consolidating and incorporating the altered epigenetic regulatory mechanisms that are common and prevalent in cancer [5, 6]. Both genetics and epigenetics ultimately involve abnormal gene expression-i.e., phenotype. The expression level of a particular gene is determined by its context at the genetic level, which consists of several cis elements, including promoters, regulatory regions, enhancers, and insulators, each of which recruits specific transcriptional proteins for activation, repression, and constitutive or facultative transcription by various mechanisms. In other words, cis elements can act as a primary platform for recruiting epigenome-modifying enzymes and/or chromatin remodeling factors. The modified epigenome follows immediately and acts as a secondary platform for transcriptional effector machinery. Finally, transcription is turned on or off, and its level is determined by the overall epigenomic context.

The genetic road to cancer is relatively straightforward: mutation of tumor suppressors and/or oncogenes causes either a loss or gain of function and abnormal expression-namely the very relationship between altered genotypealtered phenotype. On the contrary, there are no genetic changes but a sick phenotype in the epigenetic road to cancer. The epigenetic pathway to cancer is much more complicated and roundabout and is determined by integrating numerous epigenetic variations, including DNA methylation, histone variants and modifications, and nucleosome remodeling, as well as small non-coding regulatory RNAs (Fig. 2) [8]. During tumor initiation and progression, the epigenome undergoes multiple alterations, including a genome-wide loss of DNA methylation (hypomethylation), frequent increases in promoter methylation of CpG islands, and aberrant changes in nucleosome occupancy and histone modification profile, and these epigenetic aberrations drive tumor cell heterogeneity, as well as tumorigenesis.

Epigenetic aberration is a major feature of cancer, but its etiological role in tumor development remains controversial. This contrasts with genomic instability, which is known to produce cancer-causing mutations. Recent evidence demonstrates that a dysregulated epigenome can promote tumorigenesis via altered gene expression; however, the question of whether a dysregulated epigenome can predispose one to DNA damage and generate genomic instability remains clearly unaddressed. Only few possible mechanisms have been proposed; one possible mechanism by which chromosome segregation errors promote tumorigenesis is by inhibiting chromosome condensation for mitotic entry or destabilizing heterochromatin at centromeres, which facilitates chromosomal misalignment and accelerates the formation of unattached chromosomes or malfunctioning spindles. A second mechanism is chromosomal breakage and non-homologous end-joining, which result in chromosomal rearrangement and extensive structural alterations in chromosomes. Third, a dysregulated epigenome at telomeres promotes its elongation or chromosomal rearrangement. Intriguingly, histone deacetylase inhibitors or knockdown/knockout of epigenome modifiers can induce DNA damage, but whether this DNA damage can indeed predispose one to cancer remains unestablished.

Epigenetic Control by HP1 Ensures Genome Integrity

Heterochromatin protein 1

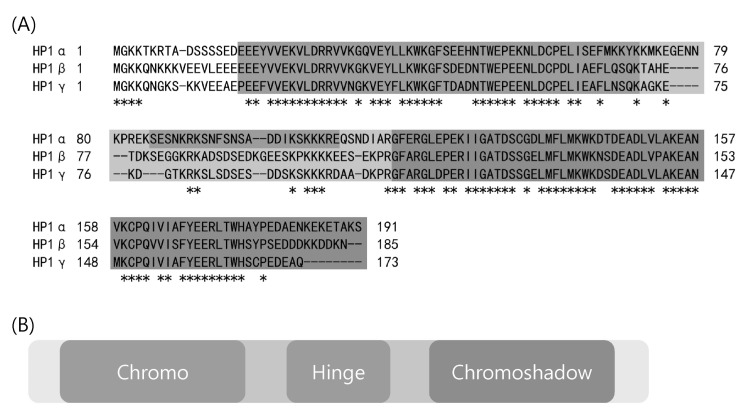

HP1 was originally identified in Drosophila, functioning in heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing. Three different paralogs of HP1 are found in Drosophila melanogaster: HP1a, HP1b, and HP1c. Subsequently, orthologs of HP1 were also discovered in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Swi6), xenopus (Xhp1α and Xhp1γ), chicken (CHCB1, CHCB2, and CHCB3), and mammals (HP1α, HP1β, and HP1γ) (Fig. 4) [33, 34]. HP1 binds directly to the methylated K9 residue of histone H3 (H3K9me), a surrogate marker for transcriptionally repressive heterochromatin, and is critical for its maintenance [35-37]. Therefore, its canonical functions include maintaining heterochromatin integrity as a fundamental unit of heterochromatin, silencing by heterochromatin formation, and gene repression by heterochromatization of euchromatin. HP1 proteins are characterized by two conserved domains: the chromodomain (CD) in its N-terminus and the chromo shadow domain (CSD) in the C-terminus (Fig. 4). The CD has been shown to directly bind H3K9me, while the CSD is implicated in interacting with a partner protein and its homo- and hetero-dimerization. Two CD and CSD domains are separated by a hinge domain that is involved in DNA and RNA binding (Figs. 4 and 5) [38, 39]. HP1 interacts with numerous epigenomic modifiers with different cellular functions in different organisms (Fig. 5). Some of these HP1-interacting partners are histone methyltransferse, DNMT, and methyl CpG-binding protein MeCP2 (Fig. 5), supporting its role in epigenomic modification.

(A) Heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) paralogs in human. Amino acid sequence alignment of HP1α, β, and γ. (B) A schematic diagram of the HP1γ polypeptide. The HP1γ polypeptide has an N-terminal chromodomain, a hinge domain, and C-terminal chromoshadow domain.

Interactions of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) with a diversity of proteins and its possible roles (references in parentheses). The putative cellular functions of protein-protein interactions of HP1 are shown in circles. Some of their biological significance is not yet clarified. Only the proteins that have been shown to interact with HP1 in vivo are listed here.

HP1 and chromatin structure

HP1 proteins are mostly enriched at heterochromatin centromeres and pericentromeric regions, telomeres and subtelomeric regions, and transcriptionally repressive genes. However, HP1 is also found at euchromatic sites [40, 41], though whether euchromatic HP1 has a disparate function and which HP1 paralog is located at euchromatin remain unclarified. A structure-based study revealed that a hydrophobic pocket of the HP1 CD interacts with histone H3K9me [42]. This epigenetic mark is generated by a conserved family of HMTs, named after the Drosophila member SU (VAR)3-9, discovered as a suppressor factor involved in position-effect variegation [43, 44]. Both HP1 and SU (VAR)3-9 function in heterochromatin structure formation. Loss of SU(VAR)3-9 results in displacement of HP1 from heterochromatic regions and alteration in gene repression [45]. Mechanisms by which HP1 localizes to euchromatin sites appear to involve more than the recognition of H3K9me, which is poorly understood. An alternative mechanism of localization might be mediated via interactions between its CSD and other factors. HP1 CSD homodimerizes through an alpha-helical region and generates a platform that can interact with the PxVxL motif in its interacting partner proteins, such as DNMT1/3, SU(VAR) 3-9, and the p150 subunit of CAF-1 (Fig. 5) [46]. A second alternative mechanism of localization on chromatin involves interactions with RNA through a hinge domain, such that association of HP1 with specific loci in Drosophila and centric regions in mouse makes them susceptible to RNase treatment [39, 47]. For example, it has been demonstrated that an HP1 subcode with sumoylation plays a role in heterochromatin architecture, via its association with microsatellite RNAs [48]. A third mechanism for chromatin localization is found at the distal ends of Drosophila telomeres, where HP1 is thought to bind DNA directly [49]. However, in mammals, localization of HP1 proteins to telomeric regions occurs via H3K9 association [50-53]. Together, HP1 localizes to chromatin using both genetic (DNA or RNA sequence) and epigenetic (histone modification) information.

HP1 subcode: above the histone code

Recently, the "HP1 subcode" hypothesis is emerging in addition to the genetic code and histone code: a hypothesis that the transcription of genetic information encoded in DNA-i.e., genetic code-is regulated in part by histone variants, modifications, and nucleosome occupancy. The histone code hypothesis states that the type and combination of histone modifications are interpreted by the cell as instructions for organizing gene expression and constitutes the most advanced conceptual framework for deciphering the genetic information cascades that regulate gene expression. Further, a combination of HP1 paralogs and modifications may be defined as a second regulatory layer of the code-that is, a subcode-involved in transcription, especially gene silencing, within the general context of the histone code. The HP1 subcode can be secondary-level information residing above the genetic and histone codes and regulate HP1 interactions with other key proteins, further modulating gene silencing and possibly replication, recombination, and DNA repair. In this review, we will discuss the interplay between genetics and epigenetics in cancer through HP1.

Pleiotropic functions of HP1

Besides heterochromatin formation and the maintenance functions of HP1, this protein also recruits the cohesin complex to pericentromeric heterochromatin for centromeric sister chromatid cohesion. Recent studies have shown that HP1 does not always act in the context of heterochromatin and functions in gene activation and telomere maintenance [38]. Furthermore, HP1 interacts with many different proteins, including transcription factors, chromatin regulators, and DNA replication and repair factors, as well as components of the nuclear envelope [54], and functions via collaboration with its interacting proteins in diverse cellular processes, including mitosis progression [55, 56], DNA damage repair [57-59], transcription [60-62], and chromatin remodeling (Figs. 4 and 5) [63, 64].

Whether and How HP1 Is Associated with Cancer

HP1-mediated transcriptional regulation in response to DDR

Recently, we proposed a mechanism in which HP1 could recover transcription in response to DNA damage signals [60]. HP1 accumulates at the promoter before DNA damage, but BRCA1 is recruited to the promoter after the damage while promoter-resident HP1 is disassembled. Importantly, HP1 assembly is recovered post release from the damage in a BRCA1-HP1 interaction-dependent manner and simultaneously targets SUV39H1 to chromatin. HP1/SUV39H1 restoration at the promoter results in BRCA1 disassembly and histone methylation. In the aftermath, transcriptional repression resumes. This report provides a partial explanation for the targeting of HP1 to a variety of chromatin structures and its functions in constructing de novo heterochromatin from euchromatin or facultative heterochromatin, in addition to maintaining previously existing heterochromatin. In addition, a role in the DDR for HP1, previously implicated in heterochromatin and silencing, reveals new connections between tumor-suppressive processes that maintain genome integrity.

HP1 depletion activates DDRs

Recent studies have revealed the possible link of HP1 proteins to the DDR [59, 65, 66]. However, the spatial and temporal regulation of the association and dissociation of HP1 with chromatin in response to DNA damage remains unclear and controversial. A couple of studies have reported that DNA damage induces the transient dissociation of inhibitory HP1 proteins from DNA damage sites in order to help DNA repair proteins/complexes gain access to chromatin [65, 66]. In contrast, another study has indicated that HP1 is recruited and associates at DNA damage sites, such as UV-induced DNA lesions and chromosomal breaks upon DNA damage, which helps the DDR via its dynamic dissociation and association with DNA damage sites [59]. Recently, Lee and colleagues [67] have shown that HP1 promotes homologous recombination repair via recruitment of BRCA1 to damaged chromatin. Together, chromatin protein HP1 plays some unelucidated roles in keeping genomic as well as epigenomic integrity.

Whether and how HP1 is related to cancer

An aberrant epigenome in cancer cells results from an altered chromatin structure resulting from alterations in chromatin-modifying enzymes and/or chromatin proteins. Examples of HP1γ-interacting proteins are the histone proteins, epigenetic modifiers, transcription factor family, DNA repair factors, and replication proteins (Fig. 5) [48, 54-57, 60, 62, 63, 67-80]. The diversity of HP1γ-associated proteins has increased with the recent discovery that HP1γ interacts with BRCA1, a tumor suppressor that guards the genome. In addition, HP1γ is involved in the recovery of BRCA1-mediated transcription post-DDR. There is no direct evidence that HP1γ is a component of BRCA1-mediated tumor suppression. However, a couple of tantalizing observations support this possibility: HP1γ expression is elevated in prostate cancer [81], and in addition, depletion of HP1 paralogs activates the formation of DNA damage repair foci. HP1 paralogsare recruited to repair foci and promote DNA repair, following DNA damage. This raises the question of whether increased or decreased HP1γ can foster or suppress tumor initiation and development. In light of the HP1γ-BRCA1 association, it would be intriguing to test whether the genes encoding the HP1 family are also overexpressed in breast cancers. It would also be interesting to test whether the HP1 family impinges on genomic stability.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Lee lab for helpful advice. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (2012M3A9B2052871, 2010-0018546, 2011-0030043).