Mining the Proteome of Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum ATCC 25586 for Potential Therapeutics Discovery: An In Silico Approach

Article information

Abstract

The plethora of genome sequence information of bacteria in recent times has ushered in many novel strategies for antibacterial drug discovery and facilitated medical science to take up the challenge of the increasing resistance of pathogenic bacteria to current antibiotics. In this study, we adopted subtractive genomics approach to analyze the whole genome sequence of the Fusobacterium nucleatum, a human oral pathogen having association with colorectal cancer. Our study divulged 1,499 proteins of F. nucleatum, which have no homolog's in human genome. These proteins were subjected to screening further by using the Database of Essential Genes (DEG) that resulted in the identification of 32 vitally important proteins for the bacterium. Subsequent analysis of the identified pivotal proteins, using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Automated Annotation Server (KAAS) resulted in sorting 3 key enzymes of F. nucleatum that may be good candidates as potential drug targets, since they are unique for the bacterium and absent in humans. In addition, we have demonstrated the three dimensional structure of these three proteins. Finally, determination of ligand binding sites of the 2 key proteins as well as screening for functional inhibitors that best fitted with the ligands sites were conducted to discover effective novel therapeutic compounds against F. nucleatum.

Introduction

Fusobacterium nucleatum is a gram-negative anaerobic bacterium which plays vital role in the architecture of oral biofilms. This dominant oral bacterium is very much associated with periodontitis, a very common infectious disease worldwide. F. nucleatum also affects some other bodily infections such as peritonsillar abscesses, endocarditis, skin ulcers, and septic arthritis [1234]. Coincidentally, it may cause severe infections in a child's body. In many studies, F. nucleatum is appeared to be related with preterm birth and has been found in the placenta, amniotic fluid, and chorioamnionic membranes of women delivering ahead of time. Preterm birth is the leading cause of child mortality and morbidity, accounting for 7% to 11% of all births in the United States alone [5]. Moreover, many studies have linked F. nucleatum with colorectal cancer; in addition, a mechanism has been reported by which F. nucleatum promotes colonic tumor formation without following the usual mechanism of instigating colonic inflammation or otherwise irritating the colon tissue and thereby demonstrating a direct and specific colonic carcinogenesis [67].

Appropriate antibiotic therapy and surgical drainage constitute the basis for treating fusobacterial infections. However, the emergence of multidrug resistant strains of F. nucleatum has made it difficult to guide the choice of empiric treatment. The first case of resistance to penicillin by fusobacteria was reported in the mid-1980s. There is evidence of an increased frequency of β-lactamase production by fusobacteria [8]. The incidence of widespread resistance of Fusobacterium spp. to erythromycin and other macrolides has been reported as well [9]. Though antibiotics like clindamycin, chloramphenicol, carbenicillin, cefoperazone, cefamandole [10], and amoxicillin [11] are shown to be active against this pathogen, ever evolving antibacterial resistance [12], chances of cross resistance [13], and the associated untoward effects of antibiotics [14] persistently urge the researchers to explore more promising and safer drug targets. More importantly, increasing evidence of association between Fusobacterium and colorectal cancer has even more intensified this urge.

In this context, this study aimed to explore some potential novel drug targets other than the aforementioned targets. We have adopted an approach focusing on two important criteria. Firstly, the identified target protein should be indispensable for the survival of the pathogen. Secondly, the target protein should not be homologous to any protein of the human proteome. The nonhomolog property of these target proteins check the chance of the cross-reaction with the human host and thus ascertains highly selective therapeutic targets. This may facilitate minimizing the adverse reactions of the prospective drug [15]. In this way, we have identified some potential drug targets which are not only human non-homologous essential proteins in unique metabolic pathway of the pathogen but also circumvent the resistant mechanism of current targets [16]. Moreover, we have predicted the three dimensional (3D) structure of these target proteins and analyzed ligand binding sites and corresponding ligands of the best proteins to facilitate the search for novel drugs which might potentially arrest the growth of F. nucleatum.

Methods

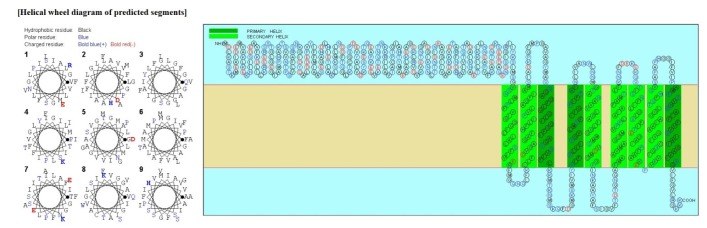

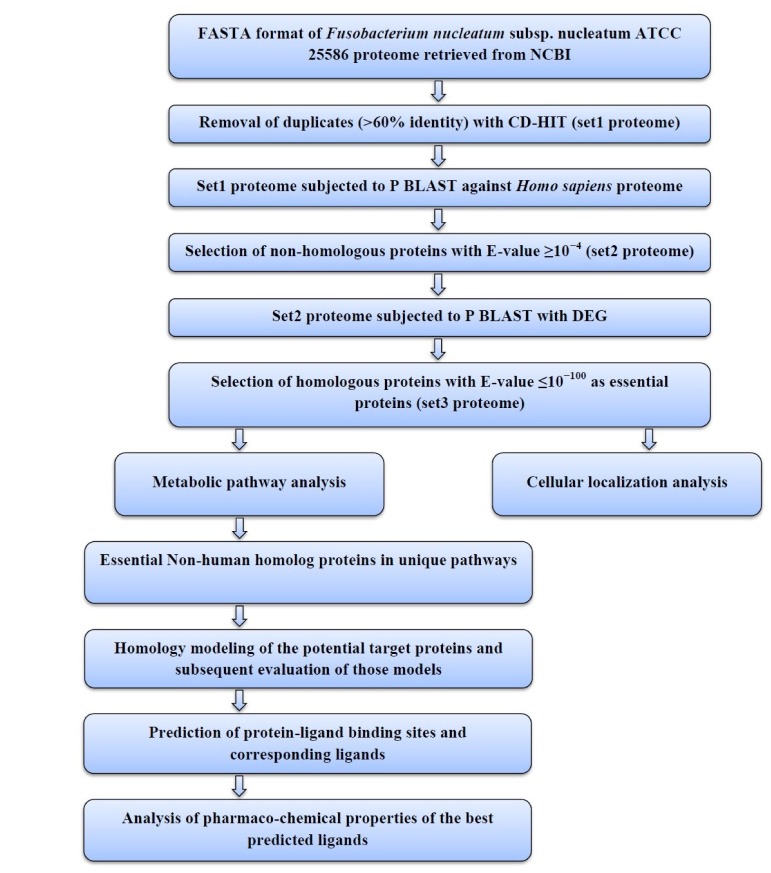

The sequential diagram to identify and to characterize the putative drug targets of Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum ATCC 25586 is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Flowchart. A schematic representation of process analysis and interpretations. FASTA, FAST alignment; CD-HIT, Cluster Database at High Identity with Tolerance; P BLAST, Protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; DEG, Database of Essential Genes.

Retrieval of the proteome of F. nucleatum

The complete proteome of F. nucleatum was retrieved in FAST alignment (FASTA) format from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

CD-HIT analysis

The proteins were subjected to Cluster Database at High Identity with Tolerance (CD-HIT) analysis (http://weizhong-lab.ucsd.edu/cdhit_suite/cgi-bin/index.cgi) [17]. The program takes a FASTA format sequence database as input and produces a set of non-redundant, representative sequences as output. The process was carried out with a sequence identity cutoff of 0.6, thus eliminating redundant sequences with more than 60% identity [181920]. The resultant proteins were grouped as Set1 proteome.

Elimination of human homologous proteins of F. nucleatum

Protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTP) analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was carried out for the Set1 proteome against the proteome of Homo sapiens. Proteins with an E-value (expectation value) 10–4 were eliminated; assuming that they have a certain level of homology with the host genome [21]. The resultant data set (Set2 proteome) of F. nucleatum had no homology with the human proteome.

Identification of non-human homologous essential proteins in F. nucleatum

Then the Set2 proteome was subjected to BLASTP analysis with Database of Essential Genes (DEG; http://tubic.tju.edu.cn/deg/), which contains all the essential genes currently available. An E-value of 10–100 was set as the cutoff value [22]. Thus, a Set3 proteome of F. nucleatum was obtained by grouping the proteins that showed an E-value 10–100. Set3 proteome contains the proteins of F. nucleatum that could be considered as novel drug targets because they are not present in the host and are involved in essential metabolic functions in the bacterium.

Metabolic pathway analysis

The human non-homologous essential proteins of F. nucleatum obtained through BLASTP were then subjected to metabolic pathway analysis, which was done by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS; http://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/) [23] at KEGG [24]. The server provides functional annotation of genes by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) comparisons against the manually curated KEGG GENES database. The result contains KEGG Orthology (KO) assignments and automatically generated KEGG pathways.

Unique pathway identification

After this, unique metabolic pathways of Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum ATCC25586 were identified through the comparison of metabolic pathways of both Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum ATCC25586 and Homo sapiens by using KEGG Genome Database [25]. Among unique metabolic pathways of only those proteins were identified which were human non-homologue essential proteins.

Sub-cellular localization of unique essential metabolic proteins

The program PSORTb V.3.0 (http://www.psort.org/psortb/index.html), CELLO (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/), and SOSUI (http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/sosui_submit.html) server was used to characterize whether the proteins are soluble or trans-membrane in nature. This computational tool illustrates where the protein resides in the cell. So if the protein is associated with the cell membrane, there is more possibility that it can be highlighted as a potential therapeutic target [2627].

Homology modelling ofunique essential metabolic proteins

To predict the 3D structure of unique essential metabolic proteins, homology modelling was done by the server Protein Homology/Analogy Recognition Engine (Phyre2). The retrieved amino acid sequence in FASTA format was used as input data in Phyre2 (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index). In this respect, the intensive mode of protein modeling was selected in order to get an accurate model.

Model refinement

Homology based modeling often contain significant local distortions, including steric clashes, unphysical phi/psi angles and irregular H-hydrogen bonding networks, which render the structure models less useful for high-resolution functional analysis. Refinement of structures could be a solution of this problem [28]. To refine the predicted model Mod-Refiner (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/ModRefiner/); an algorithm for atomic-level, high-resolution protein structure refinement is used.

Verification and validation of the predicted 3D model

To check the accuracy of the predicted 3D structures, Protein Data Bank Summary (PDBsum; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thorntonsrv/databases/pdbsum/Generate.html) was used [29]. The PDBsum generated result was further subjected to documentation analysis by PROgram to CHECK the stereochemical quality of protein structures (PROCHECK) [30]. ERRAT algorithm (http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/ERRAT/) helps in the assessment of the protein structure. Verify 3D (http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/Verify_3D) Structure Evaluation Server was used for 3D profiling of the residue. Qualitative Model Energy Analysis (QMEAN; http://swissmodel.expasy.org/qmean/cgi/index.cgi) was also done which is a composite scoring function that derives both global and local error estimates on the basis of one single model. Global error is estimated for entire structure and local one for per residue error.

Prediction of ligand binding sites and corresponding ligands

Once the final model of our best considered predicted proteins was built, the possible ligand binding sites and their corresponding ligands were revealed using COACH (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/COACH/), a meta-server approach which uses BioLip database for predicting protein-ligand binding site [31].

Verification of the pharmaco-chemical properties of the best predicted ligands

The pharmaco-chemical properties of the best predicted ligands were retrieved from the DrugBank Database (http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/) to demonstrate them as potential inhibitors of the best considered target proteins.

Results

Among a total of 4,630 proteins of Fusobacterium nucleatum strain ATCC 25586, 2,639 proteins were nullified. In effect, we found 1,991 proteins as non-paralogous. BLASTP screening of these proteins against the Homo sapiens genome results in 1,499 proteins which were non-homologous to human proteome.

Furthermore, the 1499 host non-homologous proteins were then screened through DEG with an E-value cutoff score of 10–100 revealing 32 essential proteins. The DEG houses the records of presently available essential genes of a number of organisms.

With a view to identify the metabolic function of 32 essential proteins, metabolic pathway was analyzed by KAAS server at KEGG identifying a set of 30 proteins as putative drug targets. After that, comparative metabolic pathway analysis of human host and F. nucleatum was performed at KEGG Genome Database [3233]. This comparison reveals 12 unique pathways which are present exclusively in F. nucleatum and among those 12 pathways 3 non-human homologous essential proteins were found to be present on two different unique pathways. The results are shown in Table 1. Two out of three metabolic proteins are involved in phosphotransferase system (PTS) and one protein is known to incorporate in peptidoglycan biosynthesis.

Results of subtractive genomic and metabolic pathway analysis for Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum ATCC 25586

Psortb and CELLO, the two bacterial protein subcellular localization prediction tools, demonstrated that these three proteins locate in the cytoplasmic membrane and thereby implying these proteins to be promising drug target site. The server SOSUI discriminates whether the proteins are soluble or membranous. Two proteins were soluble namely phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase, PTS system fructose-specific IIABC component, and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase was trans-membrane protein (Table 2, Fig. 2).

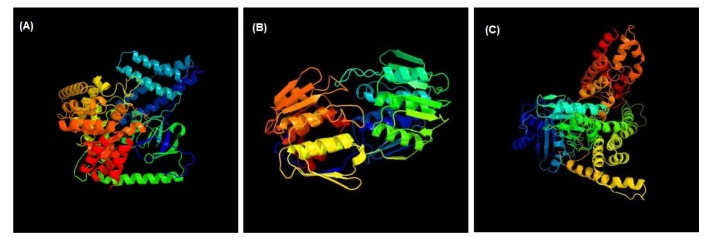

3D structures of the three unique and essential metabolic proteins were obtained by homology modeling using Phyre2 (Fig. 3).

Homology modeling of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase (A), UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase (B), and phosphotransferase system fructose-specific IIABC component (C).

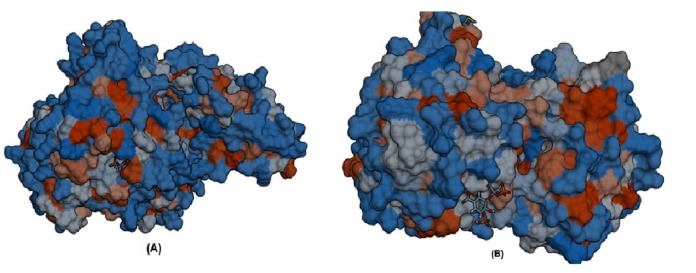

ModRefiner derived refined model (Fig. 4) of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase were analyzed. In case of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase in initial model the percent of residues in favored region were 91.0% whereas 92.1% in the final model. Though in case of N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase amino acids residue in favored region were same in both the initial and final model but has a change in disallowed region, initially disallowed region had 0.5% residues and after refinement it narrowed down to 0.0%.

ModRefiner derived model of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase (A) and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase (B).

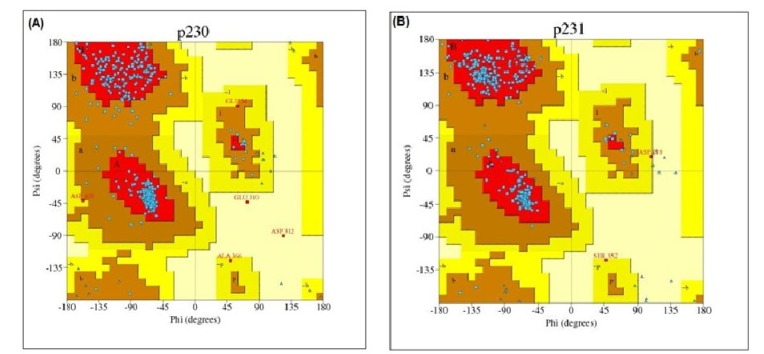

After that, PROCHECK was used to measure the stereo-chemical quality of protein models at a resolution of 1.8. PROCHECK renders information about the protein chains and stereo-chemical properties such as Ramachandran plot quality, peptide bond planarity, bad non-bonded interactions, main chain hydrogen bond energy, C alpha chirality and overall G factor [34]. Ramachandran plot regarding this analysis is shown in Fig. 5.

Ramachandran plot of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase (A) and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase (B).

Moreover, verification of the refinement was performed by Errat, QMEAN server, and Verify 3D. Errat is particularly appropriate for assessing the progress of crystallographic model building and refinement. Errat showed the comparative error value of the structured model. The overall quality of model of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase in ERRAT analysis was 81.961 while in case of N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase is 79.952. The respective values of torsion angle energy, C_β interaction energy, solvation energy, secondary structure, and solvent accessibility are –1.46, 0.38, 0.74, 1.83, and 0.08 in case of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase where –0.12, 0.75, –1.91, 0.50, –0.00 in case of N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase. The QMEAN for phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase and N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase is 0.751 and 0.714, respectively. Z score result is also shown in Table 3.

COACH generates protein-ligand binding site on the basis of two developed method (TM-SITE, based on binding-specific substructure comparison and S-SITE, based on sequence profile alignment) along with considering COFACTOR, FINDSITE, and CONCAVITY results.

CONCAVITY results showed that a total number of 27 residues (–196, 199, 281, 301, 303, 305, 306, 339, 342, 343, 344, 345, 347, 361, 365, 436, 438, 459, 461, 462, 466, 472, 509, 510, 531, 532, and 533) of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase are associated with creating ligand binding pocket. A similar pattern of concavity result was also found for N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase in which a total number of forty amino acid residues were involved in comprising the ligand binding pocket of the proteins (23, 24, 27, 50, 91, 94, 95, 115, 116, 118, 120, 123, 124, 125, 128, 164, 165, 166, 167, 170, 191, 193, 234, 235, 236, 240, 261, 300, 301, 302, 306, 307, 308, 330, 331, 373, 374, 400, 401, and 402).

Furthermore, S-SITE result represents the possible ligands that can bind with phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferas as well as N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase and ranked them according to confidence score (C-score), C-score ranges from 0 to 1 where a higher score implies a more reliable prediction. Among the predicted ligands for phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase, PPR or 3-phosphonopyruvate was exhibited as the top ranked ligand having a confidence score (C-score) of 0.45 and interacting with total eleven residues (301, 303, 339, 436, 438, 459, 460, 461, 462, 509, and 510) those are also resides within predicted ligand binding pocket of the protein. The best predicted ligand for N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyl-transferase was SKP or 5-(1-carboxy-1-phosphonooxy-ethoxyl)-shikimate-3-phosphate, representing C-score 0.41 and interacting with total number of sixteen residues (23, 24, 28, 94, 95, 98, 123, 165, 166, 167, 308, 330, 334, 373, 374, and 400) that are also common in the ligand binding pocket of the protein (Fig. 6).

Discussion

To nullify the 2,643 proteins from total 4,630 redundant proteins of F. nucleatum stain ATCC 25586 the CD-HIT program used at 60% identity [3536]. After BLASTP analysis, human non-homologous proteins were selected to avoid unwanted cross-reactions and cytotoxicity. BLASTP against DEG identified the essential genes. The genes that are vital to maintain cellular life are referred to as essential genes. Essential gene products of pathogen can become promising novel drug targets owing to the reason that most antibiotics attack cellular processes in bacteria [3237]. Essential genes which are exclusive to an organism can be regarded as species-specific therapeutic targets [33].

Sub-cellular localization of proteins has an important role in drug targets prediction arena. Proteins situated in cytoplasmic membrane are considered more valuable for target site.

3D structure of protein molecules exposes the molecular basis of protein function and thus allows an efficient design of experiments, for example, site-directed mutagenesis, disease-related mutation analysis, or the structure based design of specific inhibitors [38]. That is why, the determination of the 3D structure of a protein molecule is central to its understanding and manipulation of biochemical and cellular functions [39].

In case of each protein, greater than 90% confidence match was obtained except PTS system fructose-specific IIABC component protein. A high confidence match indicates that, overall fold of the models were almost accurate and the central core of the model was correct as well [34].

Ramachandran plot statistics of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase showed that most of the amino acid residues (above 90% of amino acid residues) were found in most favoured regions indicating that the protein models were of very good quality.

The program functions based on the analysis of statistics of non-bonded interactions between different atom types [40]. Verify 3D graph and a value of 0.85 of phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase in contrast to the value 0.72 for N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase indicates that environmental profile phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase is fairly good [4142]. The QMEAN assesses the global quality of the models based on a linear combination of six structural descriptions. The local geometry model is analyzed by calculating torsion angel potential over three consecutive amino acids. The long range interactions are assessed by estimating secondary structure specific distance dependent pairwise residue level potential. A solvation potential reveals the burial state of the residues. Simple sequence editor and auto cross covariance conformity indicates that the assessment between the predicted and calculated secondary structure and solvent accessibility is of good quality [434445].

Specifying exact ligand-binding site on protein is a crucial step in rational designing of novel therapeutic molecules to modulate the protein functions [46]. TM-SITE and S-SITE, along with considering COFACTOR, FINDSITE, and CONCAVITY results which increases Matthews correlation coefficient by 15% over the best individual predictions and these predictions are considered reliable and accurate in recent times [47].

Moreover, pharmaco-chemical properties of the PPR and SKP that were retrieved from the DrugBank Database indicate that these compounds are non-carcinogenic, non-toxic and moderately absorbable by human intestine (absorption probability, 0.7197 and 0.5233, respectively) [48]. Hence, the activity of the phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase can be inhibited by the PPR, derivatives of PPR or PPR related compounds. Likewise, the activity of the N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase probably can be hindered by SKP, derivatives of SKP or SKP related molecules. Since, phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase and N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase were identified as the essential proteins for the bacterial survival, blocking the function of these two enzymes can be a novel way to treat F. nucleatum–associated diseases. However, further research should be conducted both in vivo and in vitro to ascertain this result.

Understanding the docking studies with phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase, PTS system fructose-specific IIABC component, and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyl transferase protein as a receptor and protoporphyrin IX as a ligand. Analysis of the lowest docked energy value, the involvement of H-bonds, calculated root mean square deviation value, and interacting residues was considered [49].

The interactions between the amino acid residues in active sites and the ligand molecules derived in this study would be valuable to understand the potential mechanism of residues and the drug binding. It is evident that that protoporphyrin IX is involved in similar hydrogen bond interactions with proteins and thus the results found in our study are significant. However, to consider these proteins as valid target for drug designing, the future researchers also need to think about the possibility that these same functional proteins may exist in some other beneficial bacteria from human microbiota.

In conclusion, in this era of genomic science, subtractive genomic approach to drug designing has been greatly facilitated by the plethora of bacterial genomic information. The demand for new classes of antibacterial drug is increasingly growing as drug resistance challenges the effectiveness of existing therapies. Hence, there are obvious benefits for the identification and evaluation of new therapeutic targets and which is why this study has scrutinized the proteome of oral pathogen F. nucleatum adopting the subtractive genomic approach and identified two promising novel therapeutic targets along with predicting their 3D structures, ligand binding sites and corresponding ligands as well. These findings have now paved the way for design and development of novel inhibitors for F. nucleatum using the structure based drug design strategy.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to DilUmme Salma Chowdhury (University of Chittagong, Bangladesh) for her technical support and valuable suggestions to carry out this project.