Analysis of Gene Expression in Human Dermal Fibroblasts Treated with Senescence-Modulating COX Inhibitors

Article information

Abstract

We have previously reported that NS-398, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)–selective inhibitor, inhibited replicative cellular senescence in human dermal fibroblasts and skin aging in hairless mice. In contrast, celecoxib, another COX-2–selective inhibitor, and aspirin, a non-selective COX inhibitor, accelerated the senescence and aging. To figure out causal factors for the senescence-modulating effect of the inhibitors, we here performed cDNA microarray experiment and subsequent Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. The data showed that several senescence-related gene sets were regulated by the inhibitor treatment. NS-398 up-regulated gene sets involved in the tumor necrosis factor β receptor pathway and the fructose and mannose metabolism, whereas it down-regulated a gene set involved in protein secretion. Celecoxib up-regulated gene sets involved in G2M checkpoint and E2F targets. Aspirin up-regulated the gene set involved in protein secretion, and down-regulated gene sets involved in RNA transcription. These results suggest that COX inhibitors modulate cellular senescence by different mechanisms and will provide useful information to understand senescence-modulating mechanisms of COX inhibitors.

Introduction

Prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase, also called as cyclooxygenase (COX), is an enzyme converting arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2). PGH2 is a common precursor for prostanoid biosynthesis such as PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2, and thromboxane A2. These prostanoids are known to be important chemical mediators for inflammation as well as other biological processes [1]. There are two isoforms of COX. COX-1 (PTGS1) is expressed constitutively in most cells and responsible for basal level of prostanoid biosynthesis. COX-2 (PTGS2) is induced by various stimuli such as bacterial endotoxins, cytokines, genotoxic agents, growth factors, or oncogene products [23].

Most non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are COX inhibitors. These drugs inhibit the COX catalytic activity by occupying the active site of COX. Aspirin, ibuprofen, or flurbiprofen is a non-selective COX inhibitor, which inhibits both COX-1 and COX-2 catalytic activity. In contrast, NS-398, celecoxib, or nimesulide is a selective COX-2 inhibitor, which inhibits COX-2 catalytic activity specifically [34].

The mechanism of aging has not been fully understood. However, it has been proposed that the pro-inflammatory catalytic activity of COX-2 is a causal factor for aging. The hypothesis proposes that reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in the process of normal metabolism or inflammation activate the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB). NF-κB increases the transcription of pro-inflammatory target genes such as COX-2, which in turn stabilizes a chronic inflammatory circuit by generating ROS. This chronic inflammation causes tissue damage and aging [5].

If the pro-inflammatory catalytic activity of COX-2 is a causal factor for aging, COX-2 inhibitors should conceivably inhibit aging. In this context, we have previously examined the effect of COX-2 inhibitors on aging both in the replicative cellular senescence model of human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) and in the intrinsic skin aging model of hairless mice. We observed that among three selective COX-2 inhibitors studied, only NS-398 inhibited the cellular senescence whereas celecoxib and nimesulide accelerated the senescence. In addition, three non-selective COX inhibitors including aspirin, ibuprofen, and flurbiprofen accelerated the senescence [6]. Also, we observed that only NS-398 inhibited the skin aging while celecoxib and aspirin accelerated the skin aging in hairless mice [3]. These studies strongly suggest that the pro-inflammatory catalytic activity of COX-2 is not a causal factor for aging and that the aging-modulating effect of COX inhibitors is attributable to a catalytic activity–independent mechanism.

In an attempt to figure out underlying mechanisms by which COX inhibitors modulate aging, we here performed cDNA microarray experiment and subsequent Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) in HDFs treated with three COX inhibitors, NS-398, celecoxib, and aspirin.

Methods

Materials and cell culture

NS-398 and aspirin were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Celecoxib was a generous gift from Dr. S.V. Yim (Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea). HDFs, isolated from foreskin [7], were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), penicillin (100 units/mL) and streptomycin (100 units/mL) in a 5% CO2 incubator [6].

RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted from HDFs with Trizol (Life Technologies), purified with the addition of chloroform, and precipitated with the addition of isopropanol. The RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometer and the quality of RNA was evaluated by OD 260/280 ratio and gel electrophoresis [8].

cDNA microarray experiment

The following procedures were carried out by Macrogen Co. (Seoul, Korea). Five hundred fifty nanograms of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a T7 oligo(dT) primer. Second-strand cDNA was synthesized, in vitro transcribed, and labeled with biotin-NTP. After purification, 750 ng of labeled cRNA was hybridized to Illumina Human HT12 v.4 bead array (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) for 16-18 h at 58oC. The array signal was detected by using Amersham fluorolink streptavidin-Cy3 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK). Arrays were scanned with an Illumina bead array Reader confocal scanner. Array data were filtered by detection p-value < 0.05 (similar to signal to noise). The average signal values of filtered genes were transformed by logarithm and normalized by the quantile method [8].

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

The beta version of GSEA software and MSigDB 5.2 were downloaded from the Broad Institute (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). GSEA was carried out as described previously [9]. Enrichment of gene sets was considered statistically significant if the normalized p-value was < 0.01 and the false discovery rate (FDR) was < 0.20.

Results

Treatment of HDFs with COX inhibitors

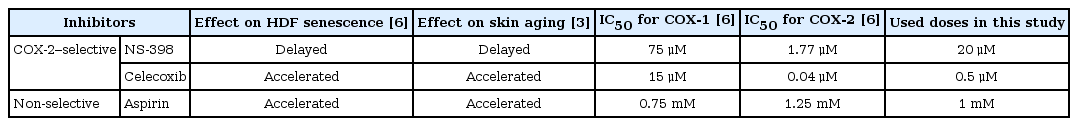

We have previously shown that among COX inhibitors studied, NS-398, a COX-2-selective inhibitor, inhibited replicative cellular senescence in HDFs as well as skin aging in hairless mice, whereas celecoxib, another COX-2-selective inhibitor, and aspirin, a non-selective COX inhibitor, accelerated the senescence and aging. At that time, we treated cells or skin with inhibitors every day for more than a month (Table 1) [36].

To figure out causal factors for the senescence-modulating effect of the inhibitors, we treated HDFs with NS-398, celecoxib, aspirin, or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (the vehicle) every day for only 3 days in this study. The IC50 values have been reported for recombinant human COX-1 and COX-2 of NS-398 and celecoxib [1011], and for recombinant ovine COX-1 and COX-2 of aspirin [12]. In the case of NS-398 and celecoxib, we used approximately 10-fold higher concentration of IC50 to inhibit COX-2 catalytic activity sufficiently. NS-398 and celecoxib showed no acute cellular toxicity at this concentration. In the case of aspirin, however, we used IC50 because 10-fold higher concentration caused acute cellular toxicity (Table 1) [6].

DNA microarray and GSEA

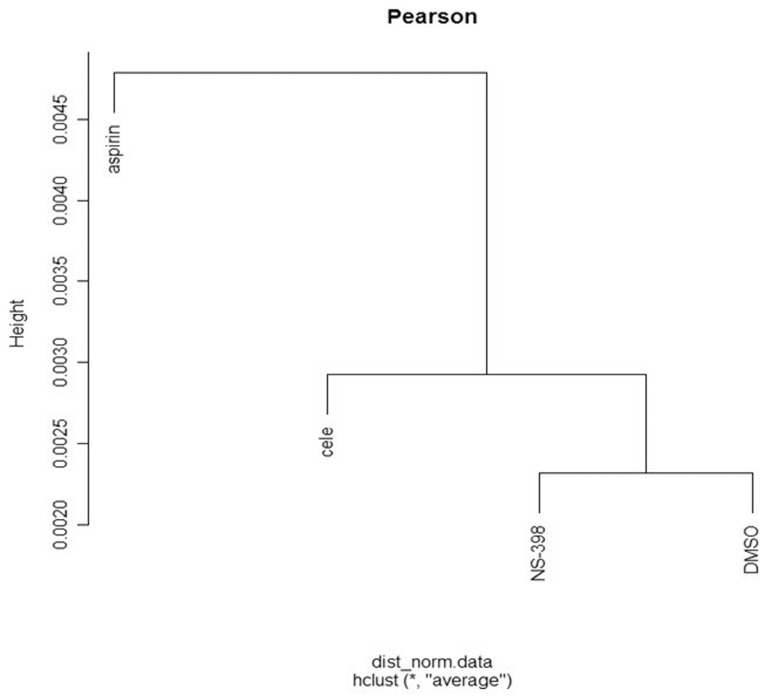

We performed cDNA microarray experiment using RNA extracted from the drug-treated HDFs. Among 47,319 probe sets, 20,271 probe sets passed the criteria of the detection p-value < 0.05. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis showed that drug-treated cells were well segregated in the order of DMSO, NS-398, celecoxib, and aspirin (Fig. 1).

Segregation between the drug-treated HDFs. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis was done between four drug-treated HDFs using 20,271 probe sets with the detection p-value < 0.05.

To figure out underlying mechanisms by which COX inhibitors modulate senescence, we performed GSEA using 17,777 probe sets having all information including gene symbols and gene descriptions. We sorted the data sets based on the value of (INS-398 – IDMSO) for the comparison of NS-398 versus DMSO; the value of (ICelecoxib – IDMSO) for the comparison of celecoxib versus DMSO; and the value of (IAspirin – IDMSO) for the comparison of aspirin versus DMSO to rank the data sets as described previously [9].

We then tested (1) the Hallmark gene sets (H); (2) gene sets regulating canonical pathways—i.e., Biocarta gene sets (C2:CP:BIOCARTA), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene sets (C2:CP:KEGG), and Reactome gene sets (C2:CP:REACTOME); and (3) gene ontology gene sets—i.e., biological process gene sets (G5:BP), cellular component gene sets (G5:CC), and molecular function gene sets (G5:MF).

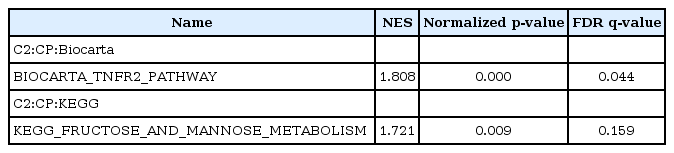

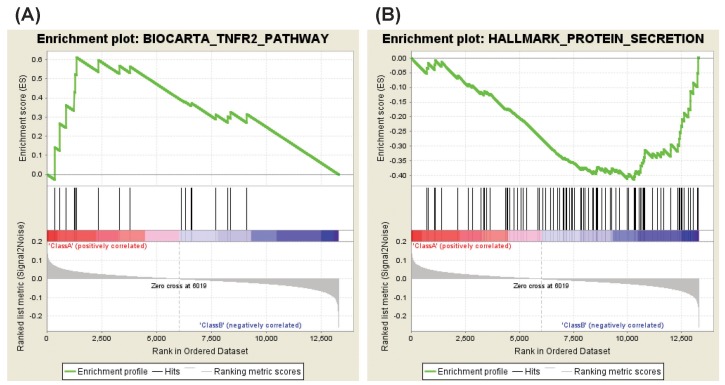

NS-398 versus DMSO

The analysis of NS-398 versus DMSO showed that two gene sets are enriched in NS-398–treated HDFs as compared with DMSO-treated HDFs. These gene sets consist of genes regulating the tumor necrosis factor beta receptor (TNFR2) pathway and the fructose and mannose metabolism (Table 2, Fig. 2A). Enriched genes in each pathway were shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Enrichment plots (NS-398 vs. DMSO). (A) A representative enriched gene set in NS-398–treated HDFs. (B) A representative enriched gene set in DMSO-treated HDFs. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; HDF, human dermal fibroblast.

On the other hand, four gene sets were enriched in DMSO-treated HDFs as compared with NS-398–treated HDFs: genes down-regulated in response to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and genes regulating the protein secretion, the trefoil factor pathway and the receptor-regulated Smads (R-SMAD) binding (Table 3, Fig. 2B). Enriched genes in each gene set were shown in Supplementary Tables 3, 4, 5, 6.

Celecoxib versus DMSO

The analysis of celecoxib versus DMSO showed that four gene sets were enriched in celecoxib-treated HDFs as compared with DMSO-treated HDFs. These gene sets consist of genes involved in the G2M checkpoint, E2F targets, γ tubulin complex and the four way junction (Holliday junction) DNA binding (Table 4, Fig. 3A). Enriched genes in each gene set were shown in Supplementary Tables 7, 8, 9, 10.

Enrichment plots (celecoxib vs. DMSO). (A) A representative enriched gene set in celecoxib–treated HDFs. (B) The representative enriched gene set in DMSO-treated HDFs. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; HDF, human dermal fibroblast.

On the other hand, one gene set was enriched in DMSO-treated HDFs as compared with celecoxib-treated HDFs. This gene set consists of genes regulating olfactory signaling pathway (Table 5, Fig. 3B). The list of enriched genes in this pathway was shown in Supplementary Table 11.

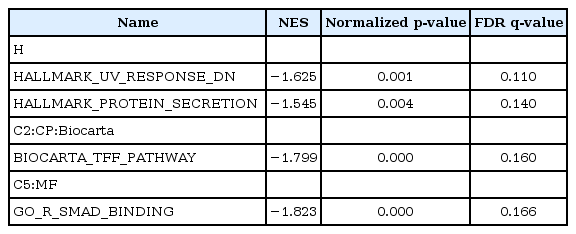

Aspirin versus DMSO

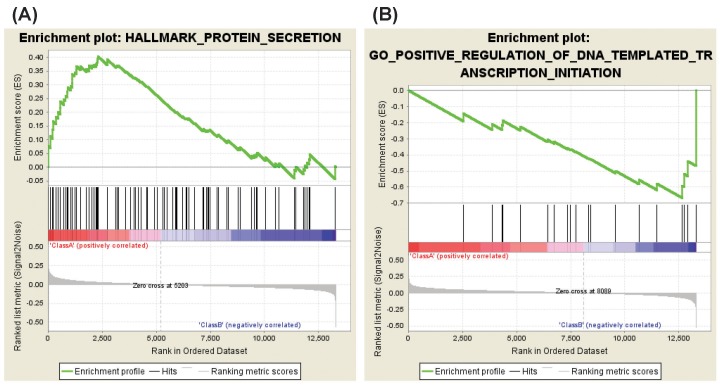

In the case of aspirin versus DMSO, four gene sets were enriched in aspirin-treated HDFs as compared with DMSO-treated HDFs. These gene sets consist of genes involved in the protein secretion, keratin filament and intermediate filament, and genes down-regulated in response to UV radiation (Table 6, Fig. 4A). Enriched genes in each gene set were shown in Supplementary Tables 12, 13, 14, 15.

Enrichment plots (aspirin vs. DMSO). (A) A representative enriched gene set in aspirin-treated HDFs. (B) A representative enriched gene set in DMSO-treated HDFs. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; HDF, human dermal fibroblast.

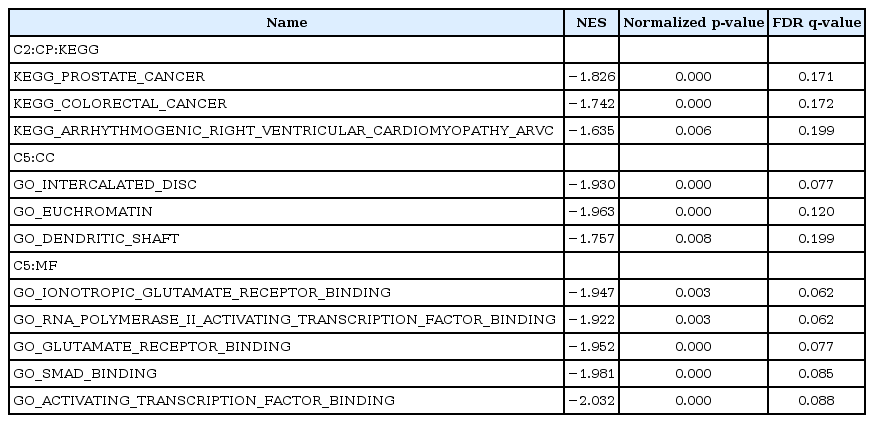

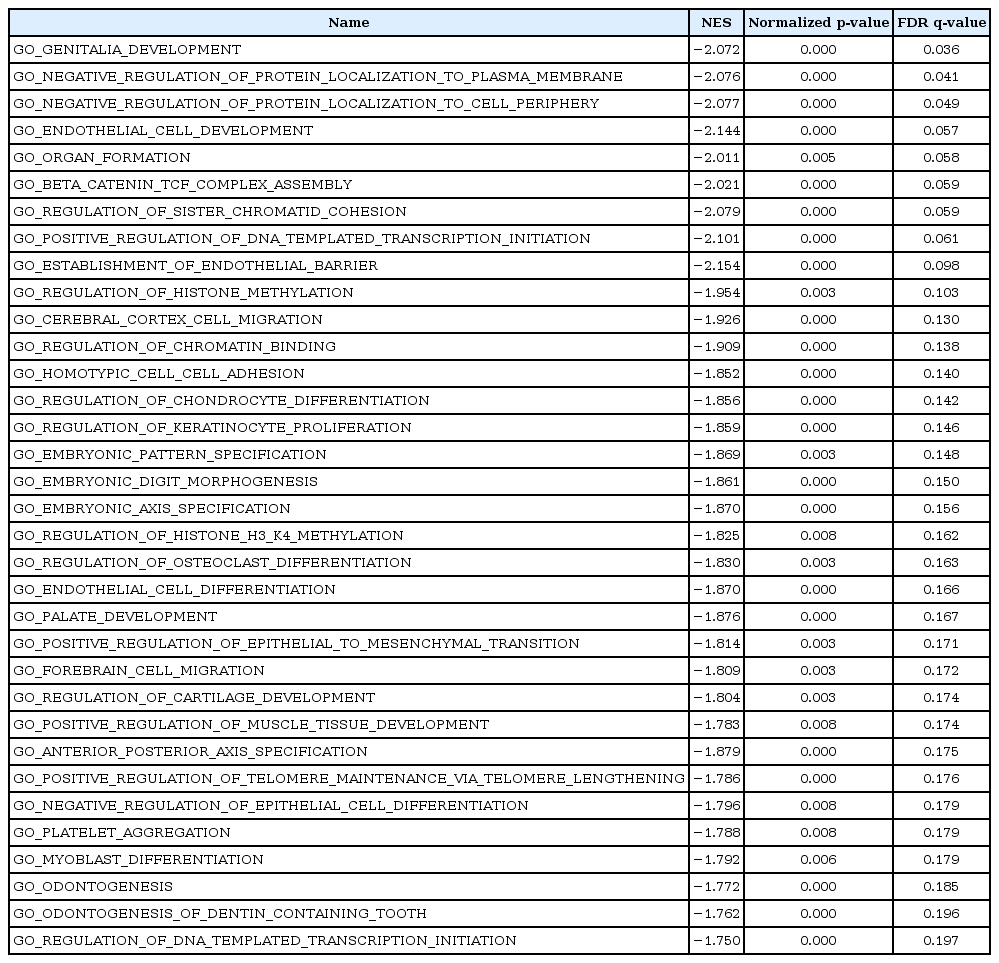

On the other hand, three gene sets of C2:CP were enriched in DMSO-treated HDFs as compared with aspirin-treated HDFs: genes regulating prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and cardiomyopathy (Table 7). In addition, 34 gene sets of C5:BP, three gene sets of C5:CC and five gene sets of C5:MF were enriched in DMSO-treated HDFs as compared with aspirin-treated HDFs. These gene sets consist of genes involved in embryonic development, negative regulation of protein localization to plasma membrane, DNA-dependent RNA transcription, cell differentiation, glutamate receptor binding, or Smad binding (Tables 7 and 8, Fig. 4B). Of note, the gene set involved in platelet aggregation was enriched in DMSO-treated HDFs as compared with aspirin-treated HDFs (Table 8, FDR, 0.179). Enriched genes in representative gene sets were shown in Supplementary Tables 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22.

Discussion

Our data showed that NS-398 treatment up-regulated the gene set involved in the TNFR2 pathway (Table 2, Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table 1). This pathway is well known to activate the NF-κB signaling that mediates cell proliferation, anti-apoptosis, inflammation, differentiation, or development (Supplementary Fig. 1) [13]. NF-κB, a transcription factor, has been reported to regulate cellular senescence though its role in the senescence is controversial. Overexpression of c-Rel resulted in premature senescence in normal human keratinocytes [14]. On the contrary, mouse embryonic fibroblasts from NF-κB1 knockout mice showed enhanced cellular senescence [15]. In addition, siRNA against NF-κB2 or RelB induced premature senescence in HDFs in a p53-dependent manner [16]. These studies suggest that the anti-senescent effect of NS-398 might be attributable to a regulation of NF-κB signaling.

NS-398 treatment also up-regulated the gene set involved in the fructose and mannose metabolism (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). This metabolic pathway leads to enhanced glycolysis and N-glycan biosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Alterations of glucose metabolism have been reported in cellular senescence though the data is conflicting. In human mammary epithelial cells, B-Raf–induced premature senescence was associated with a reduction of glucose uptake, and overexpression of hexokinase 2 prevented the oncogene-induced senescence [17]. On the contrary, glucose consumption and hexokinase activity were increased in senescent HDFs as compared to young HDFs [18]. These studies suggest that NS-398 might delay cellular senescence via regulation of glycolysis.

It is intriguing that the gene set involved in protein secretion is down-regulated by NS-398 treatment but is up-regulated by aspirin treatment (Tables 3 and 6, Figs. 2B and 4A, Supplementary Tables 4 and 12). It has been reported that cellular senescence is accompanied by an increase in the secretion of intercellular signaling molecules including interleukins, chemokines, growth factors, proteases, and extracellular matrix proteins [1920]. For example, production of interleukin-1, -6, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-1, -2, -3, -7, -8, -12, -13, -16, -20, -26, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand-1, -2, -4, -5, -6, -8, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7, connective tissue growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte colony stimulating factor, matrix metalloproteinase-1, -3, -10, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, or fibronectin increased in senescent HDFs as compared to in young HDFs [21]. Ectopic expression of chemokine receptors such as CXCR1 or CXCR2 induced premature senescence in HDFs [22]. Extracellular matrix from young HDFs restored senescent HDFs to an apparently youthful state [23]. In addition, there is a report that p16-induced senescence is accompanied by an increase in the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mouse and human pancreatic beta cells [24]. These studies suggest that regulation of protein secretion might be an important common mechanism by which NS-398 delays but aspirin accelerates cellular senescence.

In addition to the up-regulation of protein secretion, aspirin down-regulated gene sets involved in DNA-dependent RNA transcription (Table 7, FDR, 0.062 and 0.088; Table 8, FDR, 0.061 and 0.197; Fig. 4B). Compatible with these results, a cDNA microarray study reported that genes involved in transcription were down-regulated specifically during senescence in HDFs [25]. In addition, there is a report that RNA transcription was decreased in aged rat brain as compared to in young rat brain [26]. Therefore, aspirin might accelerate cellular senescence by downregulation of DNA-dependent RNA transcription.

It is well known that aspirin inhibits platelet aggregation and thereby thrombus formation [27]. Consistent with this, our data showed that the gene set involved in platelet aggregation was down-regulated by aspirin treatment (Table 8, FDR, 0.179).

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) are categorized into two families, that is, the Ink4 family including p15, p16, p18, and p19, and the Cip/Kip family including p21, p27, and p57. It has been reported that these CKIs are actively involved in cellular senescence. For example, ectopic expression of p15, p16, p19, p21, or p27 was reported to induce premature senescence in HDFs [2829]. According to our data, celecoxib treatment up-regulated gene sets relating G2M checkpoint and E2F targets (Table 4, Fig. 3A). In addition, CDKN1B encoding p27 and CDKN2C encoding p18 were enriched in both gene sets (Supplementary Table 7, Running enrichment score [ES], 0.410 and 0.274; Supplementary Table 8, Running ES, 0.299 and 0.193). These data suggest that celecoxib might accelerate cellular senescence through up-regulation of CKIs.

Collectively, our results suggest that COX inhibitors modulate cellular senescence by different mechanisms though they have the anti-catalytic activity commonly. We believe that our study will provide useful information to understand senescence-modulating mechanisms of COX inhibitors.

References

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including 22 tables and two figures can be found with this article online https://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-15-56-s001.pdf.

Supplementary Fig. 1

BIOCARTA_TNFR2_PATHWAY. Enriched genes were highlighted in orange color.

Supplementary Fig. 2

KEGG_FRUCTOSE_AND_MANNOSE_METABOLISM. Enriched genes were highlighted in orange color.

Supplementary Table 1

Enriched genes of BIOCARTA_TNFR2_PATHWAY in NS-398–treated HDFs (NS-398 vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 2

Enriched genes of KEGG_FRUCTOSE_AND_MANNOSE_METABOLISM in NS-398–treated HDFs (NS-398 vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 3

Enriched genes of HALLMARK_UV_RESPONSE_DN in DMSO-treated HDFs (NS-398 vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 4

Enriched genes of HALLMARK_PROTEIN_SECRETION in DMSO-treated HDFs (NS-398 vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 5

Enriched genes of BIOCARTA_TFF_PATHWAY in DMSO-treated HDFs (NS-398 vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 6

Enriched genes of GO_R_SMAD_BINDING in DMSO-treated HDFs (NS-398 vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 7

Enriched genes of HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT in celecoxib-treated HDFs (celecoxib vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 8

Enriched genes of HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS in celecoxib-treated HDFs (celecoxib vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 9

Enriched genes of GO_GAMMA_TUBULIN_COMPLEX in Celecoxib-treated HDFs (celecoxib vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 10

Enriched genes of GO_FOUR_WAY_JUNCTION_DNA_BINDING in celecoxib-treated HDFs (celecoxib vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 11

Enriched genes of REACTOME_OLFACTORY_SIGNALING_PATHWAY in DMSO-treated HDFs (celecoxib vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 12

Enriched genes of HALLMARK_PROTEIN_SECRETION in aspirin-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 13

Enriched genes of HALLMARK_UV_RESPONSE_DN in aspirin-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 14

Enriched genes of GO_KERATIN_FILAMENT in aspirin-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 15

Enriched genes of GO_INTERMEDIATE_FILAMENT in aspirin-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 16

Enriched genes of KEGG_PROSTATE_CANCER in DMSO-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 17

Enriched genes of KEGG_ARRHYTHMOGENIC_RIGHT_VENTRICULAR_CARDIOMYOPATHY_ARVC in DMSO-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 18

Enriched genes of GO_GENITALIA_DEVELOPMENT in DMSO-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 19

Enriched genes of GO_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_PROTEIN_LOCALIZATION_TO_PLASMA_MEMBRANE in DMSO-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 20

Enriched genes GO_ENDOTHELIAL_CELL_DEVELOPMENT in DMSO-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 21

Enriched genes of GO_RNA_POLYMERASE_II_ACTIVATING_TRANSCRIPTION_FACTOR_BINDING in DMSO-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)

Supplementary Table 22

Enriched genes of GO_SMAD_BINDING in DMSO-treated HDFs (aspirin vs. DMSO)