Role of Chromosome Changes in Crocodylus Evolution and Diversity

Article information

Abstract

The karyotypes of most species of crocodilians were studied using conventional and molecular cytogenetics. These provided an important contribution of chromosomal rearrangements for the evolutionary processes of Crocodylia and Sauropsida (birds and reptiles). The karyotypic features of crocodilians contain small diploid chromosome numbers (30~42), with little interspecific variation of the chromosome arm number (fundamental number) among crocodiles (56~60). This suggested that centric fusion and/or fission events occurred in the lineage, leading to crocodilian evolution and diversity. The chromosome numbers of Alligator, Caiman, Melanosuchus, Paleosuchus, Gavialis, Tomistoma, Mecistops, and Osteolaemus were stable within each genus, whereas those of Crocodylus (crocodylians) varied within the taxa. This agreed with molecular phylogeny that suggested a highly recent radiation of Crocodylus species. Karyotype analysis also suggests the direction of molecular phylogenetic placement among Crocodylus species and their migration from the Indo-Pacific to Africa and The New World. Crocodylus species originated from an ancestor in the Indo-Pacific around 9~16 million years ago (MYA) in the mid-Miocene, with a rapid radiation and dispersion into Africa 8~12 MYA. This was followed by a trans-Atlantic dispersion to the New World between 4~8 MYA in the Pliocene. The chromosomes provided a better understanding of crocodilian evolution and diversity, which will be useful for further study of the genome evolution in Crocodylia.

Introduction

Crocodilians (Crocodylia) are extant large-sized reptiles found throughout the tropics in freshwater lakes, rivers, and oceans. Crocodilians diverged from birds, their closest living relatives as Archosauromorpha more than 240 million years ago (MYA). Ancestral crocodilian species first appeared in the fossil record around 80 MYA during the Late Cretaceous [1]. Extant crocodilians contain 25 species, classified into two families: Alligatoridae (comprising genera: Alligator, Caiman, Paleosuchus, and Melanosuchus) and Crocodylidae (comprising genera: Gavialis, Tomistoma, Mecistops, Osteolaemus, and Crocodylus) [2]. These crocodilians share both ancient and recent morphology as well as ecological characters [1]. The understanding of the phylogenetic history and biogeography in this lineage has provided a fascinating study for evolutionary biologists.

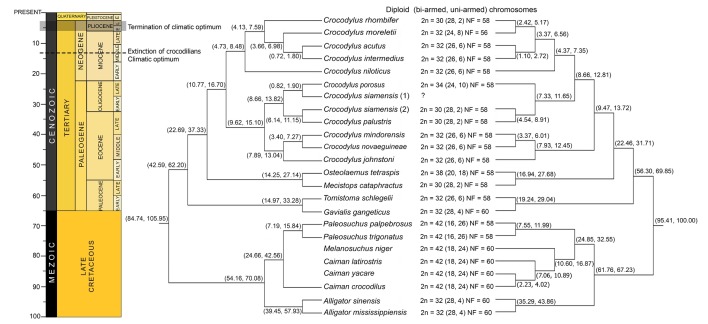

A phylogenetic approach for crocodilians was originally conducted based on fossil records. These suggested that the Indian gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) was a basal crocodilian [1]; however, molecular datasets indicated that Alligator diverged from the remaining crocodilians around 50~70 MYA in the Tertiary, of which Crocodylus are the most recent group (Fig. 1) [3456789101112131415161718192021222324]. This suggested that Alligator was the most ancient crocodilian; however, relationships among living species of Crocodylus remain poorly resolved, since they radiated into various species around 9~13 MYA during the middle of the Miocene [16]. These issues have received high priority in modern systematics by combining many datasets to determine the true groupings and divergences among them. One possibility is the level of different chromosome constitution, though crocodilians exhibit slow divergence of karyotype among living species. However, various karyotypic forms in the lineage are probably the source of reproductive isolation, which eventually radiated into species diversity.

Conflict between most molecular studies based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences (concatenated twelve protein coding sequences: ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4, ND4L, ND5, COI, COII, COIII, Cytb, ATPase 6, and ATPase 8) (left) and the mixture of several molecular loci (nuclear and mitochondrial DNA) (right) with regard to crocodilian phylogeny, divergence time, and karyological data. The majority-rule tree with interval node ages from the *BEAST posterior sample is conducted based on a conservative upper bound of 100 million year ago (MYA), placed on the root of Crocodylia (83.5~96.5 MYA) and on the divergence of Alligator-Caiman (64~71 MYA) [1, 18] (left image). The phylogenetic tree within Crocodylia was obtained from Oaks [16] with slight modification (right image). Karyological data were obtained from Cohen and Gans [19], Olmo and Signorio [20], Kawagoshi et al. [21], Srikulnath et al. [22], and Kasai et al. [23]. Estimated divergence times at individual nodes are shown with their interval ages. Crocodylus siamensis (1), complete mitochondrial genome of C. siamensis (DQ353946) sequenced by Ji et al. [24]; Crocodylus siamensis (2), complete mitochondrial genome of C. siamensis (EF581859) sequenced by Srikulnath et al. [17]. ?, no data on chromosome constitution; NF, fundamental number. In Crocodylus lineage, Indo-Pacific species is Crocodylus mindorensis, Crocodylus novaeguineae, Crocodylus johnstoni, Crocodylus siamensis, Crocodylus palustris, and Crocodylus porosus; New World species is Crocodylus moreletii, Crocodylus acutus, Crocodylus intermedius, and Crocodylus rhombifer; and African species is Crocodylus niloticus.

Remarkably, chromosomal investigation of 23 crocodilians revealed karyotypic features: small diploid chromosome numbers (30~42), the predominance of a few large chromosomes, and the absence of dot-shaped microchromosomes whose centromere positions are undetectable [1920]. This contradicts with the karyotypes of birds (the sister group of Archosauromorpha), and the relative lineage of turtles, which contain a small number of macrochromosomes and many indistinguishable microchromosomes [2025]. The increase of large bi-armed chromosomes and the presence of small chromosomes probably correlate with the reduction of medium acrocentric chromosomes and the absence of microchromosomes, respectively, in these lineages [2526]. The chromosome arm number or fundamental number (NF, bi-armed chromosome: metacentric or submetacentric = 2; uni-armed chromosome: acrocentric or subtelocentric = 1) of all crocodilian karyotypes shows little interspecific variation (56~60), and no sex chromosome heteromorphism has been recognized in any species [192027]. These characteristics of crocodilian karyotypes indicated that very few chromosomal rearrangements have occurred in Crocodylia, except for centric fusion and/or fission events. To delineate the role of chromosomal rearrangement, which also plays an evolutionary force in crocodilian diversity and evolution, the karyotype data and phylogeny were summarized as (1) variation of chromosome constitution within crocodilians compared to other sauropsids (birds and reptiles), (2) current phylogenetic history of crocodilians from molecular data and paleontological perspective, and (3) correlation of chromosomal rearrangements in each lineage and phylogeny in crocodilians.

Comparative Genomics for Crocodilians and Other Sauropsids

Sauropsids (birds and reptiles) number around 20,000 species, comprising large group diversity in birds (9,900 species) and squamate reptiles (9,700 species), but small diversity in turtles (340 species) and crocodilians (25 species) [2]. It is possible that the species richness of birds and squamate reptiles correlates with the large karyotype variability. By contrast, turtles and crocodiles show low chromosome constitution variability, although the correlation between chromosome changing rate and species number is found in turtles, but not in crocodiles [20282930]. This probably results from the role of sex chromosomes as all crocodilians exhibit temperature sex determination, but both genetic sex determination (homomorphic and heteromorphic sex chromosomes) and temperature sex determination are found in other sauropsids (except for tuatara), leading to high speciation rate and species diversification [31].

The crocodilian karyotype contains few large and many small chromosomes, and there is an absence of dot-shaped microchromosomes [1920]. On the contrary, the karyotypes of most squamate reptiles, tuatara, turtles, and birds contain macro- and microchromosomes [20]. Many chromosomal rearrangements might, therefore, be the result of the appearance or disappearance of microchromosomes, which reduced whole-chromosome homology among sauropsid chromosomes. The draft genome assemblies of chicken (Gallus gallus), Anolis lizard (Anolis carolinensis), Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis), American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), Indian gharial (G. gangeticus), Burmese python (Python molurus bivittatus), and king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) provided new perspectives on the comparative genomics of Sauropsida, which in turn facilitated extensive comparisons between genomic structures at a molecular level [323334353637]. Recent comparative gene mapping of several sauropsid species (Pelodiscus sinensis, Testudines; Crocodylus siamensis, Crocodilia; Gekko hokouenesis, Lacerta agilis, Elaphe quadrivirgata, Varanus salvator macromaculatus, Leiolepis reevesii rubritaeniata, Pogona vitticeps, and A. carolinensis, Squamata) with those of chicken revealed the extensive homology between avian and reptilian chromosomes, and suggested that the common ancestor of amniotes may have had many microchromosomes, whose linkages have been conserved among chickens and reptiles [252633, 38394041424344]. Comparison of the linkage homology between Archosauromorph and turtle chromosomes revealed that the macro- and microchromosomes of turtles are true counterparts of those of chicken [2526]. However, the comparative cytogenetic map of the Siamese crocodile (C. siamensis), i.e., the first cytogenetic map in the crocodilian lineage, revealed that genetic linkages of large chromosomes were also conserved in blocks on chromosome arms that corresponded to chicken macrochromosomal arms and/or entire macrochromosomes. The five largest bi-armed chromosomes of crocodile are derived by combinations of chromosome arms that differ from the chicken karyotype, while chicken microchromosomal genes are all localized to small chromosomes of the crocodile. This suggested that the Siamese crocodile karyotype resulted from two events that occurred in the crocodilian lineage: (1) centric fissions of bi-armed macrochromosomes in the ancestral Archosauromorph-turtle karyotype, followed by centric fusions between acrocentric macrochromosomes (new combination), leading to large chromosomes in crocodilians, and (2) repeated fusions of microchromosomes, which resulted in their disappearance and the appearance of a large number of small chromosomes [26].

Notably, chromosome size-dependent genomic compartmentalization is often found in birds and turtles but not in squamate reptiles, such as microchromosome-specific centromere repetitive sequences [4546474849505152]. This implied that the homogenization of centromeric repetitive sequences between macro- and microchromosomes did not predominantly occur in birds and turtles. However, no chromosome sized-specific centromeric repetitive sequences are found in crocodiles [21]. This suggested that chromosomal size-dependent genomic compartmentalization which is supposedly unique to Archosauromorph and turtles was probably lost with the disappearance of microchromosomes, followed by the homogenization of centromeric repetitive sequences among chromosomes in the crocodilian lineage after their divergence from birds around 240 MYA.

Chromosome Constitution in Crocodilian Lineage

Diploid chromosome numbers in crocodilians range from 30 to 42; most are 32 (Fig. 1) [1920]. Most karyotypes in crocodilians contain 4~5 large bi-armed chromosomes, 20~22 small bi-armed chromosomes, and 4~8 uni-armed chromosomes. However, genome rearrangements among members in the order rarely occurred, giving all crocodilians a fundamental number of 56~60, which suggested that the ancestral crocodilian karyotype was highly conserved [192021222326]. The chromosome number in Alligatoridae (Alligator 2n = 32, and Caiman, Melanosuchus, and Paleosuchus 2n = 42) is more varied than in Crocodylidae (Gavialis and Tomistoma 2n = 32, Mecistops 2n = 30, Osteolaemus 2n = 38, Crocodylus 2n = 30~34). Karyotypes of Caiman, Melanosuchus, and Paleosuchus show a large number of chromosome arms (NF = 60) [1920], suggesting that multiple centric fissions occurred after they diverged from Alligator. However, the largest chromosome variation is found in Crocodylus. The diploid chromosome number of 4 from 12 species (C. porosus, C. siamensis, Crocodylus palustris, and Crocodylus rhombifer) differs from 32, despite having the same fundamental number (58) (Fig. 1). This suggests that centric fusion/fission played a crucial role in the process of chromosomal rearrangements, leading to the formation of ordinal radiation in the lineage of crocodilians.

Crocodilian Phylogeny

Crocodilian systematics has been discussed at higher-level relationships based on morphological, paleobiogeography, and molecular data [1, 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,53,54,55]. However, no study has completely explained crocodilian relationships with their distribution and ecology. Most molecular crocodilian phylogeny contains 23 species (Fig. 1). The use of complete mitochondrial (mt) genome sequences and the mixture of several molecular loci (nuclear and mt genes) obviously provided the solution for at least three major conflicts of crocodilian clustering: (1) phylogenetic position of G. gangeticus and Tomistoma schlegelii; (2) relationship of Mecistops cataphractus and Crocodylus; and (3) position of C. siamensis, C. porosus, and C. palustris. Firstly, the position of G. gangeticus and T. schlegelii was controversial, since G. gangeticus was considered to be Gavialidae at the basal position of Crocodylia based on morphological evidence [153]. The molecular phylogenetic study of complete mt genome sequences and the mixture of several molecular loci clearly showed that G. gangeticus was a sister-taxon with T. schlegelii, and formed the sister group with the traditional Crocodylidae (Fig. 1) [8910111213141617]. This agreed with molecular sequence-based analyses of the CR1 retrotransposon which suggested that Alligatoridae (alligators and caimans) were sisters to all other crocodilians, and supported the G. gangeticus-T. schlegelii clade [56]. Therefore, only the two families (Alligatoridae and Crocodylidae) are now recognized to be within Crocodylia.

The most basal species within Crocodylus and relative species (Osteolaemus tetraspis) is the African sharp-nosed crocodile, M. cataphractus (formerly called Crocodylus cataphractus) [57]. Fossil evidence related to M. cataphractus appeared in the Miocene and Pliocene in Africa [585960], and implied that M. cataphractus was grouped within Crocodylus. However, molecular datasets suggested two relative species of two African crocodiles, M. cataphractus and O. tetraspis, being a sister group to the true crocodiles (Crocodylus) [4891011121314151617]. The last conflict issue concerned the position of C. siamensis, C. porosus, and C. palustris. In terms of molecular data, a complete mt genome of C. siamensis (DQ353946) showed it as a sister to C. porosus [24], whereas another mt genome sequence of C. siamensis (EF581859) related it to C. palustris [17]. Nonetheless, a molecular study based on the mixture of several molecular loci found in many C. siamensis individuals clearly showed that C. siamensis was sister to C. palustris and that C. porosus was sister to both species [16]. This agreed with karyological data that showed 2n = 30 for C. siamensis and C. palustris, and 2n = 34 for C. porosus (Fig. 1) [1920212226]. The Siamese crocodile sample sequenced by Ji et al. [24] was probably a hybrid between C. siamensis × C. porosus, frequently found in captivity in the crocodile industry [61]. The Siamese crocodile sample sequenced by Srikulnath et al. [17] was confirmed by karyotyping, and showed a chromosome number 2n = 30, a true C. siamensis. However, the relationship within Crocodylus remained unclear because of the position of Indo-Pacific crocodilians (Fig. 1). A molecular study based on complete mt genome sequences strongly indicated two major groups: (1) The Indo-Pacific species and (2) The African-New World (America) species. A molecular study with the mixture of several molecular loci comprising nuclear and mitochondrial genes suggested that the African-New World species grouped with C. porosus, C. palustris, and C. siamensis and was a sister clade with the group of Crocodylus mindorensis, Crocodylus novaeguineae, and Crocodylus johnstoni (Fig. 1) [16]. Multiple lines of evidence from biogeography and karyotypes have provided promising data to extensively discuss their evolutionary history.

Crocodilian Phylogeny Versus Chromosomal Rearrangements

According to the chromosome constitution of crocodilians, it would appear that chromosome changes evolved in parallel with the crocodilian relationship. Alligatoridae, which appeared in the early Tertiary, are considered to be the most primitive group in extant crocodilians [1]. There are two major crocodilians in Alligatoridae (Alligator and Caiman + Melanosuchus + Paleosuchus) generally found in the New World (America). This agreed with karyological data, which showed different karyotypic features in both chromosome number and fundamental number. Two Alligator species (A. mississippiensis and A. sinensis) still have the same karyotype form (2n = 32), but the karyotype of Caiman, Melanosuchus, and Paleosuchus, a sister clade of Alligator contains a higher chromosome number (2n = 42): a lower number of bi-armed chromosomes and a higher number of uni-armed chromosomes. This suggests that multiple centric fission occurred at the split of Alligator and Caiman + Melanosuchus + Paleosuchus, around 50~70 MYA before the middle of the Eocene (Fig. 1). This is more likely than an alternative explanation of the presence of centric fusion, because the karyotype of most crocodilians also exhibits 2n = 32. Interestingly, the total chromosome numbers of Caiman, Melanosuchus, and Paleosuchus are the same, but Paleosuchus contains a lower number of bi-armed and a higher number of uni-armed chromosomes, resulting in different fundamental numbers (Fig. 1). This suggests that Caiman + Melanosuchus and Paleosuchus evolved independently through at least one pericentric inversion or centromere positioning event, leading to ordinal radiation in two different lineages.

Two Alligator species (A. mississippiensis and A. sinensis), which exhibit the same karyotype form of 2n = 32, spread over more than one biogeography. A. mississippiensis is restricted to the Southeastern United States, whereas A. sinensis is restricted to China. Both species shared a common ancestor around 20~60 MYA (Fig. 1) [116]. This suggested the possibility of a geographic isolation process that played an important role in their evolutionary history. An overland route (presumably through Beringia) is the shortest distance from North America to Asia. Alligator probably moved to Asia during the warmer climate of the early Tertiary [16], based on the limitation of temperature and salt water tolerance [626364]. On the contrary, A. sinensis is the most cold-adapted of all living crocodilians, surviving the winter in burrows [65]. It might have moved into China during dramatic temperature changes. However, there was no evidence to support this idea until alligator fossils were found in Alaska [1].

The ancestral karyotype of crocodile is still retained in Crocodylidae. The karyotype of G. gangaticus (2n = 32) which resided in South-Asia, is also highly similar to that of Alligator [1920]. However, the karyotype of T. schlegelii (2n = 32), distributed around South-East Asia, contains lower numbers of bi-armed chromosomes and higher numbers of uni-armed chromosomes, and the fundamental numbers of these two species are different. This suggests the presence of pericentric inversion or centromere positioning, which probably occurred in T. schlegelii after it diverged from G. gangaticus around 15~35 MYA in the late Tertiary. In Crocodylus and relative species (M. cataphractus and O. tetraspis) lineage, the karyotype of M. cataphractus showed a lower total chromosome number with higher bi-armed chromosomes than those of T. schlegelii, despite having the same fundamental number (58), suggesting that the increase of bi-armed chromosomes is the result of centric fusion among the ancestral types of acrocentric chromosomes (Fig. 1). By contrast, the karyotype of O. tetraspis showed a higher total chromosome number with higher uni-armed chromosomes, but lower bi-armed chromosomes than those of G. gangaticus, T. schlegelii, and M. cataphractus [1920]. This suggests that at least multiple centric fissions occurred after O. tetraspis diverged from G. gangaticus, T. schlegelii, and M. cataphractus around 14~37 MYA.

Karyotypes resembling (2n = 32) T. schlegelii are also found in Crocodylus. This suggests that both T. schlegelii and Crocodylus share the same karyotypic feature which is derived from G. gangaticus and Alligator as a common ancestor of Crocodylia. By contrast, Crocodylus, only one genus in crocodilians, shows variation of chromosome number and chromosome morphology, in spite of the same chromosome number. This suggests that karyotype evolution occurred in Crocodylus, and subsequently radiated karyotypic forms in different species, during the period of crocodilian extinction around 9~16 MYA in the middle of the Miocene (Fig. 1) [16]. It is likely that after climate optimum in mid-Miocene, speciation process of Crocodylus was conducted along with global cooling and glaciation until the end of Pliocene, whereas other crocodilians underwent massive extinction [64]. The role of chromosome changes with species diversity is also found in other species during the same period, such as New World rodent (Calomys) [66] or African rodent (Tatera) [67]. Interestingly, the chromosome structure of Crocodylus species is likely conserved within the genus. This agreed with the presence of hybridization in captivity, often found in Crocodylus species. It would appear that all species from the genus have the potential to hybridize and produce fertile offspring. Examples of such events have been reported in both sympatric [6869] and allopatric species [61]. C. siamensis with chromosome number 2n = 30 has also hybridized with C. porosus with chromosome number 2n = 34. Chavananikul et al. [70] found that interspecific breeding of C. siamensis and C. porosus produced F1 hybrids (2n = 32) and F2 offspring with 2n = 32. This suggested hybrid viability, despite different chromosome numbers in the parent generation. This probably results from genome features that are still similar and not diverse in a short period of time in Crocodylus. Thus, the study of hybrid viability, homologous recombination, and meiotic segregation mechanisms may be critical to understand their genome evolution. However, the relative stability of Crocodylus genomes contributes to the lack of postzygotic reproductive isolation mechanisms, which is a fascinating aspect of crocodilian evolutionary biology, and rejects the traditional biological species concept. Other evidence of high conservation in chromosome structure is satellite DNA (stDNA) at the centromeric region on crocodilian chromosomes. Two stDNAs (CSI-HindIII-S and CSI-HindIII-M) isolated from C. siamensis and localized to centromeric regions of all chromosomes, except for chromosome 2, were highly conserved throughout several crocodilian species (Crocodylus niloticus, T. schlegelii, G. gangeticus, A. mississippiensis, A. sinensis, Caiman crocodilus, and Caiman latirostris) [21]. This suggested that CSI-HindIII sequences were contained in the karyotype of a common ancestor of Crocodylia. However, the evolutionary history of Crocodylus species recently diversified during a period of crocodilian extinction. This tallied with the evidence of a centromeric stDNA (CSI-DraI), which was also isolated from C. siamensis and localized to chromosome 2, and four pairs of small-sized chromosomes, were recognized in the genus Crocodylus but not in other crocodilians (Lapbenjakul et al. unpublished data) [21]. This suggested that CSI-DraI differentiated as a very rapidly evolving molecule in the Crocodylus lineage when crocodilian extinction began, and the molecular structure of centromeric regions of Crocodylus evolved independently from other crocodilians.

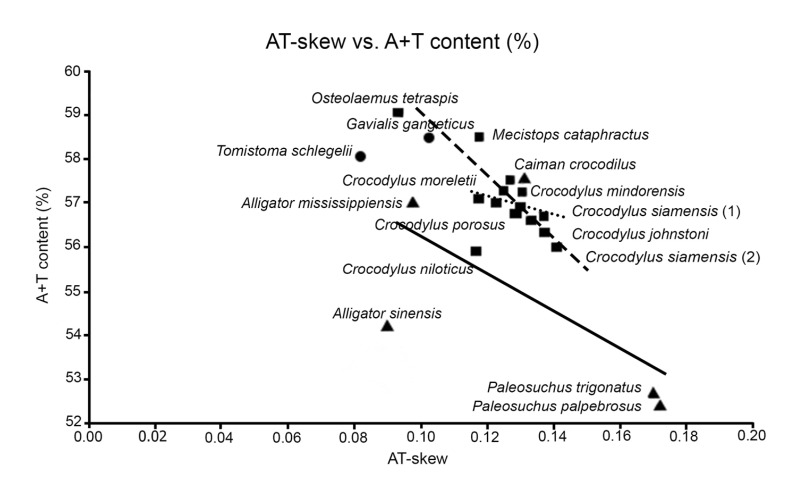

Within the Crocodylus lineage, molecular sequence analyses suggested highly recent radiation in this crocodilian group (Fig. 1) [16]. The relationship of A + T content (%) and AT-skew of the mtDNA genome also agreed with this indication as a high correlation between A + T content and AT-skew in many Crocodylus species but low correlation in other crocodilians (Fig. 2), suggesting that the bias of base substitution that occurred in the Crocodylus lineage did not have time to eminently alter the base composition of mtDNA genome as in other crocodilian divergences [17]. Traditionally, Crocodylus was considered to have originated in Africa during the Cretaceous [71], and their current distribution has resulted from continental drift [72]. However, recent molecular data and fossil records in Asia suggested that the Indo-Pacific was the place of origin of Crocodylus species [16]. They then migrated to the land based on two hypotheses: (1) dispersion from Indo-Pacific to the New World, followed by dispersion to Africa; and (2) dispersion from the Indo-Pacific into Africa, followed by dispersion to the New World.

AT-skew versus A + T content (%) of complete mitochondrial (mt) DNA genomes in Crocodylia. Values are calculated on heavy strands for full length of mtDNA genomes from 23 crocodilians [7911121314151724]. The x-axis indicates the skew values, the y-axis provides the A + T content (%). The wide fine dashed line indicates the Crocodylus relation between AT-skew versus A + T content, whereas the solid line and the dashed line display the Alligatoridae and Crocodylidae relations, respectively.

The Indo-Pacific to the New World

This hypothesis suggested the trans-Pacific dispersion of Crocodylus from the Indo-Pacific to the New World around 8~12 MYA, followed by moving to Africa from the New World around 4~8 MYA. This hypothesis was supported by at least three pieces of evidence: the presence of fossil crocodilian records within Asia and the New World [173], the distribution of the saltwater crocodile C. porosus, and the extinct Crocodylus lineage in the Pacific islands. Molecular phylogenetic placement by Oaks [16] showed the sister group of C. porosus, C. palustris, and C. siamensis clade and New World Crocodylus species. However, it is hard to explain how C. porosus (2n = 34) and/or C. palustris and C. siamensis (2n = 30) migrated and evolved into New World species (2n = 32), whose karyotype retains an ancestral form. It is likely that the C. porosus karyotype resulted from the proto-Crocodylus karyotype by centric fission, and the New World species karyotypes experienced centric fusion reversibly again from C. porosus.

The Indo-Pacific to Africa

The dispersion of Crocodylus from the Indo-Pacific into Africa occurred 8~12 MYA, followed by trans-Atlantic dispersion to the New World 4~8 MYA. The crocodilian fossil record also showed that Crocodylus species were present in Southern Europe and Northern Africa during the late Miocene with warmer and wetter climate across this region [747576]. This might have allowed the Crocodylus species to move from Asia into Africa without requiring long-distance marine dispersion. It is likely that the species group comprising C. mindorensis, C. novaeguineae, and C. johnstoni, positioned to the basal node of the phylogenetic tree as suggested by Oaks [16] might be the origin of the Indo-Pacific species. This agreed with karyological data of Crocodylus, which showed a diploid chromosome of C. mindorensis, C. novaeguineae, C. johnstoni (Indo-Pacific species) C. niloticus (African species), Crocodylus moreletii, Crocodylus acutus, and Crocodylus intermedius (New World species) to be 32. Crocodylus maintained the broad African and Indo-Pacific distribution, and then split between the African + New World species clade and the remaining Indo-Pacific species around 4~8 MYA.

The latter hypothesis is more likely, based on the most parsimonious explanation with karyological data. This also agreed with the phylogenetic relationship of some Nile crocodiles (C. niloticus), complete mt genome sequences placed with those of New World species, and the exclusion of Nile crocodiles from other populations [15]. The two earliest fossils of C. niloticus and New World species appear during the Pliocene [73], and C. niloticus has lingual salt-excreting glands. Moreover, some populations of C. niloticus occupy estuarine habitats [63]. This suggested that an African crocodilian crossed the Atlantic recently, when this oceanic barrier was hundreds of miles wide [1577]. The presence of trans-Atlantic dispersion is also found in other vertebrates [78].

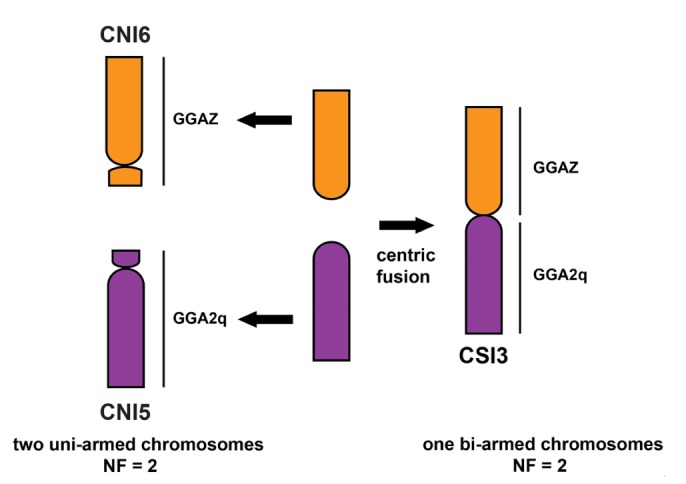

The molecular placement of C. porosus, C. palustris, and C. siamensis is expected to position as the sister to African + New World species (Fig. 1). The ancestral karyotype feature is still retained in African and New World crocodiles. Comparison of the data of chromosome painting in C. niloticus and chromosome maps with functional genes in C. siamensis, revealed that five large chromosomes of C. siamensis correspond to six large chromosomes of C. niloticus [2326]. C. siamensis chromosome 3 (CSI3) is metacentric, and C. niloticus chromosome 5 (CNI5) and CNI6 are acrocentrics. CSI3p corresponds to CNI6, and CSI3q to CNI5. This suggests that bi-armed chromosomes CSI3 are the results of centric fusion among the ancestral types of acrocentric chromosomes (Fig. 3). A centric fusion event is more likely because CNI5 and CNI6 are considered the prototypes in the lineages of Crocodylus, based on the evidence of karyotype and chromosome constitution with other crocodilians [1920]. The karyotype of C. palustris and C. siamensis (2n = 30) probably resulted from one centric fusion of two acrocentric chromosomes from ancestral Crocodylus species from the Indo-Pacific species, leading to the reduction of uni-armed chromosomes in both two species. By contrast, karyotype of C. porosus (2n = 34) might result from one centric fission of large bi-armed chromosomes from ancestral Crocodylus species, leading to the increase of acrocentric chromosomes.

Schematic representation for the process of chromosomal rearrangements that occurred among Crocodylus siamensis chromosomes (CSI) 3, and Crocodylus niloticus chromosomes (CNI) 5 and 6. Chromosome homologies with the chicken (Gallus gallus) are obtained from the following sources: C. siamensis from Uno et al. [26] and C. niloticus from Kasai et al. [23], and are shown to the right of the chromosomes. Homologous chromosomes and/or chromosome segments are shown using the same color. Arrows indicate the directions of the chromosomal rearrangements. NF, fundamental number.

Simultaneously, the molecular placement of New World species is also controversial, considering complete mt genome sequences and the mixture of several molecular loci, in which C. rhombifer and C. moreletii are positioned at a basal or recent clade (Fig. 1). The karyotype data of C. niloticus and New World species (C. acutus and C. intermedius) suggest that the karyotype of C. moreletii and C. rhombifer is probably located at the recent clade of New World species. The karyotype of C. moreletii contains a lower number of bi-armed chromosomes and a higher number of uni-armed chromosomes, compared to C. acutus and C. intermedius, making the fundamental numbers of these three species different. This suggests that the presence of pericentric inversion or centromere positioning has probably occurred in the ancestral karyotype of C. moreletii after divergence from C. acutus and C. intermedius around 3~7 MYA during the Pliocene. By contrast, the karyotype of C. rhombifer contains 2n = 30, and centric fusion might have occurred in the ancestral karyotype, leading to the reduction of acrocentric chromosomes in C. rhombifer.

Conclusions

The role of chromosomal rearrangement led us to understand the evolutionary history of crocodilians to sauropsids and within the crocodilian lineage. It is likely that centric fusion/fission is a key evolutionary force of crocodilian diversity. The Crocodylus group is considered to have variation of karyotypic features, comprising 2n = 30, 32, and 34, whereas the chromosome number of the remaining group was fixed in each lineage. The Crocodylus species originated from an ancestor in the Indo-Pacific, and rapidly radiated and dispersed around the globe during a dire period in crocodilian extinction. Moreover, Crocodylus species probably underwent multiple transoceanic dispersions from the Indo-Pacific to Africa and to the New World. Karyotype analysis also supported the direction of molecular phylogenetic placement in crocodilians, which was previously controversial. The study also provided insight into the phylogenetic hierarchy of genome evolution in crocodilians.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute (KURDI) and the Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, Thailand. We are also grateful to Amara Thongpan (Kasetsart University) and Yosapong Temsiripong (Sriracha Moda Co., Ltd, Thailand) for helpful discussions.