Preliminary Study of Bioinformatics Patents and Their Classifications Registered in the KIPRIS Database

Article information

Abstract

Whereas a vast amount of new information on bioinformatics is made available to the public through patents, only a small set of patents are cited in academic papers. A detailed analysis of registered bioinformatics patents, using the existing patent search system, can provide valuable information links between science and technology. However, it is extremely difficult to select keywords to capture bioinformatics patents, reflecting the convergence of several underlying technologies. No single word or even several words are sufficient to identify such patents. The analysis of patent subclasses can provide valuable information. In this paper, I did a preliminary study of the current status of bioinformatics patents and their International Patent Classification (IPC) groups registered in the Korea Intellectual Property Rights Information Service (KIPRIS) database.

Introduction

There are many ways that research gaps between science and technology can be identified. Bibliographic citation of both academic literature and patent documents is one of the solutions. Unfortunately, patent documents are considerably less accessible [1], compared to academic papers. Whereas vast amount of new information is made available to the public through patents, only a small set of patents are cited in academic papers [2].

Thus, the essential problem arising from citing patents related to bioinformatics is to devise a classification methodology that identifies the relevant patent and only those patents. The suitability of the methodology depends on the purpose of the analysis. However, no single methodology is ideal for identifying patents for a convergence technology, such as bioinformatics. By its nature, it is at the intersection of a number of patent classes.

Accordingly, this paper tentatively employs several methodologies simultaneously to analyze the current status of bioinformatics and to find relevant subclasses, using the Korea Intellectual Property Rights Information Service (KIPRIS, http://www.kipris.or.kr/) patent search system. Initially, a multiple-word search is undertaken of these patents' titles and abstracts. The selected lists are then tabulated, based on International Patent Classification (IPC) subclasses together with some known bioinformatics subclasses. These were then reviewed manually to establish a revised list of bioinformatics patents. These steps have been repeated several times to establish the list of relevant IPC subclasses that appear most frequently in KIPRIS bioinformatics patents.

Outline of Patent Search Methodologies

KIPRIS is an internet-based patent document search service that is available to the public free of charge. Korea Institute of Patent Information has been providing KIPRIS since 1996 on behalf of Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO). It covers publications of Korean Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) applications, legal status information, and trial information. Using the KIPRIS system, the following simple query (documents, containing and the keyword DNA, RNA, and protein, and containing the keyword 'algorithm, database, visualization' in the abstract),

(DNA + RNA + protein + genome) * AB = [algorithm + database + visualization], would retrieve 468 registered patents from the KIPRIS database, as in Fig. 1.

The number of patents can be further reduced by manual screening. Likewise, a common methodology is to undertake keyword searches of the patent title, abstract, or claim, as it is not practical to review the complete claims, specifications, and drawings of related patents.

However, this approach of a pure keyword search has the inherent problem of both including irrelevant patents along with bioinformatics patents and of potentially missing relevant bioinformatics patents. For example, the number of patent documents that have the keyword 'bioinformatics' in the KIPRIS database is 446, as of November 18, 2012. However, the majority of them can not be classified as bioinformatics patents. On the other hand, there is no warranty that actual bioinformatics patents would at least have the keyword 'bioinformatics' in their documents. Nonetheless, this approach illustrates the converging nature of the technologies comprising bioinformatics and represents a good starting point for examining the cross-classification of bioinformatics patents.

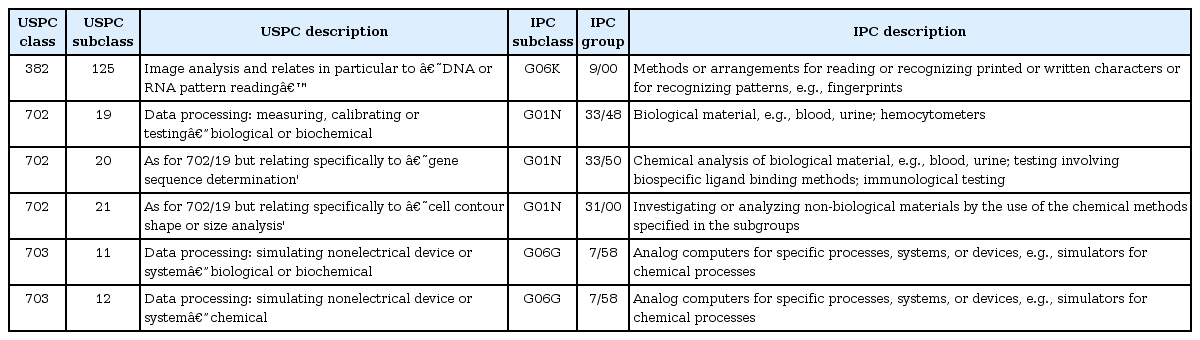

An alternative approach to expand a patent search beyond pure keywords is to include classification information and to use a definition of bioinformatics patents based on several patent subclasses in which bioinformatics patents are expected to be clustered. A good starting point to choose relevant IPC (http://www.wipo.int/classifications/ipc/) bioinformatics classes would be to reference preselected bioinformatics classes. For example, the US Patent Classification (USPC) bioinformatics patent subclasses (382/125, 702/19, 702/20, 702/21, 703/11, and 703/12) suggested in [3, 4] could be used, and they have been mapped into IPC groups G06K 9/00, G01N 33/48, G01N 33/50, G01N 31/00, and G06G 7/58, as in Table 1, by using the USPC-to-IPC reverse concordance system (http://www.uspto.gov/patents/resources/classification/index.jsp).

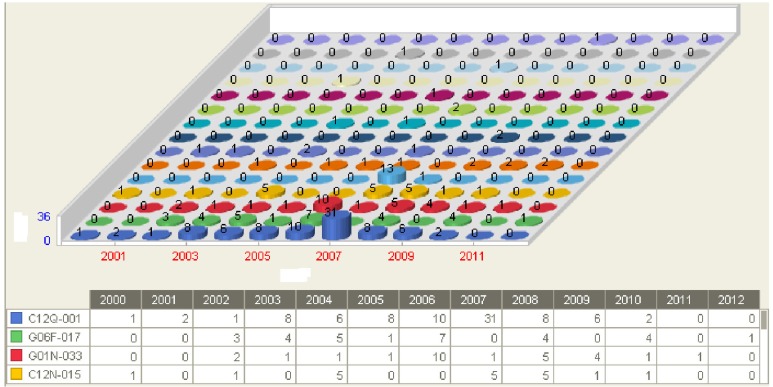

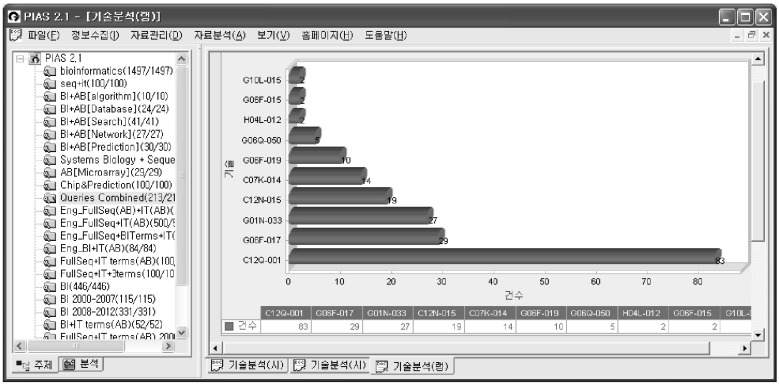

Then, queries using various keywords combined with the groups in Table 1 were initially performed, using the Patent Information Analysis System (PIAS, http://www.kipris.or.kr/kor/add_service/service/service_pias_1.jsp) system, as in Fig. 2. New subclasses or groups linked to bioinformatics can be identified by using various combinations of query terms, as is listed in the left window of Fig. 2. These were then reviewed manually to establish a revised list of bioinformatics patents. These steps were repeated several times to extend the list of relevant IPC groups that appear most frequently in the KIPRIS database. The query terms can be dependent on the characteristics of the intellectual property associated with patents, such as algorithms, data contents, network analysis, and user interfaces.

Combining the results of various queries, using Patent Information Analysis System (PIAS, http://www.kipris.or.kr/kor/add_service/service/service_pias_1.jsp): combining biological keywords (dna? + rna? + "nucleic acid" + protein? + polynucleotid? + nucleotid? + deoxyribonuc? + ribonucleo? + "amino acid" + genom? + proteom? + SNP + "Single Nucleotide Polymorphism" + (metabolic ^2 pathway?) + (signal? ^2 pathway?) + gene + oligonucleotid? + microarray + (DNA ^2 chip?)) with informatics keywords (computer? + software? + program? + algorithm? + data? + protocol? + internet? + interfac? + proteomics + bioinformatics + ((text? + data?) ^2 (Mining? + retrieval?)) + mining? + ontology? + clustering? + statistic? + automat? + visualiz?) in various ways.

The most frequently occurring groups based on the query term containing the keyword 'bioinformatics' in addition to the combination of biological sequence keywords in the abstract was C07K 14/47 (peptides having more than 20 amino acids from mammals), followed by C07K 16/08, C12N 15/11, C12N 15/31, C12Q 1/68, C12N 15/10, G01N 33/68, G06F 17/30, and G06F 19/00. The most frequently occurring groups containing informatics keywords such as visualization, algorithm, software, and database, together with some biological sequences was C12N 15/00 (mutation or genetic engineering; DNA or RNA concerning genetic engineering), followed by C12N 15/63, C12Q 1/68, G01N 33/68, G06F 17/30, and G06F 19/00. The most frequently occurring groups related to database contents or networks was G06F 17/30 (digital computing or data processing equipment or methods, specially adapted for specific functions; information retrieval, database structures therefor).

Combining the results of various queries, I finally selected 213 patents that are most related to bioinformatics. The main groups with the highest frequency were C12Q 001 (measuring or testing processes involving enzymes or micro-organisms) and G06F 017 (digital computing or data processing equipment or methods, specially adapted for specific functions), followed by G01N 033, C12N 015, C07K 014, G06F 019, G06Q 050, H04L 012, G06F 015, and G10L 015. Fig. 3 shows the yearly distribution of these groups.

Conclusion

By identifying the relevant subclasses of bioinformatics patents, the research gaps between science and technology can be identified. In this paper, I did a preliminary study of the current status of bioinformatics patents registered in the KIPRIS database. I identified some of the subclasses and groups related to bioinformatics patents, but the work presented here should be regarded as preliminary, and a more detailed analysis using text-mining techniques will follow in the near future.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank patent attorney, Kwang-Ho Kim at Ewha Womans University, for valuable comments. This work was partially supported by G-SMATT.