|

|

- Search

| Genomics Inform > Volume 16(4); 2018 > Article |

|

Abstract

Cirsium japonicum belongs to the Asteraceae or Compositae family and is a medicinal plant in Asia that has a variety of effects, including tumour inhibition, improved immunity with flavones, and antidiabetic and hepatoprotective effects. Silymarin is synthesized by 4-coumaroyl-CoA via both the flavonoid and phenylpropanoid pathways to produce the immediate precursors taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol. Then, the oxidative radicalization of taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol produces silymarin. We identified the expression of genes related to the synthesis of silymarin in C. japonicum in three different tissues, namely, flowers, leaves, and roots, through RNA sequencing. We obtained 51,133 unigenes from transcriptome sequencing by de novo assembly using Trinity v2.1.1, TransDecoder v2.0.1, and CD-HIT v4.6 software. The differentially expressed gene analysis revealed that the expression of genes related to the flavonoid pathway was higher in the flowers, whereas the phenylpropanoid pathway was more highly expressed in the roots. In this study, we established a global transcriptome dataset for C. japonicum. The data shall not only be useful to focus more deeply on the genes related to product medicinal metabolite including flavolignan but also to study the functional genomics for genetic engineering of C. japonicum.

Cirsium japonicum is a wild perennial herb found in many areas of Korea, Japan, and China. C. japonicum is used as an anti-haemorrhagic, anti-hypertensive and uretic agent in traditional Chinese medicine [1]. In traditional medicine, C. japonicum is sometimes used for the management of different types of cancer, including liver and uterine cancer and leukaemia [2]. To date, many studies have explored the effects of C. japonicum on various diseases. However, no reports have performed molecular biology studies or investigated comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic data in C. japonicum.

In Europe, silymarin, which is synthesized in Silybum marianum, belongs to the same family as C. japonicum and is prescribed for the treatment of chronic liver disease and the prevention of recurrent hepatitis C in liver transplant recipients [3, 4]. Silymarin is the key component of S. marianum and includes flavonolignans (silibinin, isosilibinin, silychristin, isosilychristin, and silydianin) and a flavonoid (taxifolin). Studies suggest that silymarin exerts a protective effect on the liver in alcoholic-induced liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative liver [1, 5]. This major bioactivity has also been reported in C. japonicum DC, which has properties similar to those of S. marianum [6]. C. japonicum var. spinossimum is often compared to the basic species thistle (C. japonicum Fisch ex DC) [7]. Silymarin is synthesized through the phenylpropanoid pathway and transforms phenylalanine into 4-coumaroyl-CoA, which acts via both the flavonoid and monolignol pathways [8–10].

Significant progress has been achieved in the field of next generation sequencing, which is driven by genomic/transcriptomic-based inquiries in biology. High-quality sequences are generated in a high-throughput manner at a low cost and with little labour. The Illumina platform is a highly utilized platform employed for transcriptome analyses of various model and non-model organisms and medicinal plants due to its potential for a high sequence yield [11–13]. The RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) method is superior to whole genome sequencing because RNA-Seq only studies the transcribed regions and provides a comprehensive and integrated view of the transcriptome with the precise locations of the transcriptome boundaries [14]. RNA-Seq is currently a very popular method used to examine both coding and non-coding gene annotations. Remarkable progress has been achieved in the exploration of medicinal plants at the genomic and transcriptomic levels, and the ultimate goal is to identify genes that are involved in biologically active phytocompounds and related pathways [15–18].

In this study, we established transcript databases for C. japonicum var. spinossimum and provided additional genetic information for further genome-wide research and analyses. We also aimed to investigate the transcripts that contribute to the production of silymarin in this herb.

C. japonicum was obtained from the National Institute of Biological Resources, Korea. The flower, leaf, and root tissues were immediately dissected and grinded in liquid nitrogen for the RNA extraction. The total RNA was extracted using Hybrid-R (Geneall, PN: 3033522) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The total RNA was further treated with RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) and purified on an RNA-purification column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) to eliminate possible gnomic contamination. The RNA quality was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and RNA samples with RNA integrity number values above eight were used for the subsequent cDNA synthesis. The DNA was sheared with an average of 500 bp fragment sizes. The TruSeq Library Preparation Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used to construct the DNA library according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA libraries were sequenced with 150-bp paired-end sequencing using an Illumina Hiseq2500. The quality of the constructed libraries was confirmed by a LabChip GX system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

The raw data were quality-filtered using trimmomatic with the following options: minimum quality of base (3); sliding window (4); average quality phred score (20); and minimum read size (50 bp). The primer and adapter sequences incorporated during cDNA synthesis were removed. The de novo assembly of the reads was performed using Trinity assembler with the default options to form the contigs. Based on the final transcriptome isoform sequences, the candidate-coding regions were identified using TransDecoder software (The Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). A BLAST analysis was carried out using these candidate-coding regions against the UniProt and NCBI non-redundant (nr) protein databases to determine the sequence similarity with genes from other species at an E-value cut-off of 1 × 10−6. The functional categories of these sequences were matched to the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) algorithms using blast. The GO analysis, including the biological function, cell component and molecular function categories, and the KEGG pathway analysis were performed using the GOstats program (Roswell Park Center Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA) as implemented in the sequence annotation tool Blast2GO (BioBam Bioinformatics SL, Valencia, Spain). The gene annotation and GO analysis were performed at NICEM, Seoul National University (Seoul, Korea). The assembled data were arranged according to the read length, GenBank number, E-value and species, and the specific composition of the GO terms was calculated and presented in a bar chart according to the percentage.

The filtered raw reads were mapped to the C. japonicum contigs that were determined by the de novo assembly and annotation using HISAT2. The expression values in RNA-Seq were calculated based on the read count, and the expression levels were analysed using the counts (number of fragments) and FPKM (Fragments per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped reads). The differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis among the leaf, flower and root tissues was carried out using the edgeR package [18]. The significantly DEGs were screened at a threshold false discovery rate < 0.05 and an absolute log2-fold change value > 1. Subsequently, GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses of the DEGs were performed.

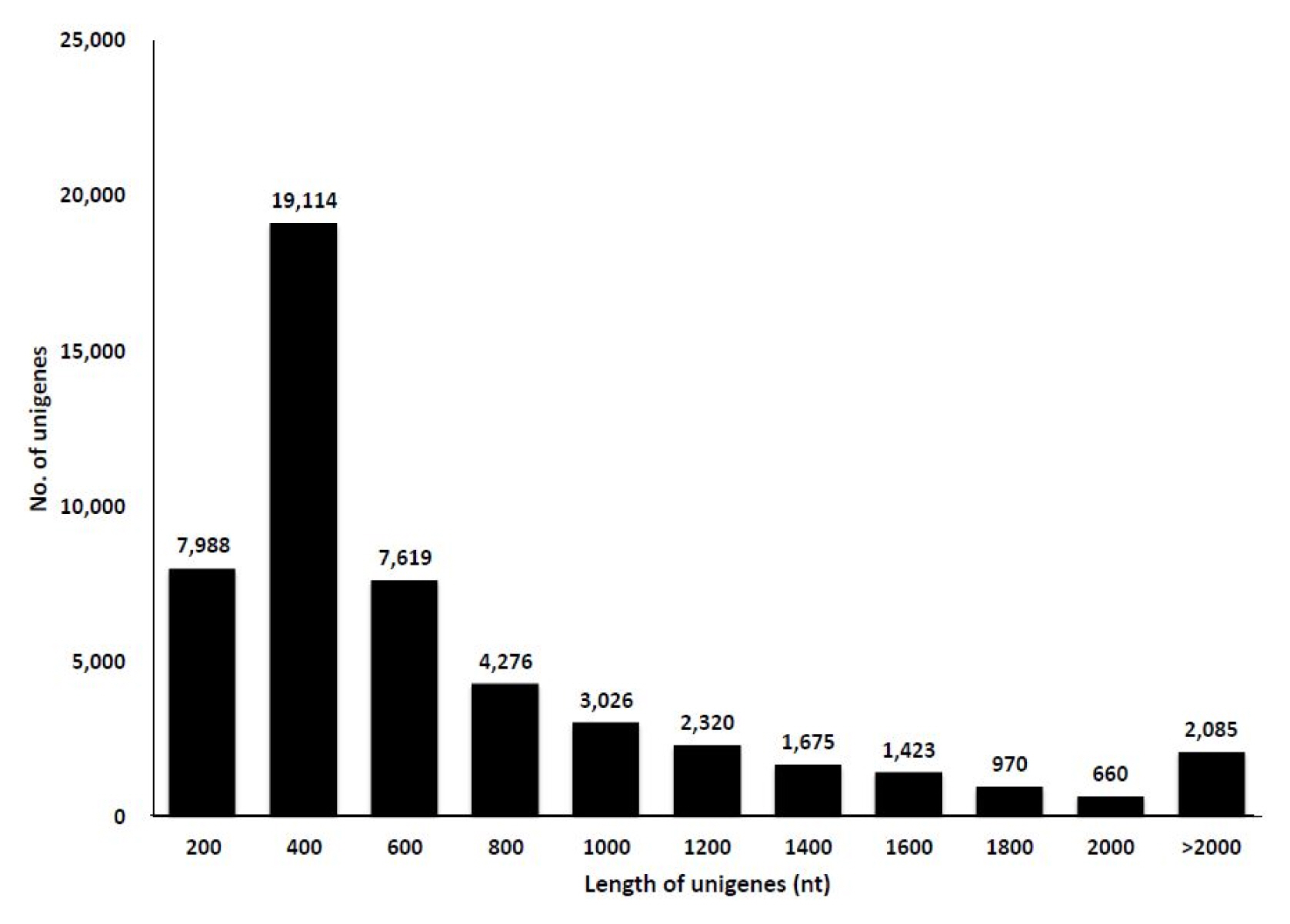

To study the transcriptome of C. japonicum, three tissues, viz., flowers, leaves, and roots, were extracted, and the RNA was isolated. The total RNA from each sample was used for the mRNA preparation, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis and library preparation. De novo assembly was selected since a reference genome for C. japonicum is lacking. Each library was sequenced using the Illumina Hiseq2500 platform. The platform generated 74,566,546 raw reads for C. japonicum for the whole transcriptome, which accounted for 18Gbases of sequence data (Supplementary Table 1). These data were further subjected to a quality check and adaptor trimming (using the trimmomatic 0.30 tool), generating 67,153,874 high-quality paired end reads (Tables 1 and 2). Then, an error correction of the data was performed, and 66,078,302 reads were obtained. The paired end sequencing yielded on average a 64× sequencing depth. The mean Phred value was above 20, and the short reads (>50) were removed. The whole transcriptome was assembled using the Trinity program, resulting in 51,133 unigenes, accounting for 37 Mbases, with a mean size of 648.36 bp. The length distribution of all unigenes is shown in Fig. 1. The GC content was distributed within 42%–45%. The minimum size of the transcripts was 147 bp, whereas the maximum size was 15,402 bp (Table 1).

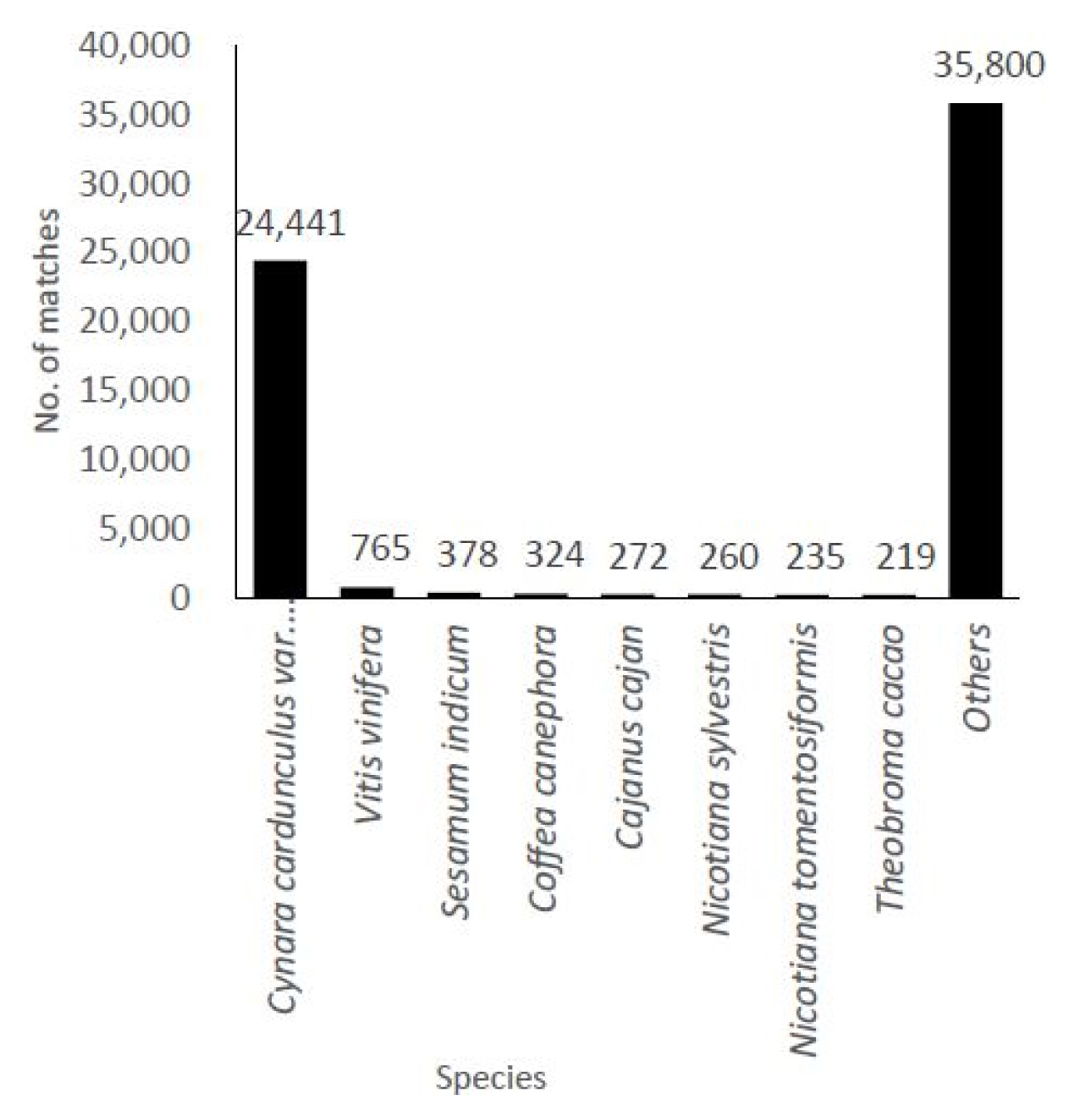

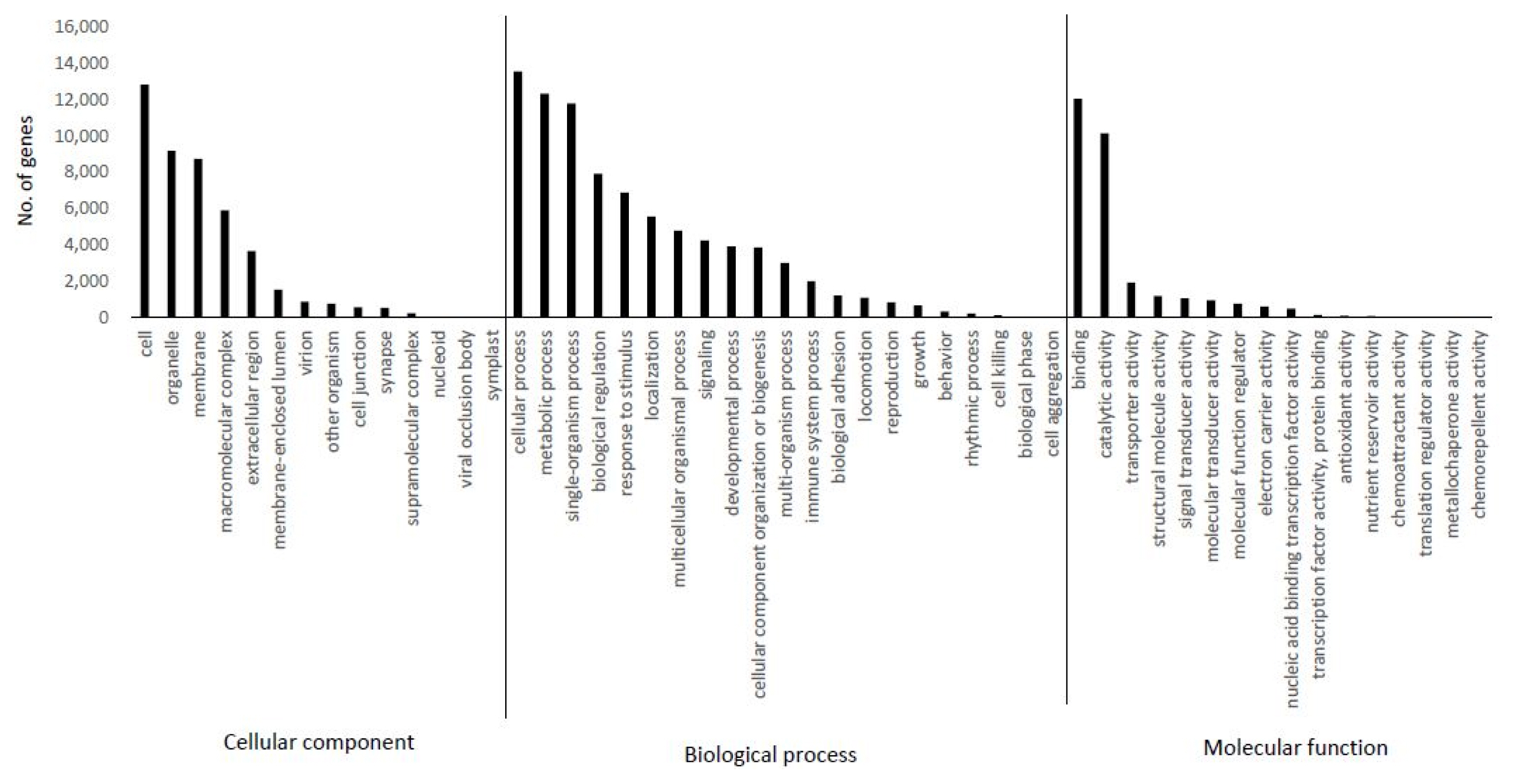

The transcripts derived from C. japonicum were subjected to annotation using the BLASTX program based on a homology search against the NCBI non-redundant (nr) protein database. The highest homologous subject in each contig was selected for gene annotation. The identified contigs were contigs that hit to variable species with a high similarity homologous BLAST search. In total, 33,525 (65%) unigenes were annotated using the BLASTX program. The similarity distribution demonstrated that C. japonicum was highly similar to Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus (72%) (Fig. 2). GO broadly categorizes genes into one of three classes (biological process, cellular component, and molecular function) to describe their involvement in plant biological phenomena. The transcript functions were predicted with the help of the GO terms using Blast2GO based on their similarities to transcripts available in the nr database. All assembled transcripts were surveyed at an E-value of 1 × 10−6. The numbers of genes assigned to the biological process, molecular function, and cellular component categories were 9,336, 2,371, and 1,163, respectively (Fig. 3). Among the biological processes transcripts, the highest number of transcripts was assigned to cellular processes (13,538), followed by metabolic processes (12,322) and single organism processes (11,785). Several other processes, including biological regulation and response to stimulus, also comprised a significant number of transcripts (Fig. 3, biological process). The most prominent molecular functions included binding activity (12,037) and catalytic activity (10,141) (Fig. 3, molecular function). In the cellular component analysis, most transcripts were assigned to cell (12,808), cell part (12,251), organelle (8,806), and membrane (8,272). Macro-molecular complex (5,632), membrane part (5,265), and organelle part (4,717) also had a substantial number of transcripts (Fig. 3, cellular component).

For the KEGG analysis, 17,583 annotated transcripts were mapped to identify the active pathways in C. japonicum at a cut-off E-value < 0.00001. Of these transcripts, 9,418 transcripts had significant matches in the database and were assigned to 137 KEGG pathways. Metabolism had the most unigenes; amino acid metabolism had the highest number of annotated unigenes, followed by carbohydrate metabolism, xenobiotic biodegradation and metabolism, lipid metabolism, biosynthesis of antibiotics, etc. (Table 3). These annotations provide insight into the transcriptome by enhancing our understanding of the specific functions and pathways in C. japonicum.

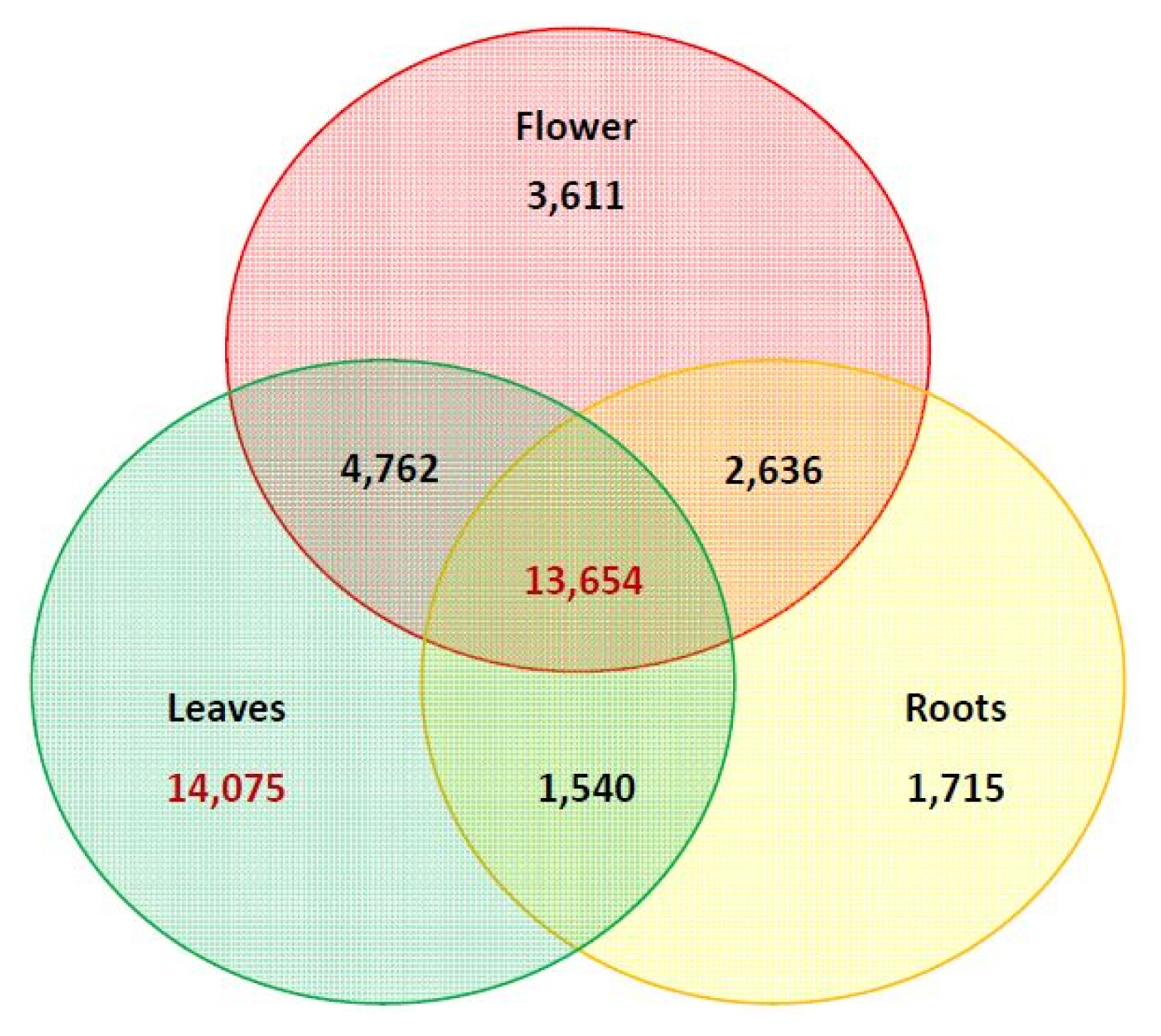

To identify the differentially ex pressed genes, the transcriptome data from C. japonicum leaf, root and flower tissues were analysed using the EdgeR package in R software [19]. The DEGs were visualized as an MA plot (log ratio vs. abundance plot) of flower vs. leaf, flower vs. root and leaf vs. root (Supplementary Fig. 1). The red dots represent transcripts with positive and negative log2fold change values, indicating the up-regulation and down-regulation of the DEGs in each comparison. Using these criteria, most transcripts were mapped in the leaf tissue (34,031), followed by the flower (24,663) and root (19,545) tissues (Table 2). The expression values corresponding to specific genes were arranged in a matrix form, and two tables of the counts and FPKM were generated to represent the genes (data not shown). The count matrix represented the number of reads mapped to the reference, and the FPKM matrix represented the normalized value using the FPKM-based count value. In total, 51,133 expressed reference sequences were obtained. Overall, the leaf (Cjapleaf) samples had the most expressed transcripts (46,991, 91.90%), followed by the flower (Cjapflower) (37,665, 73.66%) and root (Cjaproot) (32,257, 63.08%), as shown in Table 4. Based on the expression differences shown in the Venn diagram in Fig. 4, GO and KEGG analyses were performed again based on the nr database annotations. The unigenes were assigned to 61 GO categories as follows: Cjapleaf vs. Cjaproot (29,491 up-regulated and 27,898 down-regulated unigenes) (Supplementary Fig. 2); Cjaproot vs. Cjapflower (16,365 up-regulated and 32,596 down-regulated unigenes) (Supplementary Fig. 3) and Cjapflower vs Cjapleaf (19,207 up-regulated and 33,472 down-regulated unigenes) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

In the KEGG analysis, 2,615 unigenes were annotated in the Cjapleaf vs. Cjaproot comparison; of these unigenes, 2,115 up-regulated unigenes were assigned to 109 pathways, and 500 down-regulated unigenes were assigned to 113 pathways. In the comparison Cjaproot vs. Cjapflower, 877 unigenes were annotated in the KEGG classification; of these unigenes, 348 up-regulated unigenes were assigned to 103 pathways, and 529 down-regulated unigenes were assigned to 116 pathways. In the comparison Cjapflower vs. Cjapleaf, 934 unigenes were annotated; of these unigenes, 383 up-regulated unigenes were assigned to 97 pathways, and 551 down-regulated unigenes were assigned to 114 pathways. The differences in the expression levels were two-fold or greater, indicating a significant difference between the compared samples. The comparison of the up-regulated and down-regulated transcripts was performed by comparison among the tissues.

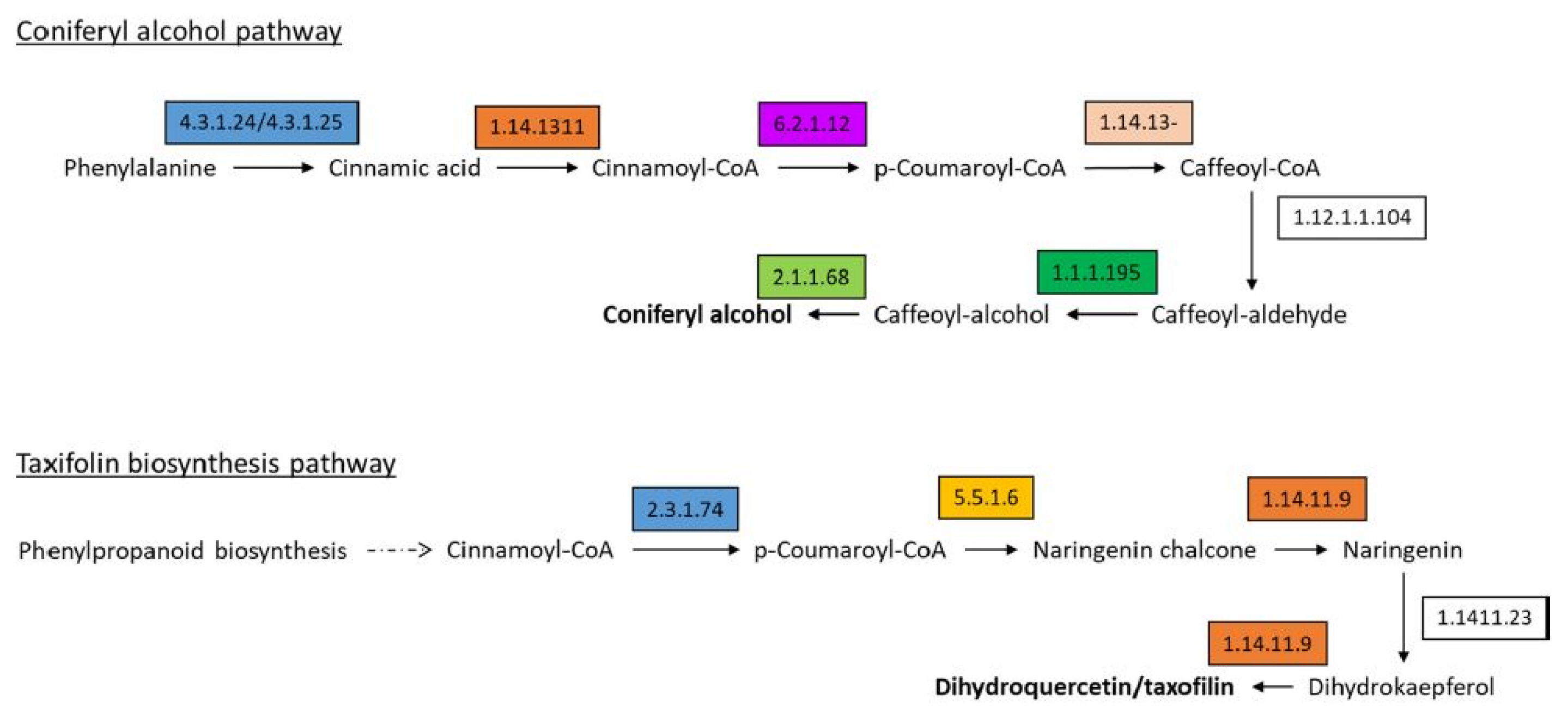

Silybin A and B, iso-silybins A and B, silychristin A, isosilychristin, and silydianin are all collectively called silymarins. Silymarins are the major flavolignans produced in C. japonicum. Taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol are the two major precursors responsible for the production of silymarin [20] and are produced by the flavonoid and phenylpropanoid pathways, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5 (the highlighted boxes represent the enzymes annotated in our data). The unigenes identified for the silymarin production in C. japonicum are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Most enzymes responsible for the production of silymarin were found in all three tissues (flower, leaf, and root) of C. japonicum. Subsequently, silymarin formation occurs via the oxidative radicalization of taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol, followed by a combinational radical coupling [21]. Genes corresponding to the silymarin biosynthetic pathway (flavonoid and phenylpropanoid pathway-related genes) were selected from the C. japonicum transcripts, and the expression patterns were compared among the flower, leaf and root tissues (Supplementary Table 2). The organ-specific gene expression patterns in C. japonicum were confirmed by the heat map technique (Fig. 6). The maximum number of genes was found to be downregulated in leaf tissues.

Cirsium japonicum var. spinossimum is a wild perennial herb that grows in the mountains and fields of Jeju Island, South Korea, and is also found in Japan. This species is often compared to a similar herb called C. japonicum DC [7]. In Korea, this herb is known for its medicinal properties, including its antihaemorrhagic, antihypertensive, antihepatitic, and uretic medicinal properties [2]. Since the advent of next generation technology, this research tool has become important for the generation of vast information regarding genomic and transcriptomic data. These data eventually help infer various basic biological, molecular and cellular processes, especially in non-model organisms and non-sequenced genomes [22–24]. Thus far, no studies have performed a transcriptome analysis of this herb. We characterized the transcriptome of C. japonicum var. spinossimum using an Illumina Hiseq2500. This study represents the first report of the whole transcriptome and differential gene expression among the flower, leaf, and root tissues in C. japonicum var. spinossimum and provides insight into fundamental molecular data.

We obtained 66,078,874 reads after trimming and performing error corrections, and these reads assembled into 51,133 unigenes with an average length of 648 bp (Table 1). The number of mapped transcripts in each tissue was 24,663, 34,031, and 19,545 in the flower, leaf, and root tissues, respectively (Table 2). We obtained unigenes that ranged from 200 to 15,402 bp (Fig. 1), which is comparable to similar RNA-Seq reports [25–27]. This number also represents the high quality of our generated data. Although prior genome information for C. japonicum is lacking, the BLASTX program successfully annotated 33,525 (65.59%) transcripts. The highest similarity obtained with Cynara cardunculus var. scolymus, is a medicinal plant belonging to same family (Asteraceae) [28, 29]. Thus, the C. japonicum transcriptome can prove useful for functional gene studies or molecular biology studies investigating C. japonicum. Of the 17,583 mapped transcripts, the KEGG classification annotated 9,418 (53.56%) transcripts into several pathways (Table 3), but no functional annotation was found for the remaining 46.44% of the assembled unigenes. This might be due to one of the following reasons: either the unigenes matched proteins with unknown functions or they did not have any homologous sequence matches in the database. Thus, these unknown unigenes may be highly important for further research since they may be considered novel transcripts.

The DEG patterns were investigated to further profile the global gene expression differences among the leaf, flower and root in C. japonicum. The most abundant genes were expressed in the leaves, followed by the flowers and roots (Fig. 4). We obtained 26,289 genes that were expressed in all three tissues, including 14,075 genes that were specifically expressed in the leaf tissues, 3,611 genes that were specifically expressed in the flower tissues and 1,715 genes that were specifically expressed in the root tissues. The molecular function category showed that more than 40% of the unigenes were expressed in all three tissues (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). The major categories in which differential gene expression was observed were biological process and cellular components.

Silymarin is a main component in C. japonicum that contributes to its medicinal value. Therefore, we aimed to expand our knowledge by identifying putative unigenes that contribute to the product. Silymarin is reportedly produced via the oxidative coupling of two major precursors, namely, taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol [21]. Most major enzymes responsible to produce both taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol were present in our transcriptome data (Supplementary Table 2), which is consistent with other medicinal plants observed in the same family [6, 20]. In the C. japonicum transcriptome assembly, we identified silymarin biosynthesis-related unigenes (Fig. 5), and their differential expression was assessed (Fig. 6). Compared to their expression in the flower and root tissues, these genes were highly expressed in the leaf tissues. Silymarin biosynthesis has been reported to be lacking in the flower of S. marianum [6].

In addition to these unigenes, unigenes encoding enzymes crucial for the biosynthesis of antibiotics and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites were identified. Medicinal plants represent a rich source of secondary metabolites [30, 31], and their data could be useful for molecular biology research and the mass production of significant metabolites.

This report represents the first de novo assembly of the transcriptome of C. japonicum var. spinossimum obtained from the Korean Peninsula. This study provides resources for comparative transcriptomics, especially in the field of the biochemical and molecular biosynthesis pathways of silymarin. In total, 51,133 unigenes were obtained with a mean length of 648.36 bp. In total, 33,525 annotated sequences were assigned to 64 GO functional groups, and 10,535 unigenes were assigned to 107 KEGG pathways. The DEG analysis revealed that the highest numbers of genes were expressed in the leaf tissues. Candidate genes that might be involved in silymarin biosynthesis may help further functional genomic and transcriptomic analyses in C. japonicum. Putative unigenes that facilitate the production of taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol, which are the major precursors in silymarin biosynthesis, were identified. This work will contribute to the comprehensive knowledge of new traditional medicinal plants for growers and consumers and provides additional characteristics and information regarding the pharmaceutical benefits associated with silymarin biosynthesis.

Supplementary data including two tables and four figures can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.5808/GI.2018.16.4.e34.

Summary of data output from Illumina HiSeq2500 for Cirsium japonicum var. spinossimum

Log2Fold change values obtained for the enzymes involved in Coniferyl alcohol and Taxifolin pathways for Heat map Enzymes for Con niferyl alcohol pathway

MA plot (log ratio vs. abundance plot) for flower vs. leaf, flower vs. root and leaf vs. root in Cirsium japonicum.

Comparison between up-regulated and down-regulated genes based on functional categories in Cirsium japonicum leaf and root tissues.

4-Comparison between up-regulated and down-regulated genes based on functional categories in in Cirsium japonicum flower and root tissues.

Comparison between up-regulated and down-regulated genes based on functional categories in in Cirsium japonicum flower and leaf. tissues

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from 2017 Research Grant, Kangwon National University and the National Institute of Biological resources (NIBR), funded by the Minister of Environment (MOE) of the Republic of Korea (NIBR201626103, NIBR201830101).

Fig. 1

Distribution of the length of the unigenes obtained by the de novo assembly of the transcriptome sequencing in Cirsium japonicum.

Fig. 2

Distribution of the species hits based on the gene annotation of the transcriptome by the BlastX search in Cirsium japonicum var. spinossimum.

Fig. 3

Gene Ontology (GO) annotations of non-redundant consensus sequences. The best hits were aligned to the GO database, and the most consensus sequences were grouped into three major functional categories, namely, biological process, molecular function, and cellular component.

Fig. 4

Venn diagram representing the significantly differentially expressed transcripts among flower, leaf, and root tissues from Cirsium japonicum. The number includes both the up- and down-regulated genes. Genes that are differentially expressed in more than one comparison are depicted in the overlapping area.

Fig. 5

Silymarin is produced via the oxidative coupling of two major precursors, namely, taxifolin and coniferyl alcohol. The figure represents the formation of coniferyl alcohol and taxifolin via the phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathways, respectively. The number in the boxes represents the enzyme as code per the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) classification, and the details are provided in Supplementary Table 2. The coloured boxes represent the enzymes that were found in our transcriptome data.

Fig. 6

Heat map of the differently expressed genes involved in silymarin biosynthesis. Red and green colours indicate up-and down-regulated gene expression, respectively.

Table 1

The total transcripts and length by de novo assembly of RNA sequence data in Cirsium japonicum

| Assembly data | No. |

|---|---|

| Transcripts | 51,133 |

| Total (bp) | 37,533,942 |

| Mean size (bp) | 648 |

| Maximum size | 15,402 |

Table 2

The mapped reads to the transcripts using trimmed RNA sequence data

Table 3

KEGG analysis pathway distribution among the transcriptome of Cirsium japonicum var. spinossimum

References

1. Ge H, Turhong M, Abudkrem M, Tang Y. Fingerprint analysis of Cirsium japonicum DC. using high performance liquid chromatography. J Pharm Anal 2013;3:278–284.

2. Liu S, Luo X, Li D, Zhang J, Qiu D, Liu W, et al. Tumor inhibition and improved immunity in mice treated with flavone from Cirsium japonicum DC. Int Immunopharmacol 2006;6:1387–1393.

3. Federico A, Dallio M, Loguercio C. Silymarin/silybin and chronic liver disease: a marriage of many years. Molecules 2017;22:E191.

4. Loguercio C, Festi D. Silybin and the liver: from basic research to clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:2288–2301.

5. Kim NC, Graf TN, Sparacino CM, Wani MC, Wall ME. Complete isolation and characterization of silybins and iso-silybins from milk thistle (Silybum marianum). Org Biomol Chem 2003;1:1684–1689.

6. Ma Q, Wang LH, Jiang JG. Hepatoprotective effect of flavonoids from Cirsium japonicum DC on hepatotoxicity in comparison with silymarin. Food Funct 2016;7:2179–2184.

7. WoRMS. Cirsium japonicum var. spinosissimum Kitam WoRMS, 2008. Accessed 2018 Nov 1. Available from: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=1157330.

9. Morazzoni P, Bombardelli E. Silybum marianum (Carduus marianus). Fitoterapia 1995;66:3–42.

10. Petrussa E, Braidot E, Zancani M, Peresson C, Bertolini A, Patui S, et al. Plant flavonoids: biosynthesis, transport and involvement in stress responses. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:14950–14973.

11. Nakasugi K, Crowhurst RN, Bally J, Wood CC, Hellens RP, Waterhouse PM. De novo transcriptome sequence assembly and analysis of RNA silencing genes of Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS One 2013;8:e59534.

12. Lehnert EM, Walbot V. Sequencing and de novo assembly of a Dahlia hybrid cultivar transcriptome. Front Plant Sci 2014;5:340.

13. Rastogi S, Meena S, Bhattacharya A, Ghosh S, Shukla RK, Sangwan NS, et al. De novo sequencing and comparative analysis of holy and sweet basil transcriptomes. BMC Genomics 2014;15:588.

14. Wilhelm BT, Marguerat S, Goodhead I, Bähler J. Defining transcribed regions using RNA-seq. Nat Protoc 2010;5:255–266.

15. Martínez-García PJ, Crepeau MW, Puiu D, Gonzalez-Ibeas D, Whalen J, Stevens KA, et al. The walnut (Juglans regia) genome sequence reveals diversity in genes coding for the biosynthesis of non-structural polyphenols. Plant J 2016;87:507–532.

16. Liu MH, Yang BR, Cheung WF, Yang KY, Zhou HF, Kwok JS, et al. Transcriptome analysis of leaves, roots and flowers of Panax notoginseng identifies genes involved in ginsenoside and alkaloid biosynthesis. BMC Genomics 2015;16:265.

17. Lulin H, Xiao Y, Pei S, Wen T, Shangqin H. The first Illumina-based de novo transcriptome sequencing and analysis of safflower flowers. PLoS One 2012;7:e38653.

18. Upadhyay AK, Chacko AR, Gandhimathi A, Ghosh P, Harini K, Joseph AP, et al. Genome sequencing of herb Tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) unravels key genes behind its strong medicinal properties. BMC Plant Biol 2015;15:212.

19. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a bio-conductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010;26:139–140.

20. AbouZid SF, Ahmed HS, Moawad AS, Owis AI, Chen SN, Nachtergael A, et al. Chemotaxonomic and biosynthetic relationships between flavonolignans produced by Silybum marianum populations. Fitoterapia 2017;119:175–184.

21. Lv Y, Gao S, Xu S, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J. Spatial organization of silybin biosynthesis in milk thistle [Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn]. Plant J 2017;92:995–1004.

22. Mudalkar S, Golla R, Ghatty S, Reddy AR. De novo transcriptome analysis of an imminent biofuel crop, Camelina sativa L. using Illumina GAIIX sequencing platform and identification of SSR markers. Plant Mol Biol 2014;84:159–171.

23. Yang Y, Xu M, Luo Q, Wang J, Li H. De novo transcriptome analysis of Liriodendron chinense petals and leaves by Illumina sequencing. Gene 2014;534:155–162.

24. Zhu L, Zhang Y, Guo W, Xu XJ, Wang Q. De novo assembly and characterization of Sophora japonica transcriptome using RNA-seq. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:750961.

25. Zhang X, Allan AC, Li C, Wang Y, Yao Q. De novo assembly and characterization of the transcriptome of the Chinese medicinal herb, Gentiana rigescens. Int J Mol Sci 2015;16:11550–11573.

26. Zhang X, Liu T, Duan M, Song J, Li X. De novo transcriptome analysis of Sinapis alba in revealing the glucosinolate and phytochelatin pathways. Front Plant Sci 2016;7:259.

27. Sun H, Li F, Xu Z, Sun M, Cong H, Qiao F, et al. De novo leaf and root transcriptome analysis to identify putative genes involved in triterpenoid saponins biosynthesis in Hedera helix L. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182243.

28. Acquadro A, Barchi L, Portis E, Mangino G, Valentino D, Mauromicale G, et al. Genome reconstruction in Cynara cardunculus taxa gains access to chromosome-scale DNA variation. Sci Rep 2017;7:5617.

29. Scaglione D, Lanteri S, Acquadro A, Lai Z, Knapp SJ, Rieseberg L, et al. Large-scale transcriptome characterization and mass discovery of SNPs in globe artichoke and its related taxa. Plant Biotechnol J 2012;10:956–969.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 7 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 7,132 View

- 283 Download

- Related articles in GNI