In Silico Docking to Explicate Interface between Plant-Originated Inhibitors and E6 Oncogenic Protein of Highly Threatening Human Papillomavirus 18

Article information

Abstract

The leading cause of cancer mortality globally amongst the women is due to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. There is need to explore anti-cancerous drugs against this life-threatening infection. Traditionally, different natural compounds such as withaferin A, artemisinin, ursolic acid, ferulic acid, (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, berberin, resveratrol, jaceosidin, curcumin, gingerol, indol-3-carbinol, and silymarin have been used as hopeful source of cancer treatment. These natural inhibitors have been shown to block HPV infection by different researchers. In the present study, we explored these natural compounds against E6 oncoprotein of high risk HPV18, which is known to inactivate tumor suppressor p53 protein. E6, a high throughput protein model of HPV18, was predicted to anticipate the interaction mechanism of E6 oncoprotein with these natural inhibitors using structure-based drug designing approach. Docking analysis showed the interaction of these natural inhibitors with p53 binding site of E6 protein residues 108-117 (CQKPLNPAEK) and help reinstatement of normal p53 functioning. Further, docking analysis besides helping in silico validations of natural compounds also helped elucidating the molecular mechanism of inhibition of HPV oncoproteins.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) accounts for 5.2% of all cancers globally. Besides cervical cancer HPV also causes a subset of anogenital, head and neck cancers [12]. Most of the cancer mortality in women worldwide is due to cervical cancer with an estimated 527,624 new cases and 265,653 annual mortality [3]. Among more than 200 HPV types, mostly HPV type 18 and 16 are the main cause of cervical cancer i.e., 15.7% and 62.6%, respectively [4]. Further, HPV 16 and 18 are also associated with penile cancer (63%-80%), vulva/vaginal cancers (80%-86%), anal cancer (93%), oropharyngeal cancers (89%-95%), etc. [5]. Thus, these two HPV types are the main targets for designing anti cancer drugs. The HPV onco-proteins E6 and E7, have been reported to interact with tumor suppressor proteins p53 and pRb respectively [6]. Both p53 and pRb act as negative regulator of cell cycle and inhibit G0-G1 and G1-S phase transitions.

These interactions apparently play important roles in the induction of cell immortality. The importance of p53-mediated apoptosis has been recognized in terms of maintaining homeostasis and preventing neoplastic transformation. E6 forms a ternary complex with p53 and E6 associated protein (E6AP) resulting in the degradation of p53 via ubiquitination pathway [7].

Although HPV has been known to be a causative agent for cervical cancer for more than three decades, the effective treatment against HPV infection is yet to be established [8]. Many natural plant origin compounds have been identified as promising sources of drugs for treatment and prevention of cancer in the recent years [910].

Indole-3-carbinol, an active ingredient of cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, etc. was reported with anti-estrogenic properties in cervical cells [11]. Ursolic acid having anti-mutagenic nature has the potential to induce apoptosis in tumor cells as well as to prevent malignant transformation of normal cells [12]. Resveratrol is a polyphenol isolated from the grapes skin, shown to alter both cell cycle progression and the cytotoxic response to ionizing radiation in cervical tumor cell lines [13]. Curcumin is cytotoxic to cervical cancer cells in a concentration dependent and time-dependent manner and the cytotoxicity was higher in HPV infected cells. It down regulates both serine kinase AKT/nuclear factor κB pathway by sensitizing cancer cells [14]. It also down regulates the expression of HPV oncoproteins, resulting in loss of the transforming phenotype and the cessation of cellular growth. Singh and Singh [15] explored other molecular mechanisms exerted by curcumin in cervical cancer cells, showing that it inhibits telomerase activity, RAS and ERK signaling pathway, cyclin D1, cyclooxygenase 2, and inducible nitric oxide synthase activity [15]. Ginger (active ingredient, gingerol) is a natural dietary component, which has antioxidant and anticarcinogenic properties and its supplementation has shown to suppress colon carcinogenesis [16]. Jaceosidin, a active ingredient of Artemisia argyi, reported to inhibit the binding between oncoproteins and tumor suppressors p53 [17]. Through the post-attachment heparan sulfate-independent effect, it is reported that carrageenan block HPV infection by preventing the binding of HPV virions to cells [18]. Due to the antiviral and antitumor properties of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), it was found effective in HPV patients with infected cervical lesions [19]. EGCG also reported as an effective inhibitor of E6/E7 proteins due to its inhibitory effect on the growth of HeLa (HPV18 positive) and CaSki (HPV16 positive) cells in a time and concentration dependent manner [20]. Mahata et al. [21] studied the effect of berberine on HPV16 and HPV18 positive cervical cancer cell line, and observed that it can effectively target both the host and viral factors responsible for development of cervical cancer through inhibition of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 expression. An in vitro study conducted by Karthikeyan et al. [22] reported the radiosensitizing potential of ferulic acid (a natural phenolic acid) on human cervical cancer cell lines (HeLa and ME-180) [22]. Silymarin, an active ingredient contained in the seeds of the milk thistle plant, reported to inhibit cervical cancer cell [23]. Hu et al. [24] evaluated the anti-tumor effect of dihydroartemisinin (DHA), an artemisinin derivative on HeLa and Caski cervical cancer cells and found that DHA treatment caused a considerable inhibition of tumor development [24]. The active compound of Withania somnifera i.e., withaferin A (WA) has reported to have antitumor, antiangiogenic and radiosensitizing activity [2526]. Through in vitro and in vivo study Munagala et al. [27] demonstrated the effective inhibition of proliferation of cervical cancer cells by WA. Further, they showed the down regulation of HPV E6 and restoration of p53 pathway by WA [27].

In the present study, we explicate the atomic interaction between plant-originated ligands and high risk HPV18 E6 oncogenic protein. This study comprises of protein structure modeling of HPV18 E6 protein employing Phyre2 server followed by structural refinement and energy minimization by Yet Another Scientific Artificial Reality Application (YASARA) energy minimization server. To analyze the molecular interaction between HPV18 E6 onco-protein with natural ligands, AutoDock4.2 tool was used in this study.

Methods

Hardware and software

Dell Workstation with Windows operating system having 500 GB hard drive, 6 GB RAM and 2.26 GHz processor was employed in this study. Different online resources and AutoDock 4.2 were used in this study.

HPV18 E6 protein

As HPV18 E6 protein was selected as drug target in this study, its amino acid sequence (GenBank ID: NP_040310.1) was retrieved from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Prediction of protein structure and its validation

Phyre2 server [28] was employed for modeling of the tertiary structure of E6 protein followed by energy minimization using YASARA Energy Minimization Server [29]. Further the protein three dimension structure in pdb format was subjected to SCWRL4.0 software [30] for protein side chain modeling before docking. Procheck [31], ProSA-web [32], and ProQ [33] server were used for assessing the model reliability which further verified by ERRAT server [34].

Ligand preparation and protein-ligand docking

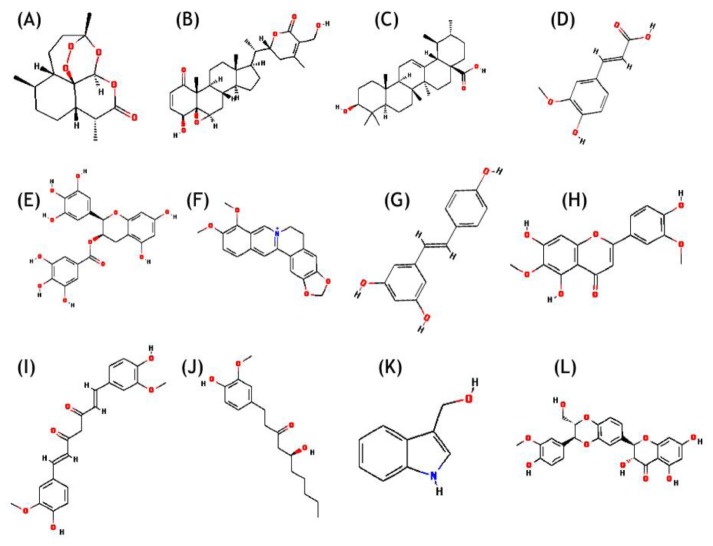

Chemical structures along with Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry number of 12 natural compounds reported in literature (Fig. 1) (artemisinin, WA, ursolic acid, ferulic acid, EGCG, berberin, resveratrol, jaceosidin, curcumin, gingerol, indol-3-carbinol, and silymarin), were retrieved from PubChem database (Table 1) [35]. Receptor molecules (HPV18 E6) was prepared in AutoDock 4.2 program [36] and docking studies were performed as per the standard methodology for protein-ligand docking used by Kumar et al. [37].

Chemical structure of natural compounds. (A) Artemisinin. (B) Withaferin A. (C) Ursolic acid. (D) Ferulic acid. (E) (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate. (F) Berberin. (G) Resveratrol. (H) Jaceosidin. (I) Curcumin. (J) Gingerol. (K) Indol-3-carbinol. (L) Silymarin.

Visualization

ADT tool and PyMol molecular graphics system (http://www.pymol.org) were used for visualizing the structure files.

Results and Discussion

Protein structure prediction and validation

There are 158 amino acids in the protein sequence of HPV18 E6 protein. As the experimentally determined tertiary structure of E6 was not available, Phyre2 server was used to predict its three dimensional structure. During structure prediction, crystal structure of C chain of full-length HPV oncoprotein e62 in complex with lxxll peptide of ubiquitin ligase E6AP (PDB ID, 4GIZ) was taken as structural template by Phyre2 server. There was query coverage of 89% and identities of 57% observed between target-template alignment. Upon structural refinement of predicted structure by YASARA Energy Minimization Server, the total energy of refined structure was observed to be -19,732.64 kcal/mol (score, 0.07), whereas it was as 166,485.03 kcal/mol (score, -0.55) prior to energy minimization.

Upon Procheck analysis, 99.2% residues of the refined model (Fig. 2A) were found in most favourable region and additional allowed regions and only 0.8% (Ser59) residue in situated generously allowed region, whereas not a single residue observed in the disallowed region of Ramachandran plot (Fig. 2B). The compatible Z score (Fig. 2C) value was observed to be -4.46 by ProSA-web evaluation, which is quite well within the native conformations range of crystal structures [31]. The residue energy of the refined model were observed to be largely negative (Fig. 2D). The Protein Quality Predictor (ProQ) tool predict the LG score of 2.205 for HPV18 E6 protein model, implying high precision of the modeled structure as ProQ LG score of more than 1.5 is essential for signifying that a predicted structure is of fairly good quality [33]. The overall quality factor is predicted to be 91% by the ERRAT plot (Fig. 2E) showing the well accuracy of predicted structure. Overall, based on the above results, the reliability of the predicted model was suggested.

(A) 3D structure of predicted human papillomavirus (HPV) 18 E6 model. (B) Ramachandran plot of predicted E6 model (The red, dark yellow, and light yellow regions represent the most favored, allowed, and generously allowed regions). (C) ProSA-web Z-scores of all protein chains in Protein Data Bank (PDB) determined by X-ray crystallography (light blue) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with respect to their length. The Z-score of E6 was present in that range represented in black dot. (D) Energy plot for the predicted E6 of HPV18. (E) ERRAT plot for residue-wise analysis of homology model.

Interaction study of HPV18 E6 with natural ligands through docking analysis

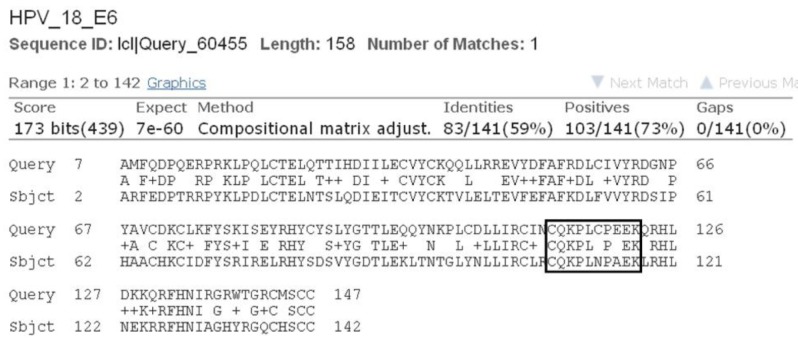

As all the natural compounds were observed to be interact with E6 protein in different conformations and binding energy, the conformation with lowest binding energy was selected for analysis (Table 2). In case of HPV16 E6 protein, amino acid residues 113-122 (CQKPLCPEEK) were associated with p53 binding [38]. In our previous study we elucidated molecular interaction of HPV16 E6 proteins with natural inhibitors around these p53 binding site [37]. Upon BLAST [39] sequence comparison of E6 protein of HPV16 and HPV18, it was observed that 80% of the p53 binding residues, conserved in E6 of HPV18 (Fig. 3). Thus, on the basis of molecular interaction of p53 binding site residues with E6 protein, the active site residues i.e., 108-117 (CQKPLNPAEK) of HPV18 E6 protein were consider for docking analysis.

Sequence alignment results of E6 protein of human papillomavirus (HPV) 18 and HPV16 showing conserved p53 binding site residues.

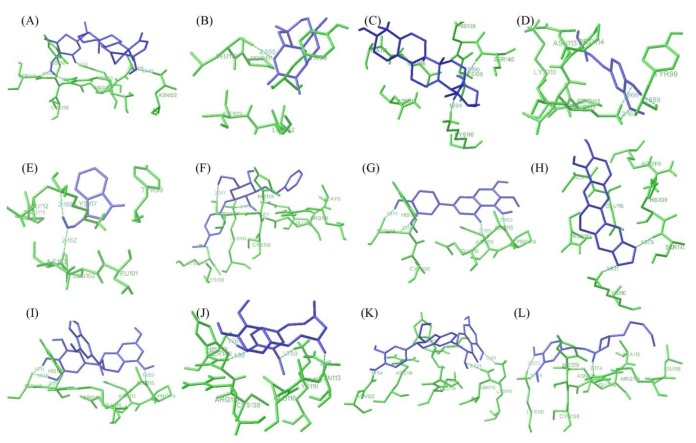

Fig. 4 showed best docking conformation of E6 protein with twelve ligand molecules and the complete interactions were put in Table 2. It was observed that all the ligands were interacting with E6 protein at p53 binding site residues. WA was observed to bind with HPV18 E6 protein with lowest binding energy of -5.85 kcal/mol and the inhibition constant was found to be 51.35 µM. It was found to interact with four amino acid residues of E6 (Glu116, Asn113, Asn122, and Ser140) by forming hydrogen bonds. Next to WA, artemisinin bound with E6 protein with binding energy of -5.68 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 68.22 µM. It formed only one hydrogen bonds with the receptor at Leu112 residues. Ursolic acid and ferulic acid also observed to inhibit E6 protein with good binding affinity i.e., binding energy of -5.31 and -5.18 kcal/mol, respectively. Other six natural compounds indol-3-carbinol, resveratrol, jaceosidin, berberine, EGCG, and curcumin were observed to bind with the receptor (E6 protein) with binding energy range from -4.98 kcal/mol to -4.08 kcal/mol (Table 2). Further, other two compounds silymarin and gingerol found to interact with the receptor with less binding affinity i.e., binding energy of -3.67 kcal/mol and -2.86 kcal/mol.

Interaction profile of E6 with natural ligands. (A) Withaferin A. (B) Artemisinin. (C) Ursolic acid. (D) Ferulic acid. (E) Indol-3-carbinol. (F) Resveratrol. (G) Jaceosidin. (H) Berberin. (I) (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate. (J) Curcumin. (K) Silymarin. (L) Gingerol showing interaction of ligands with the active site residues of E6 by forming hydrogen bonds.

Few recent in silico studies are also been carried out on HPV showing the importance of computational approach in drug designing. Muthukala et al. [40] observed the inhibitory effect of quercetin compound against human cervical cancer cell line proteins through in silico docking analysis. Kotadiya and Georrge [41] identified some putative drugs from natural products against HPV through in silico approach. Samant et al. [42] studied the molecular interactions of human immunodeficiency virus antiviral drugs against HPV18 E6 through in silico approach. Mamgain et al. [43] also observed the inhibitory effect of natural compounds such as colchine, curcumin, daphnoretin, ellipticine, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, etc. against HPV16 E6 protein using molecular docking [43]. In our study, we have taken 12 natural compounds, reported to be used as an anti cancer agent against HPV [1112131415161718192021222324252627] for docking analysis and observed their molecular interaction against HPV18 E6. All the natural compounds were found to interact with p53 binding site residues of HPV18 E6 onco-protein.

This interaction might disable E6 protein to bind with the host p53 protein helping correlate these natural compounds used as anti-cancerous agents to treat HPV infections.

For treatment of different cancers caused by HPV, various plant-originated compounds have been identified and tried as hopeful resources for cancer therapy. Due to the encroachment in computational biology and bioinformatics, validation of those natural compounds is possible through computational approach. The E6 protein of HPV6 and HPV11 (low risk HPVs) is not able to degrade p53 protein whereas in case of high risk HPVs (HPV16 and HPV18), the E6 protein able to inactivate p53 protein by inducing its degradation. Thus, in order to design a novel drug against cervical cancer, the HPV18 E6 protein can be considered as a suitable target. In this study, high throughput computational approach have been employed for modeling tertiary structure of E6 protein followed by docking using AutoDock 4.2. This computational approach needs to be explored further in order to design novel drugs against cervical cancer from natural resources.

Acknowledgments

Authors express gratitude to the Department of Biotechnology, MoS&T, Government of India for their financial support to Bioinformatics Centre wherein this study has been carried out. Grateful thanks to Shri D.S. Mehta, President, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. B.S. Garg, Secretary, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. K.R. Patond, Dean, MGIMS; Dr. S.P. Kalantri, Medical Superintendent, Kasturba Hospital, MGIMS, Sevagram & Dr. B.C. Harinath, Director, JBTDRC & Coordinator, Bioinformatics Centre for their encouragement & support.