DNA Methylation Profiles of Blood Cells Are Distinct between Early-Onset Obese and Control Individuals

Article information

Abstract

Obesity is a highly prevalent, chronic disorder that has been increasing in incidence in young patients. Both epigenetic and genetic aberrations may play a role in the pathogenesis of obesity. Therefore, in-depth epigenomic and genomic analyses will advance our understanding of the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying obesity and aid in the selection of potential biomarkers for obesity in youth. Here, we performed microarray-based DNA methylation and gene expression profiling of peripheral white blood cells obtained from six young, obese individuals and six healthy controls. We observed that the hierarchical clustering of DNA methylation, but not gene expression, clearly segregates the obese individuals from the controls, suggesting that the metabolic disturbance that occurs as a result of obesity at a young age may affect the DNA methylation of peripheral blood cells without accompanying transcriptional changes. To examine the genome-wide differences in the DNA methylation profiles of young obese and control individuals, we identified differentially methylated CpG sites and investigated their genomic and epigenomic contexts. The aberrant DNA methylation patterns in obese individuals can be summarized as relative gains and losses of DNA methylation in gene promoters and gene bodies, respectively. We also observed that the CpG islands of obese individuals are more susceptible to DNA methylation compared to controls. Our pilot study suggests that the genome-wide aberrant DNA methylation patterns of obese individuals may advance not only our understanding of the epigenomic pathogenesis but also early screening of obesity in youth.

Introduction

Obesity is a disorder defined by excessive adiposity. Given that approximately 3 million people die due to complications from being overweight each year worldwide, the steadily increasing number of overweight individuals will pose a major threat to public health [1]. Notably, the prevalence of obesity in children has increased in recent years, and addressing childhood obesity has become one of the major challenges in the field of public health.

In addition to a number of modifiable risk factors, including the social and cultural environment of an individual, certain genetic factors can contribute to an increased susceptibility to obesity. Genome-wide association studies have identified several candidate genomic variants on the LEP (leptin), IGF2, and POMC genes [23]. However, such variants are observed in only a minority of obese individuals, leaving a majority of obese people without the identification of causal genomic factors [4]. Moreover, some studies failed to identify a strong association between the development of obesity in children and in their parents [56]. Thus, the causal role of genetics in the etiology of childhood obesity is unclear, suggesting that non-genetic factors, including behavioral or environmental ones, should be taken into account.

Recently, the role of epigenetic regulation in the pathogenesis of multifactorial disorders, including obesity, has been recognized [7]. With the advent of high-throughput DNA methylation profiling technologies, it is now possible to discover novel genes and markers for the early screening and accurate diagnosis of obesity on a genome-wide scale. For example, Wang et al. [8] compared the DNA methylation profiles obtained from the peripheral blood cells of seven young obese and seven normal individuals using the Illumina HumanMethylation27 BeadChip Kit, with a resolution of ~27,000 CpG sites. They identified a number of potential markers (e.g., CpG sites located at the promoters of UBASH3A and TRIM3) that showed differential methylation between obese and control individuals and subsequently validated the loci with pyrosequencing. Almen et al. [9] used the same chip to identify DNA methylation markers associated with both age and obesity. Since these genome-wide studies have mainly focused on marker discovery, in-depth genomic analyses (e.g., exploration of the relationship between differentially methylated CpG sites and other genomic features or gene expression) are still largely uninvestigated.

In this study, we performed genome-wide DNA methylation and transcriptome profiling of young obese individuals compared with healthy controls (n = 6 for both groups) to examine whether changes in DNA methylation or gene expression in peripheral blood cells could distinguish obese individuals from controls. For methylation profiling, we used the methylation microarray with the highest resolution currently available—the Illumina HumanMethylation450 platform, with a resolution of ~485,000 CpG sites—to ensure proper genomic correlative analyses. Recognizing that DNA methylation can be used as a predictive marker for obesity, we next performed genomic correlative analyses of the DNA methylation patterns obtained during profiling to identify enrichment patterns of CpG sites that were differentially methylated between obese and control individuals with respect to genes, CpG islands (CGIs), and epigenomic compartments. The putative functions of those genes harboring the differentially methylated CpGs were also investigated.

Methods

Patient and control samples

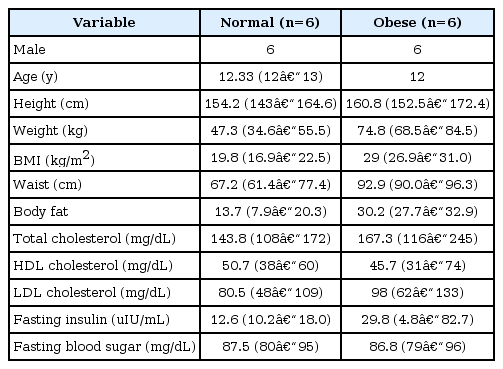

The subjects in this study were selected from a cohort that was part of a community-based prevention and management program of childhood obesity in a rural area of Korea (Chungju, Chungcheongbuk-do). Twelve participants, six obese children with a high body mass index and six children with a normal body weight, were randomly selected for this pilot study (Table 1). All individuals were 12–13 years old, male and had an East Asian ancestry. Since the subjects of this study were minors, informed consent for all individuals was obtained in written format both from the participants and their parents. This study, including the consent procedure, has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (KIRB-00524-010) at The Catholic University of Korea, College of Medicine.

DNA methylation and expression profiling

The samples for DNA methylation and gene expression profiling experiments were prepared as follows. Blood from each individual was collected into two EDTA tubes (3 mL). After the contents had been sufficiently mixed for 5 min, the tubes were stored in a refrigerator. The genomic DNA and total RNA were extracted using DNeasy and RNeasy Blood and Tissue Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA was carried out using an EZ DNA methylation kit from Zymo Research (Irvine, CA, USA), and DNA methylation profiles were generated using the Illumina HumanMethylation450 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Background correction and dye bias equalization were conducted using methylumi and lumi packages in R, respectively. Then, the data was normalized using the beta mixture quantile method [10]. The methylation levels of individual CpG sites were estimated as beta-values, which are the ratio of intensities between locus-specific methylated and unmethylated bead-bound probes. For statistical analysis, the DNA methylation level at each CpG site was converted to an M-value using the logit transformation as recommended by Du et al. [11] and Marabita et al. [12]. The probes annotated as NCBI's reference SNP ID (rs ID) numbers were removed, then the methylation status of a total of 485,512 CpG sites were used for the analysis.

Genome-wide gene expression levels were measured using an Illumina Human HT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip Kit, with 47,318 probes. The extraction of raw data and the subsequent preprocessing were performed using the Illumina GenomeStudio software according to the manufacturer's instructions. The obtained expression profiles were then quantile normalized using the R preprocessCore package. The DNA methylation and DNA expression profile datasets were submitted to ArrayExpress (accession numbers E-MTAB-3757 and E-MTAB-3753, respectively). DNA and RNA from 12 subjects were loaded onto a single 12-well chip for methylation and gene expression analyses, respectively, so that batch effect adjustment did not need to be considered.

Unsupervised clustering

Hierarchical clustering for both gene expression and DNA methylation was carried out using the R package. Euclidean distance was used as a distance metric, and single-linkage clustering was adopted. For gene expression profiles, highly variable genes were selected using the mean absolute deviation, and clustering analyses were conducted using these 1,000 selected genes.

Statistical analysis

Hypermethylated and hypomethylated CpG sites identified in each sample were partitioned using a Gaussian mixture model [13], based on the distribution of the M-values in each sample. For each sample, the Expectation-Maximization algorithm was run 100 times with different seed values, and the model with the largest likelihood value was chosen as the best-fit model within the 100 experiments. Then, the hyper methylated and hypomethylated CpG sites in each sample were assigned by selecting the component with the bigger corresponding posterior probability. The analyses were performed using the R mixtools package [14]. The differentially methylated CpG sites and the differentially expressed genes were identified using the empirical Bayes model implemented in the limma package [15].

Chromatic region identification

Chromatin statuses were obtained from ChromHMM results [16], coordinated using human genome build 37 (hg19), which was downloaded from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) as a Browser Extensible Data (BED) format. The chromatin state at the differentially methylated CpG sites was determined by finding overlaps with the regions defined in the dataset given in the software.

Results

Differences in DNA methylation and gene expression patterns between obese and normal individuals

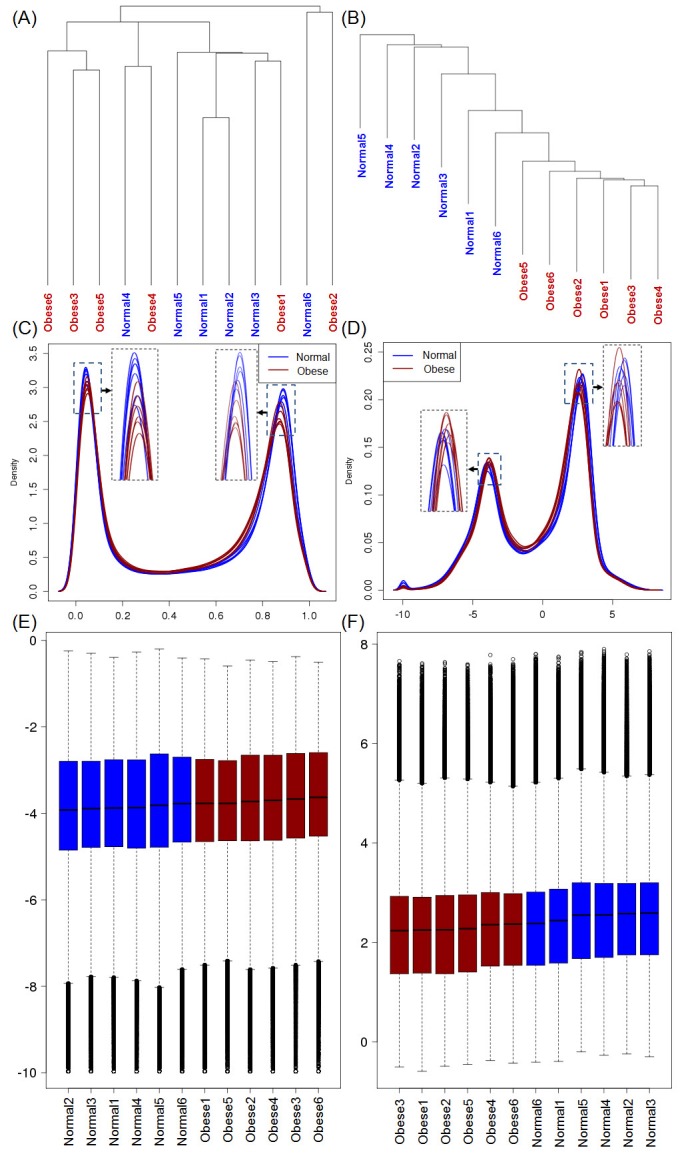

We first investigated whether gene expression levels and/or DNA methylation profiles can distinguish obese individuals from control individuals with normal body weights (n = 6 in each group). To this end, we performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering analyses using gene expression profiles. No clear segregation was observed between the obese and control individuals using the gene expression profiles (Fig. 1A). In contrast to gene expression, hierarchical clustering using DNA methylation profiling revealed a unique cluster of obese individuals that was segregated from the controls (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the obese individuals may harbor characteristic epigenetic marks in their blood cells. We next investigated the global distribution of DNA methylation levels of all CpG sites examined across the 12 individuals. The distribution of beta-values (Fig. 1C) showed a bimodal distribution whose two peaks correspond to the hypomethylated and hypermethylated CpG sites. After transforming the beta-values to M-values (Fig. 1D), we divided the DNA methylation sites into hypomethylated and hypermethylated CpG sites using the Gaussian mixture model. Boxplots of M-values corresponding to hypomethylated and hypermethylated CpG sites are shown for each sample in Fig. 1E and 1F, respectively. Of note, when sorted by median value, a clear segregation of obese individuals from controls was observed in both profiles. M-values representing hypomethylated CpG sites skewed higher for obese individuals compared with controls, and the resulting shift in median values was responsible for the segregation of obese and control individuals (p ≈ 0.0 for all normal vs. all obese; one-tailed t test) (Fig. 1E). In addition, the hypermethylated CpG sites of obese individuals tended to have lower M-values compared to controls (p ≈ 0.0 for all obese vs. all normal; one-tailed t test) (Fig. 1F). The overall M-value distribution between obese and control individuals suggests that the difference in methylation between two groups may be subtle, but our analyses revealed the CpG sites in obese individuals may have less frequent hypomethylation and hypermethylation compared to controls.

Distribution of DNA methylation profiles. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the expression of genes (A) and the DNA methylation patterns (B) in obese (Obese 1–6) and control individuals (Normal 1–6). (C) The distribution of beta-values is shown across 12 individuals (red and blue for obese and control individuals, respectively). Left and right insets are magnified as views of peaks representing hypomethylated and hypermethylated CpG sites, respectively. (D) The distribution of M-values represented in a similar manner to that shown in panel C. (E) Boxplot of hypomethylated CpG sites shown across 12 individuals. The cases are sorted in order of the median of M-values. (F) Hypermethylated CpG sites are represented in a similar manner to that shown in panel E.

The extent of DNA methylation varies across the genome

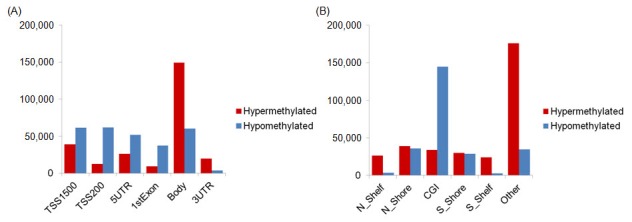

To investigate the level of CpG methylation with respect to nearby genes or CGIs, we categorized the CpG sites into six regional categories: the 3′ untranslated region (UTR), 5′ UTR, first exon, gene body, TSS200, and TSS1500. TSS200 and TSS1500 represent the 200 bp and 1,500 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site (TSS), respectively. We also categorized CpG sites as follows: CGIs (i.e., those belonging to CGIs), CGI shore and shelf (i.e., those located in the <2 kb flanking a CGI and the <2 kb flanking outward from a CpG shore, respectively), and ‘other.’ North (N) and south (S) indicate upstream and downstream of the CGI, respectively. Fig. 2A and 2B show the number of hypermethylated and hypomethylated CpG sites, as distinguished by M-values, in six gene-based and five CGI-based CpG categories.

Distribution of hypermethylated and hypomethylated CpG sites with respect to nearby genes and CpG islands (CGIs). (A) The numbers of hypermethylated and hypomethylated CpG sites are shown for six gene-based CpG categories. (B) CGI-based CpG categories are represented in a similar manner to that shown in panel A. The y-axis is the summation of the CpG sites across all individuals. TSS1500, 1,500 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; TSS200, 200 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; UTR, untranslated region; CGI, CpG island.

We calculated the ratio of hypermethylated to hypomethylated CpG sites, which was defined as the number of hypermethylated CpG sites divided by the number of hypomethylated CpG sites (Supplementary Fig. 1). It should be noted that the ratio of hypermethylated to hypomethylated CpG sties varied markedly in all individuals with respect to the genomic contexts, i.e., the previously described gene-based (0.20–5.54) and CGI-based (0.23–8.66) regional categories. The genomic regions near TSSs, including the 5′ UTR, first exon, and TSS200, were mainly dominated by hypomethylated CpG sites (the ratios were 0.51, 0.24, and 0.20, respectively). By contrast, the CpG sites at the gene body and 3′ UTR regions were usually hypermethylated (the ratios were 2.47 and 5.54, respectively). Moreover, CGIs were usually hypomethylated (the ratio was 0.23), but the 5′ and 3′ CGI shelf regions were hypermethylated (the ratios were 7.87 and 8.66, respectively). The observed overall pattern of DNA methylation with respect to nearby genes or CGIs agrees well with previous reports: CpG sites at promoters with active transcription have less DNA methylation compared to downstream compartments such as the gene body, and CpG sites at CGIs are relatively free from methylation.

The genomic and epigenomic landscape of differentially methylated CpG sites in obesity

We next identified the CpG sites differentially methylated between obese and control individuals. A total of 6,041 differentially methylated CpG sites were identified to have a significance level of p < 0.001. The false discovery rate (FDR) was 0.08 when the Benjamini-Hochberg method was applied to adjust the p-values. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows a Manhattan plot for the log-transformed significance levels of all CpG sites investigated.

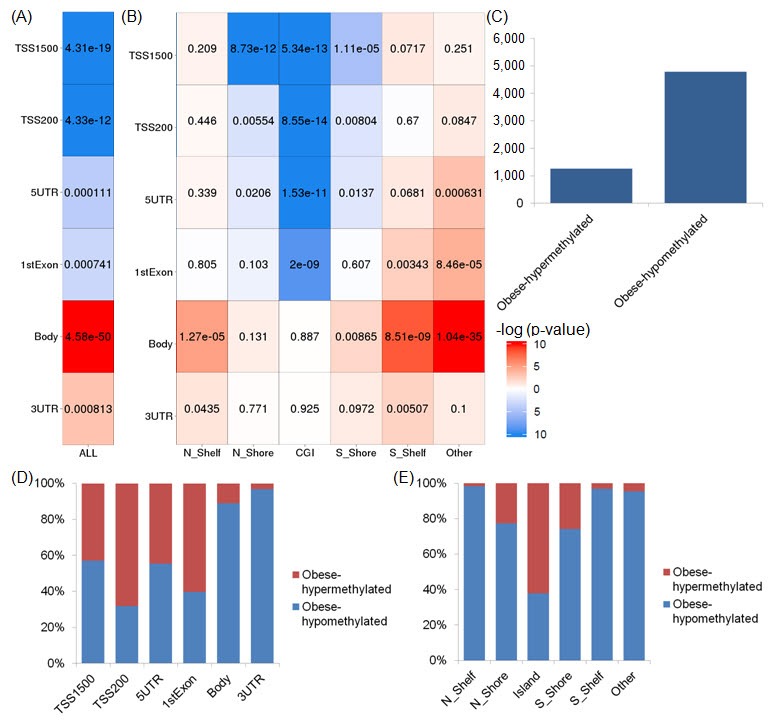

Fig. 3A shows an uneven distribution of differentially methylated CpG sites with respect to the six gene-based CpG categories. The over- and under-representation of differentially methylated CpG sites was observed in gene body, TSS200, and TSS1500 regions (p = 4.6 × 10−50, p = 4.33 × 10−12, and p = 4.33 × 10−19, respectively). When the genomic context of CGIs was taken into account (Fig. 3B), a relative deficit of differentially methylated CpG sites in the nearby TSS regions was observed in CGIs, while the enrichment of differentially methylated CpG sites in the gene body was observed at regions distant from CGI (i.e., CGI shelves and others).

Genomic contexts for the differentially methylated CpG sites. (A) A plot showing the proportions of the differentially methylated CpG sites across gene-based categories. The p-value was estimated using Fisher's exact tests. Red and blue colors represent the relative over- and under-representation of differentially methylated CpG sites in each of the genomic regions. (B) Shown in relation to the CpG islands (CGIs) in each genomic region. (C) The numbers of obese-hypermethylated and obese-hypomethylated CpG sites identified from the differentially methylated sites are shown. (D) The proportions of obese-hypermethylated and obese-hypomethylated CpG sites are shown with respect to nearby genes. (E) The same proportions are shown with respect to CGI-based categories. TSS1500, 1,500 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; TSS200, 200 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; UTR, untranslated region.

Next, we divided the differentially methylated CpG sites into hypermethylated and hypomethylated sites in obese children. We annotated them as ‘obese-hypermethylated and obese-hypomethylated CpGs’ to distinguish them from the hypomethylated/hypermethylated CpG sites identified in individual M-value profiles. We observed a dominance of obese-hypomethylated CpG sites (79.1%; 4,779 sites) over obese-hypermethylated CpG sites among all of the differentially methylated CpG sites (Fig. 3C). We then investigated the relative ratio of obese-hypermethylated to obese-hypomethylated CpG sites in gene-based and CGI-based regional categories (Fig. 3D and 3E). The majority of differentially methylated CpG sites in the gene body and 3′ UTR regions were obese-hypomethylated CpG sites (the ratios of obese-hypermethylated/obese-hypomethylated CpG sites in these regions were 0.13 and 0.03, respectively) (Fig. 3D). On the other hand, the differentially methylated sites in the genomic regions near the TSS, such as the TSS200 and first exon regions, were mainly composed of obese-hypermethylated CpG sites (the ratios were 2.14 and 1.52, respectively) (Fig. 3D). A dominance of obese-hypermethylated CpG sites was also noted in CGI regions (the ratio was 1.64), whereas CpG sites in CGI-shelf regions were largely obese-hypomethylated (the ratio was 0.02) (Fig. 3E). Of note, 70.8% of obese-hypermethylated CpG sites were found in CGIs.

Next, we categorized the differentially methylated CpG sites according to 15 different chromatin states, as described in the ChromHMM software [16]. Given the tissue-specific epigenetic configurations, we elected to use the annotation dataset of lymphoid origin (from the GM12878 lymphoblastoid cell line) as the profile that best matched ours. We first observed that the differentially methylated CpG sites were overrepresented mainly on transcribed regions (Fig. 4A). The p-values were 2.91 × 10−3, 1.63 × 10−11, and 8.31 × 10−16 for the 9_Txn_Transition (transcription transition), 10_Txn_elongation (transcription elongation) and 11_Weak_Txn (weak transcription) regions, respectively (Fisher's exact test). It was also observed that promoter and enhancer regions were largely depleted of differentially methylated CpG sites. In particular, all promoter-related states represented in the first three state categories (1_Active_Promoter, 2_Weak_Promoter, and 3_Poised_Promoter) showed underrepresentation for the differentially methylated CpG sites (Fig. 4A). That is, as we observed in the genomic regional abundance analysis, the differentially methylated CpG sites were mainly found at the genomic regions marked for active transcription. When the differentially methylated CpG sites were categorized into obese-hypermethylated and obese-hypomethylated CpG sites (Fig. 4B), a majority of the differentially methylated CpG sites in transcribed and promoter-related regions were obese-hyper- and obese-hypomethylated CpG sites, respectively. For instance, 96.6% of CpG sites in active promoter regions, as well as 95.7% and 62.4% of CpG sites at poised promoter and weak promoter, respectively, were obese-hypermethylated CpG sites. In contrast to the promoter regions, 95.7% of the differentially methylated CpG sites in transcriptional regions, annotated in ChromHMM as transcriptional transition, elongation, or weak transcription, showed lower DNA methylation levels in obese children.

Chromatin state enrichment at the differentially methylated regions. (A) The proportions of chromatin states for the differentially methylated CpG sites compared to all CpG sites. The value was calculated as the ratio of the number of CpGs on the chromatin states among the total differentially methylated CpGs divided by the ratio of chromatin states among all CpGs. p-values from Fisher's exact tests are shown at the upper side on each bar. (B) Proportions of obese-hypermethlylated and obese-hypomethylated CpG sites are shown across 15 chromHMM-annotated chromatin states.

Functional relationships between DNA methylation markers and obesity

We next identified 21 genes with significant enrichment of differentially methylated CpG sites in the obese children (Fisher's exact test; p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The CpG sites in the enriched genes were mainly obese-hypomethylated and located mostly in the gene body region, which was expected given the overall distribution of differentially methylated CpG sites. We further investigated the extent of differential expression of these genes between the obese and control individuals using the same statistical method as was used for the identification of the differentially methylated CpG sites (R limma package; see Methods). However, none of these 21 genes showed significantly differential expression (unadjusted p < 0.001). Supplementary Table 1 lists the significance level for the differential expression of 18 of the 21 genes; excluded are MIR1185-2, FLJ39609, and CELA2A, with no expression values available. Although one gene, ZNF154, with obese-hypermethylation at TSS200 showed a slight downregulation in expression (unadjusted p < 0.05), most cases showed no clear relationship between gene expression and CpG methylation. One possible explanation for this observation is that the differentially methylated CpG sites at the enriched genes were mainly located in the gene body, the methylation of which is not always associated with the expression of the genes, in contrast to the methylation of regulatory regions such as gene promoters. In this exploratory study, we focused on the identification of differentially methylated CpG sites that may be able to distinguish young obese individuals from young normal individuals; the association between gene expression and CpG methylation, as well as their early diagnostic potential, requires further investigation.

Lastly, we investigated the potential relationship between the observed genes with significant enrichment of differentially methylated CpG sites and the pathogenesis of obesity based on previously published studies. Among the genes with differentially methylated CpG sites, ZNF154 encodes a member of the zinc finger protein family, which are transcriptional regulators of adipogenesis [17]. POLR3E encodes DNA-directed RNA polymerase III subunit RPC5, and it is known that the loss of MAF, which is a repressor of RNA polymerase III, affects resistance to obesity [18]. Although the direct effects of SDK1, which encodes sidekick cell adhesion molecule 1, on obesity are unknown, some studies have investigated the relationships between cellular adhesion molecules and obesity [19]. KIAA0146 is a scaffolding protein involved in DNA repair, and it has been reported that DNA damage or DNA repair deficiency may be associated with obesity [20]. GPR125 encodes a membrane protein that belongs to the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Previous studies have revealed that G protein-coupled receptors may serve as therapeutic targets for obesity and type 2 diabetes [21]. CAPS2 encodes a calcium-binding protein and may function in the regulation of the secretion of insulin [22]. RNF213 encodes a ring finger protein, which is a specialized type of zinc finger protein. A study found the depletion of RNF213 increased glucose tolerance in mice [23]. CELA2A belongs to the chymotrypsin-like elastase family, and a relationship between neutrophil elastase and insulin resistance has been previously reported [24]. Given that some of the genes harbor more frequent than expected differentially methylated CpG sites have been previously implicated in the metabolic disorders, further investigation of these genes and their role in childhood obesity is required.

Discussion

In this study, we carried out the microarray-based profiling of DNA methylation and gene expression in peripheral white blood cells obtained from obese and normal children. We investigated whether the DNA methylation or gene expression profiles (1) are distinct between the young obese individuals and controls, (2) show unique enrichment patterns of hyper-vs-hypomethylated CpG sites with respect to nearby genes or CGIs, and (3) whether such enrichment patterns are also observed for CpG sites that are differentially methylated between young obese individuals and controls.

We first examined whether the gene expression or DNA methylation profiles could be used to distinguish the obese individuals from the normal control individuals. Unsupervised clustering of the DNA methylation profiles segregated the obese individuals from controls, suggesting that the young obese individuals harbor epigenetic marks in their peripheral blood cells that are distinct from those of normal controls. For marker selection, we further performed leave-one-out-cross-validation, k-nearest neighborhood (k-NN) method-based marker selection, and predictive modeling. For 12 rounds of iterations, we selected the top 100 differentially methylated sites using the empirical Bayes approach and predicted the phenotypes of the selected cases. However, we did not achieve a good classification accuracy using jackknife approaches for cross-validation for the gene expression datasets or the DNA methylation profiles. The results imply that obesity cannot be completely predicted by a small number of candidate biomarkers. Instead, our genome-wide analyses showed that there are aberrant DNA methylation patterns in obese children compared to normal children.

Abnormal DNA methylation patterns have been observed in wide variety of human diseases. Certain studies suggest that abnormal DNA methylation patterns in some of these diseases include the loss of DNA methylation on gene bodies and the gain of DNA methylation on gene promoter CGIs, which is by and large the opposite of the normal physiological methylation pattern found in the human genome [2526]. Our analyses revealed that the majority of the differentially methylated CpG sites are those with relative hypomethylation in obese children. Such obese-hypomethylated CpG sites were overrepresented in gene body regions and represented one of the major epigenetic alterations in the blood cells of young obese individuals. In addition, our results implied that regulatory CpG sites near TSS in obese individuals tended to be relatively hypermethylated compared to controls. This observation was further validated by the evaluation of chromatin status using chromHMM data, where the combined analyses showed relative hypermethylation of regulatory regions (active, weak, and poised promoters) but hypomethylation of transcribed regions (those annotated as transcription transition, elongation, or weak transcription) in obese individuals compared to controls.

When we searched for differentially expressed genes using the same criteria as those used for the differentially methylated CpG sites, a relatively small number of genes with a p < 0.001 and a corresponding FDR of 0.91 were identified (Supplementary Table 2). Given the fact that the expression-based k-NN predictive model failed to identify obese individuals, the gene expression profiles may not serve as appropriate biomarkers of obesity in youth. However, we found that some of the top-ranked genes were also related to epigenetic regulation. For example, histone deacetylases (HDACs) are related to insulin sensitivity, and HDAC inhibition can be a treatment for diabetes. Moreover, since HDAC2 can directly bind to DNMT1, a widely expressed DNA methyltransferase that plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation patterns [27], the change in HDAC2 expression may be related to the aberrant DNA methylation patterns we observed in obese individuals.

Our pilot study provides a line of evidence for the importance of epigenomic characteristics in investigating childhood obesity and also the potential utility of such markers for the early diagnosis of obese children. Blood represents a mixture of multiple types of cells, the composition of which has been reported to vary between obese and lean individuals. For example, through analysis of blood cell fractions, a study verified that DNA methylation in B cell and natural killer lymphocytes is altered in obese subjects [28]; other studies have reported similar results [2930]. The cellular heterogeneity and the differing number of blood cell counts between individuals could affects DNA methylation analysis [31]. Thus, further investigation of the DNA methylation profiles, with consideration of the cell heterogeneity in blood, may lead to a clearer understanding of the epigenomic differences in obese children.

To date, a number of genome-wide studies have presented associations between inherited germline variants and metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes and obesity. However, a majority of patients still lack clarity on the causal, heritable factors underlying their disease, suggesting that there are still many limitations to overcome for these germline markers to be practically used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes. Measuring the alterations in DNA methylation profiles detectable in blood as a minimally invasive biological resource may be useful not only in understanding the epigenomic effects on obesity, but also in providing critical insight and clinical applications for the early detection of obesity. However, our findings were obtained from a relatively small cohort (n = 6), so the statistical power was limited. Thus, the interpretation of the results from our pilot study requires caution. Further investigation to ascertain the clinical impact of our results is needed in a larger, independent cohort of young obese individuals. Additional studies integrating genetic and epigenetic information could unveil clues that deepen our understanding of the pathogenesis of obesity and that help to improve the diagnostic and prognostic markers for use in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the R&D Program of the Society of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, & Future Planning (NRF-2013M3C8A2A02078507).

References

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including two tables and three figures can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-15-28-s001.pdf.

Supplementary Table 1

Expression comparison of genes with significant enrichment of differentially methylated CpGs

Supplementary Table 2

Differentially expressed genes

Supplementary Fig. 1

Hyper-vs.-hypomethylated CpGs ratio with respect to nearby genes and CGIs. (A) The hyper-vs.-hypo-methylated CpGs are shown for six gene-based CpG categories. (B) Similarly shown for CGI-based CpG categories. The y-axis is calculated as the number of the hypermethylated CpGs divided by the number of hypomethylated CpGs. TSS1500, 1,500 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; TSS200, 200 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; UTR, untranslated region; CGI, CpG island.

Supplementary Fig. 2

Manhattan plot for the significance of the differentially methylated CpG sites. Blue line represents the significance level or p-value of 0.001.

Supplementary Fig. 3

Genes significantly enriched with CpGs differentially methylated between obese and control individuals. The number in each cell is the number of the differentially methylated CpGs in the corresponding genomic region. Red and blue represent obese-hypermethylated and obese-hypomethylated CpGs, respectively. TSS1500, 1,500 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; TSS200, 200 bp regions upstream of the transcription start site; UTR, untranslated region.