Introduction

Neuropeptides, which signal between neurons, are known to be involved in a variety of physiological processes, including addiction, depression, hunger, pain, fear, anxiety, and circadian rhythms [1,2]. Neuropeptides are 3–100 amino acid residues long and up to 50 times larger than classic neurotransmitters [3]. The term "neuropeptides" was first introduced by De Wied [4] in 1971 to describe an endogenous peptide synthesized in nerve cells. While peptide hormones are also considered important intercellular signaling molecules, there are differences between neuropeptides and peptide hormones. That is, neuropeptides are secreted from neuronal cells (primarily neurons but also glia for some peptides) and signal to neighboring cells (primarily neurons), whereas peptide hormones are secreted from neuroendocrine cells and act on distant tissues by traveling through the blood [2,5]. Approximately 100 different neuropeptides are currently known to function in cell-to-cell signaling (http://www.neuropeptides.nl). Neuropeptides bind to post-synaptic receptors and elicit cellular responses like classical neurotransmitters.

Neuropeptide Synthesis

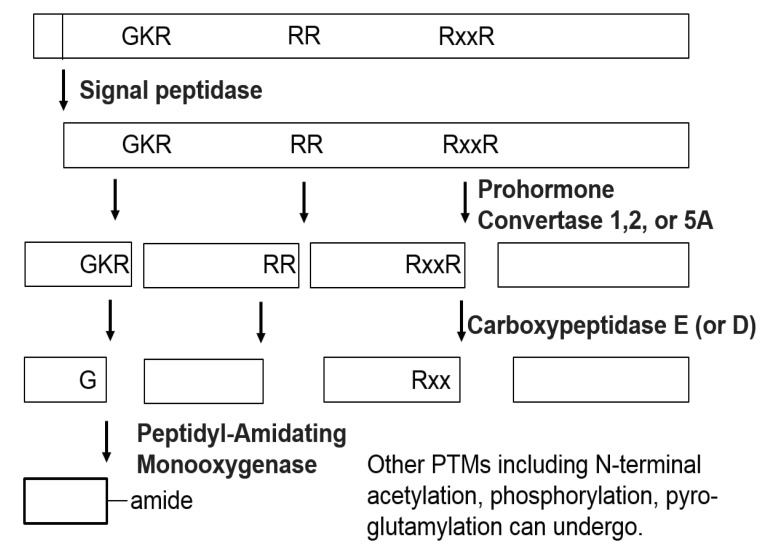

Neuropeptides are produced from precursor proteins (or prohormones) by a series of enzymatic processing steps. The neuropeptide precursors generally do not have functions on their own, requiring processing to generate the active forms. The precursors are synthesized on ribosomes at the endoplasmic reticulum and processed through the Golgi [5]. When the NH2-terminal signal peptide of the neuropeptide precursors is cleaved by signal peptidase, the precursors are routed to the Golgi apparatus and packaged into dense-core secretory vesicles together with processing proteases, termed convertases. Most neuropeptide precursors are first processed by endopeptidases, including prohormone convertase 1 (also known as prohormone convertase 3) and prohormone convertase 2 and, to a lesser extent, prohormone/proprotein convertase 5A (also known as prohormone/proprotein convertase 6A) [6]. The endopeptidases typically cleave at pairs of basic amino acids, usually Lys-Arg (KR) or Arg-Arg (RR) sites, but on occasion, the basic amino acids are separated by 2, 4, or 6 other amino acids (Fig. 1). The next stage of processing is the removal of C-terminal basic residues in the mature secretory vesicle. Carboxypeptidase E is the exopeptidase primarily responsible for removing the C-terminal basic residues, and carboxypeptidase D has also been shown to act in this role. After removal of the C-terminal basic residues, other enzymes perform additional post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as amidation, acetylation, phosphorylation, sulfation, and glycosylation [6]. For example, peptides with a C-terminal glycine are typically converted to the amide by peptidyl-α-amidating monooxygnenase [7], and tyrosine sulfation is known to be mediated by tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase [8]. These final bioactive forms of the peptides are stored within secretory vesicles that are accumulated within the cells. When the cells are stimulated, the secretory vesicles are known to fuse with the cellular membrane to release the neuropeptides into the extracellular environment [2]. The secreted neuropeptides can interact with receptors containing specific binding sites. The receptors are often G-protein-coupled receptors. The interaction of the neuropeptides with the receptors causes a conformational change in the receptor, resulting in the production of a cellular response through a variety of mechanisms, depending on the type of receptor.

While a single neuropeptide precursor often produces multiple neuropeptides, the proteolytic processing of the precursor protein occurs in a tissue-specific and even region-specific manner. A classic example is the processing of the precursor proopiomelanocortin in the pituitary. In the anterior lobe of the pituitary, the precursor is converted into adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which binds to several subtypes of melanocortin receptors, such as MC2R, located in the adrenal gland; this receptor controls the production of glucocorticoids (cortisol) [9,10]. In the intermediate lobe of the pituitary and also in the brain, ACTH is further processed into alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, which binds to melanocortin receptors with completely different affinities [11]. The PTMs can also regulate the bioactivity and stability of the neuropeptides and therefore affect the binding affinities of the neuropeptides for the receptors. For example, acetylation of the N-terminus of β-endorphin removes the ability of the peptide to stimulate opioid receptors and to produce analgesia [6]. Conversely, octanoylation of the peptide ghrelin on a serine residue is essential for the binding of the peptide to its receptor [12]. Although the various aspects of peptide synthesis, including PTMs, lead to an increase in neuropeptide complexity, unveiling new peptides and unreported peptide properties is critical to advancing our understanding of nervous system function.

Clinical Importance of Neuropeptides

While neuropeptides are involved in a wide range of physiological processes, including hunger, food intake, body weight regulation, and circadian rhythms, it has been shown that dysregulation of neuropeptides often results in a variety of neurological disorders [13,14,15]. Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures. Neuropeptides, such as arginine-vasopressin, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), enkephalin, β-endorphin, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), and tachykinins, were shown to have proconvulsive effects, whereas other neuropeptides, like ACTH, angiotensin, cholecystokinin, somatostatin, and thyrotropin-releasing hormone, were able to suppress seizures in the brain [16]. In addition, neuropeptides, such as dynorphin and substance P, were shown to be involved in the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease, which is a neurodegenerative disease with motor and non-motor symptoms [17]. Progression to addiction is also known to be influenced by several peptidergic neuromodulators. A few orexigenic neuropeptides, including galanin, enkephalin, and orexin/hypocretin, were shown to have a positive feedback relationship to alcohol, while other hypothalamic neuropeptides, such as dynorphin, CRF, and melanocortins, showed a negative feedback relationship to alcohol intake. Dysregulation of these multiple neuropeptides is assumed to result in alcohol addiction [18]. There was also a report that neuropeptides, such as substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptides, vasoactive intestinal peptide/PACAP, and neuropeptide Y (NPY), are associated with regulation of cutaneous immune responses and tissue maintenance and repair. Due to these diverse functions of neuropeptides, neuropeptides and neuropeptide receptors have been drug targets for the treatment of neurological disorders [3,19].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Neuropeptidomics

Traditional methods of neuropeptide analysis

Traditionally, the analysis of neuropeptides was performed by Edman sequencing, in which the N-terminal amino acid is sequentially removed. The method was developed by Edman in 1950 and is used for neuropeptide sequencing in many different species—for example, NPY in the porcine brain [20] and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the dogfish brain [21]. However, analysis by this method is slow and does not allow for the sequencing of neuropeptides containing N-terminal PTMs [22]. Immunological techniques, such as radioimmunoassay (RIA) and immunohistochemistry (IHC), have been used for measuring relative neuropeptide levels and spatial localization. RIA has been a popular tool to quantify neuropeptides in biological samples, such as NPY [23] and galanin in the rat brain [24]. Although RIA is a relatively sensitive technique capable of absolute quantification of peptide levels, it is not always specific for a single-peptide form because of its antibody-based detection method. In addition, unless specific antibodies are available for the different isoforms, RIAs do not distinguish between these modifications. IHC has provided essential information regarding the localization of neuropeptides within the complexity of the brain structure, improving our understanding of the distribution of peptides. However, IHC does not report the actual size or full identity of the peptide, including PTMs. In addition, these antibody-based methods require a priori knowledge of a potential neuropeptide in order to generate antibodies specific to the neuropeptides and only detect peptide sequences with known structures.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Peptidomics

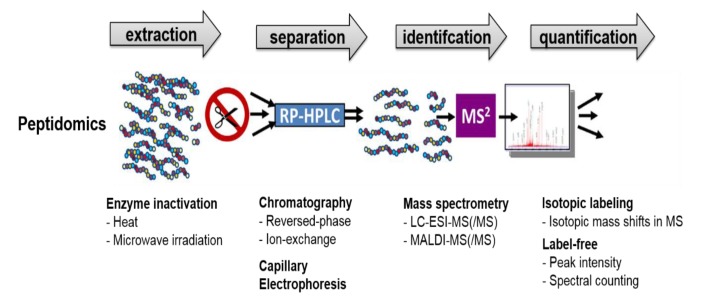

In contrast to immuno-based methods, mass spectrometry (MS) enables one to detect and identify the precise forms of neuropeptides without a priori knowledge of the peptide's identity, resulting in the identification of previously unknown neuropeptides. MS has been used to identify and characterize hundreds of endogenous peptides in various animals [25,26,27,28,29]. The high-throughput discovery of neuropeptides based on MS has made up the field of peptidomics (Fig. 2) [6,30,31,32,33]. While typical proteomic analysis involves the digestion of proteins using proteases, such as trypsin, to generate peptides that can be readily sequenced by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), peptidomics focuses on the analysis of the native peptide forms, including PTMs, without using digestive enzymes. Therefore, it is important to identify and characterize as many neuropeptides as possible, because each peptide can have its own biological function. While MS-based peptidomics can be utilized to characterize a large number of neuropeptides simultaneously, it can be also applied to the quantification of individual neuropeptides.

Sample Preparation for Peptidomics Experiment

Although MS allows the identification of a large number of neuropeptides in a high-throughput manner, sample preparation prior to MS is a critical step that affects peptide identification coverage in peptidomics experiments. When the animal is sacrificed and the brain tissue of interest is obtained, proteases rapidly degrade larger proteins into smaller peptides that fall into the mass range of neuropeptides. The presence of degraded products derived from highly abundant proteins often complicates the MS analysis and interferes with the identification of less abundant neuropeptides. Different techniques, including focused microwave irradiation before decapitation, microwave irradiation after decapitation, and boiling the tissue immediately after decapitation, have been used in order to inactivate the proteases responsible for the high background of protein degradation fragments [32,34,35,36,37,38]. In addition to the procedures of protease deactivation, peptide extraction and subsequent treatment are other steps that affect the number of identified neuropeptides. The use of different solvents and procedures can affect the peptide profiles detectable in brain tissue. Che et al. [31] compared different extraction conditions for the recovery of neuropeptides from mouse hypothalamus. They found that sonication and heating in water (70℃ for 20 min), followed by cold acid and centrifugation, enabled the efficient extraction of many neuropeptides without the formation of the protein degradation fragments seen with hot acid extractions. Bora et al. [39] and Lee et al. [37] also showed that multiple stages of peptide extraction, including boiling water, acidified acetone, and acetic acid, were able to maximize the number of identified neuropeptides from their respective analyses of supraoptic nucleus and suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) samples in the rat brain.

MS Analysis

After sample processing, the extracted peptides are subjected to MS analysis. A mass spectrometer consists of an ionization source, a mass analyzer separating the ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), and a detector recording the number of ions at each m/z value. Two commonly used types of ionization are electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI). While each approach has its own advantages, MALDI is more tolerant to the presence of salts. Thus, MALDI is often applied to direct tissue profiling or molecular ion imaging from tissue sections. Direct tissue sample analysis by MALDI-based MS is usually performed by a simple sequence of steps, which include placing the tissue of interest on the MALDI plate, applying a droplet of matrix, and irradiating the co-crystallized tissue to cause desorption/ionization of the peptides [30]. MALDI imaging provides valuable information pertaining to the spatial localization of neuropeptides [40]. Although MALDI-MS can be interfaced with separation strategies, such as liquid chromatography (LC) and capillary electrophoresis, ESI-MS can be coupled more easily with the separation methods, because the ions are produced as an aerosol from the liquid phase with a high voltage in ESI. The introduction of a nano-electrospray, based on capillary LC, coupled to MS, significantly increases the sensitivity in LC-ESI-MS, and furthermore, the preferred formation of multiple-charge states in ESI allows for more comprehensive MS/MS fragmentation data.

MS Data Analysis for Neuropeptide Identification

While neuropeptides can be identified by comparing experimental peptide masses obtained from MS data against a list of known neuropeptide masses, they are typically identified with both MS and MS/MS fragmentation data. While collision-induced dissociation is widely used for peptide identification, other fragmentation methods, such as higher energy collision dissociation and electron transfer dissociation, have recently improved the identification capability of peptides and PTM localization [41,42,43]. The automated identification of neuropeptides based on their MS and MS/MS data is pursued by using proteomic-based search engines, such as Mascot, SEQUEST, X!Tandem, Peaks Studio, and ProSightPC [37,44,45,46,47]. Since peptidomics searches typically employ criteria, such as no enzymatic cleavage and various common modifications (e.g., N-terminal acetylation and C-terminal amidation), they often require a larger search space and longer search times for peptide identification. Several neuropeptide prohormone databases, including SwePep, have been constructed to facilitate neuropeptide identification, and cleavage prediction programs, such as NeuroPred, were developed to predict cleavage sites in prohormones and to provide the masses of the resulting peptides [48,49]. In addition to the database search strategies, neuropeptides can be also identified by de novo sequencing, especially when the species of interest does not have a sequenced genome. While peptide spectra are compared with theoretical peptides in the database search strategy, de novo sequencing, which is the direct assignment of the amino acid sequence from the MS/MS spectrum, can be pursued when the database is not available. Although de novo sequencing can be performed manually, the process is labor-intensive and time-consuming. There are several software packages that can perform de novo sequencing directly on MS/MS data, including Lutefisk (http://www.hairyfatguy.com/lutefisk/), Mascot Distiller (Matrix Science), and PEAKS (Bioinformatics Solutions, http://www.bioinformaticssolutions.com/) [30]. The peptide sequences obtained from de novo sequencing are often compared with the nonredundant database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information to establish the peptide identities with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). The BLAST search compares a partial neuropeptide sequence against the database of a closely related species.

Quantitative Neuropeptidomics

MS-based peptidomic techniques allow for measuring relative levels of peptides in different conditions of the samples, as well as peptide identification. Quantitation of peptides based on MS is generally achieved either by stable isotope labeling or label-free approaches (Fig. 3) [50,51]. In stable isotope labeling, the relative levels of peptides in two different samples are typically examined by labeling the peptides in one sample with a light stable isotope and those in the other sample with a heavy stable isotope; the two samples are then combined and analyzed together. The relative levels of the peptides are calculated by the difference in the MS peaks (peak intensity or peak area) of the two samples. While the stable isotopes can be introduced to the peptides either metabolically or through chemical reactions, isotope labeling through chemical reactions enables one to obtain quantitative information from biological samples, such as brain tissues, for which metabolic labeling is not available. A number of different isotopic tags, including acetic anhydride, succinic anhydride, and trimethylammonium butyrate (TMAB), have been used for quantitative analyses of endogenous peptides in various samples and conditions [6,34,52]. For example, the TMAB tag was used to evaluate the relative changes of endogenous peptides in response to food intake or drug treatment [53,54,55] and to assess the role of protein convertase 1/3 and 2 in the processing of the peptides in mouse models [56,57]. In label-free methods, each sample is prepared separately and then subjected directly to individual LC-MS or LC-MS/MS runs, followed by comparisons of either the mass spectral peak intensities of the detected peptides or the total number of MS/MS spectra identified for a peptide, called spectral counting [51]. Since there is no limit to the number of samples that can be compared, label-free quantitation allows for the comparison of multiple samples or conditions. The approach has been used to measure the changes in the levels of neuropeptides present during the daytime and nighttime in the rat SCN [58,59] and to examine the expression changes of endogenous peptides involved in the embryogenesis of Japanese quail brains [60] and the nucleus accumbens of morphine-dependent rats [61]. In addition, quantitative peptidomic analyses based on peak intensities has enabled us to discover endogenous peptides associated with repeated exposure to amphetamine and with individual variations in sensitivity to the behavioral effects of cocaine in rat models [62,63].

Conclusion

Neuropeptides are important signaling molecules that are involved in many kinds of physiological processes, including addiction, depression, mood regulation, and circadian rhythms. Because of their biological significance, neuropeptides have become key targets in drug discovery. While immunological techniques, such as RIA and IHC, require a priori knowledge of neuropeptides and only detect peptide sequences with known structures, MS enables one to detect and identify the precise forms of neuropeptides without a priori knowledge of peptide identity, resulting in the identification of previously unknown neuropeptides. In addition, MS-based quantitative analyses of neuropeptides based on either stable isotope labeling or label-free methods provide information on the relative levels of neuropeptides in different physiological conditions, which can be helpful in understanding the function of the neuropeptides. Continuous efforts to implement current MS-based peptidomics techniques for neuropeptide identification and quantitation are expected to provide more profound insights into the neurochemical communication of neurons in various physiological processes.