Heritability Estimated Using 50K SNPs Indicates Missing Heritability Problem in Holstein Breeding

Article information

Abstract

Previous studies in Holstein have shown 35% to 51.8% heritability in milk production traits, such as milk yield, fat, and protein, using pedigree data. Other studies in complex human traits could be captured by common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and their genetic variations, attributed to chromosomes, are in proportion to their length. Using genome-wide estimation and partitioning approaches, we analyzed three quantitative Holstein traits relevant to milk production in Korean Holstein data harvested from 462 individuals genotyped for 54,609 SNPs. For all three traits (milk yield, fat, and protein), we estimated a nominally significant (p = 0.1) proportion of variance explained by all SNPs on the Illumina BovineSNP50 Beadchip (h2G). These common SNPs explained approximately most of the narrow-sense heritability. Longer genomic regions tended to provide more phenotypic variation information, with a correlation of 0.46~0.53 between the estimate of variance explained by individual chromosomes and their physical length. These results suggested that polygenicity was ubiquitous for Holstein milk production traits. These results will expand our knowledge on recent animal breeding, such as genomic selection in Holstein.

Introduction

New-generation sequencing technologies have substantially enhanced the development of genomic tools to assist in breeding decisions. Among many techniques, genotyping technologies have enabled breeders or researchers to identify DNA regions or quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with a particular phenotypic trait of domesticated animals. Especially, several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and QTL associated with Holstein complex traits, including economic traits related to milk production, were investigated in the approximate 10-year wave of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) [123]. In the near past, researchers discovered genetic markers and created marker panels for use in performing marker-assisted selection (MAS). Although MAS provided a first genomic approach to achieve breeding goals to animal breeders, the domesticated animal genome in MAS was taken lightly with narrow perspectives. MAS is restricted when it comes to predicting animal capacity, as it depends on a small number of QTLs that are tagged by markers associated with each trait [4]. Additionally, the gap between the proportion of phenotypic variance accounted for by the top SNPs that reach genome-wide significance level in a GWAS and the heritability estimated from pedigree analyses remained unexplained for most complex traits of human. This was called the missing heritability problem [5], explanations to which have been debated in the field [6].

Recent studies using whole-genome estimation approaches demonstrated that a large proportion of heritability for complex traits of humans can be captured by all common SNPs on current genotyping arrays. It implies that there are a large number of variants with an effect that is too small to pass the stringent genome-wide significance level. In animal breeding, genomics selection (GS) has been developed to overcome restriction factors of MAS; it has covered a large number of variants containing small effects. The fundamental difference between MAS and GS as important animal selection tools is that scale GS embraces a much larger number of markers than MAS in predicting animal capacity. GS uses a dense set of markers from across the entire genome to use all markers containing SNPs with small effects. This feature gives GS a profound advantage over MAS.

For predictions based on genomic data for humans, a previous study has already estimated the proportion of phenotypic variance. It was elucidated by the common SNPs all together on a genotyping array for a range of quantitative traits in a large homogenous human sample, using the whole-genome estimation and partitioning approaches [7]. The novelty of our research lies in animal capacity prediction based on genomic data due to the fact that animal evaluation is a core content in the breeding industry. Finally, to conduct our animal breeding research on polygenic inheritance, which was likely to be ubiquitous for complex Holstein traits associated with milk production traits, the genomic selection technique was performed along with various different analyses.

Methods

Korean Holstein data

This study used 462 Holsteins from Korea, and they had information on three phenotypes related to milk production for parity 1 (Fig. 1). Three traits used in this study were milk yield, milk fat, and milk protein; 339 of 462 Holsteins in records of parity 1 had records of parity 2. The individuals produced milk in 63 farms and were born in 2005 to 2012. All candidates were measured for a range of quantitative traits through public surveys for livestock improvement.

Genotyped and imputed data

The genomic DNAs were isolated from snivel by using the nasal collection kit and were genotyped with 54,609 SNPs on the Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip. We excluded the SNPs with a missingness rate of 0.05, minor allele frequency (MAF) 0.01, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test p-value 10-6 using PLINK [8]. Then, we removed SNPs on the sex chromosome and retained 41,099 autosomal SNPs for further analysis. After this quality control, 462 Holstein genomic data had been imputed using BEAGLE [9].

Estimating and partitioning genetic variance using SNP data

We estimated the genetic relationship matrix (GRM) between all pairs of individuals from all genotyped SNPs For each trait, we then estimated the variance that can be captured by all SNPs using the restricted maximum likelihood approach in a mixed linear model:

where y is a vector of phenotypes, b is a vector of fixed effects with its incidence matrix X, and gG is a vector of aggregate effects of all SNPs.

AG is the SNP-derived GRM, and σ2G is the additive genetic variance. The proportion of variance explained by all SNPs is defined as

σ2p is the phenotypic variance. Details of the model and parameter estimation have been described elsewhere [1011]. When we estimated genetic variance using SNP data, we have to consider seasonal effects (winter, December–February; spring, March–May; summer, June–August; and autumn, September–November based on birth date) as environmental effects, because milk production traits are closely related to season. Then, we performed ANOVA test to investigate the relationship between each trait (parity 1 and 2) and seasonal effect. Milk fat had only a close relation to season in the ANOVA test of both parity 1 (p = 0.0267) and 2 (p = 0.000432). We counted on seasonal effect in only the analysis including milk fat. In addition, using the same method as above but allowing multiple genetic components to be fit simultaneously in the model, we partitioned h2G into the contributions of genic (h2Gg) and intergenic (h2Gi) regions of the whole genome across all traits. The genic regions were defined as ±0 kb of the 3' and 5' untranslated regions (UTRs). A total of 13,297 SNPs were located within the boundaries of 7001 protein-coding genes for this definition (±0 kb). The total length of the 7001 protein-coding genes was approximately 585 Mb, which covered 21.91% of the genome. We performed these estimating and partitioning genetic variance using SNP data through GCTA [11].

Results

We used the data from the Korea Holstein population. These data were collected from 462 cows recruited from 63 farms in South Korea, genotyped at 54,609 SNPs on the Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip. There were 462 individuals and 41,099 autosomal SNPs after quality control (Methods section). All individuals were measured for three traits (milk yield, milk fat, and milk protein), which were related to milk production. The phenotypic correlations between pairwise traits are visualized in Supplementary Fig. 1. Correlations between milk yield and milk protein were much stronger than other pairwise comparisons.

We estimated the proportion of variance explained by fitting all SNPs in a mixed linear model for each of the three traits. In general, there was a substantial amount of variance explained by all autosomal SNPs after quality control on the Illumina BovineSNP50 BeadChip (σ2G) for three traits of the records of two parities, with a mean of 43.51% (a range from 36.3 to 47%) across all three traits of the records of two parities (Table 1). In the records, the estimate of h2G was non-zero and reached the nominal significance level (likelihood ratio test, p = 0.05). We compared the estimates of h2G with the narrow-sense heritability h2, estimated from pedigree analyses in the literature based on Canada Holstein. The value of h2G was similar to h2 from pedigree analysis in the literature, and all common SNPs explained most (average, 43.51%; range from 36.3% to 47%) of the narrow-sense heritability (average, 41.38%; range from 36.3% to 47%), despite the estimates of h2 being from different country populations (Table 1). In contrast, when we performed a genome-wide association analysis in the same sample, we tried to identify genome-wide-significant (Bonfferoni correction p = 0.05) SNPs for three traits of parity 1. Three SNPs and one SNP were significant in milk yield and fat, respectively, and there were no significant SNPs for milk protein (Supplementary Fig. 2). We hypothesized that there was a major reason for only a few significant large-effect SNPs associated with Holstein traits related to milk production. First of all, many SNPs with small effects affected the three traits related to milk production. Second, according to previous studies, there are many common variants associated with the traits in humans at a nominally significant level, but their effect sizes are too small to be genome-wide-significant [7].

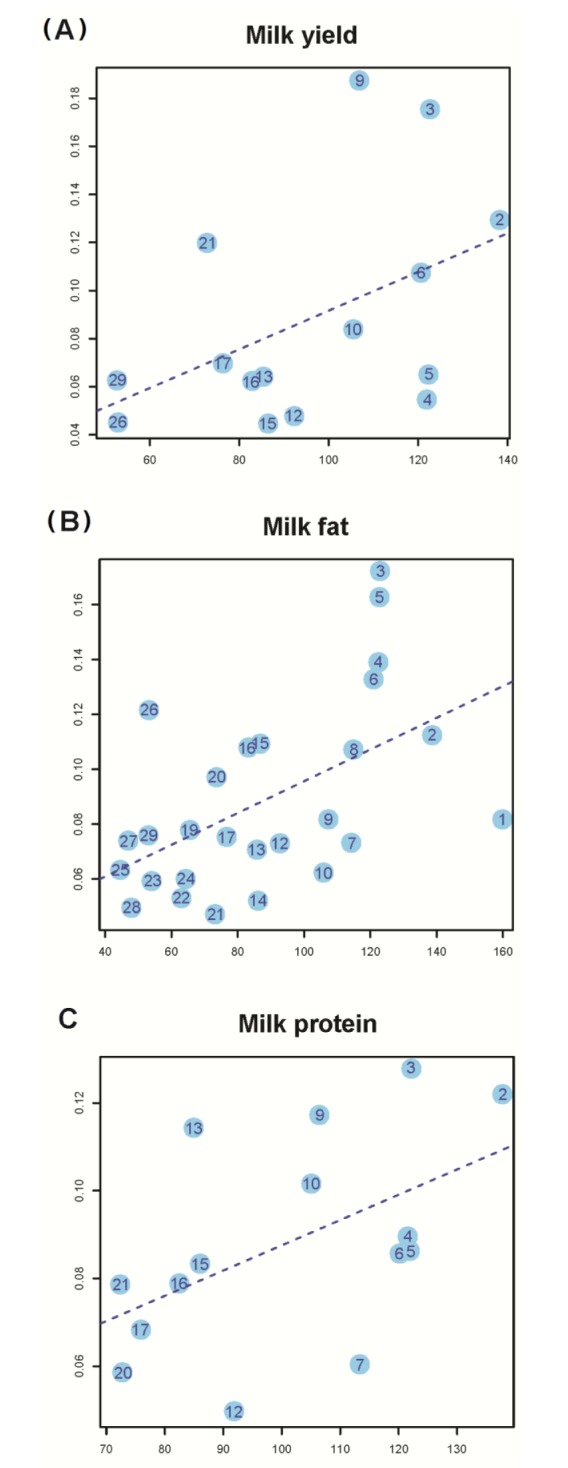

Using the same method as above but allowing multiple genetic components to be fit simultaneously in the model, we then partitioned h2G into the contributions of individual chromosomes for each of the three traits of two parities and plotted the estimate of variance explained by each chromosome (h2C) against the chromosome length for each trait. In a previous study, no linear correlation between h2C and chromosome length for any particular traits was observed for most traits in humans as strongly as shown in the other studies. Then, the average value of estimates of h2G over all of tens traits to reduce the sampling error variance, and the average estimated h2C was strongly correlated with chromosome length. However, we dealt with only three traits related to milk production, and we aimed to identify a linear correlation between h2C and chromosome length for each trait. The squared correlation between h2C and chromosome length using trait information of parity 1 was 0.46, 0.532, and 0.509 for milk yield, fat, and protein, respectively (Fig. 2). The regression slope of the proportion of the genetic variance attributed to each chromosome on the proportion of the genome represented by each chromosome was significant (p<0.1), suggesting a proportional relationship between genome length and genetic variance in Holstein. Consistent results were achieved from myriad genetic variants, each possessing a small effect throughout the widespread whole genome in Holstein.

Proportion of variance attributed to each chromosome of three traits of parity 1 against chromosome length. We show proportion of variance of each chromosome, which is significant based on likelihood test (p-value<0.1). (A) Milk yield (slope = 8.05 E-04, S.E = 4.31 E-04, p-value = 8.46 E-02). (B) Milk fat (slope = 5.79 E-04, S.E = 1.84 E-04, p-value = 4.26 E-03). (C) Milk protein (slope = 5.75 E-04, S.E = 2.97 E-04, p-value = 5.24 E-02).

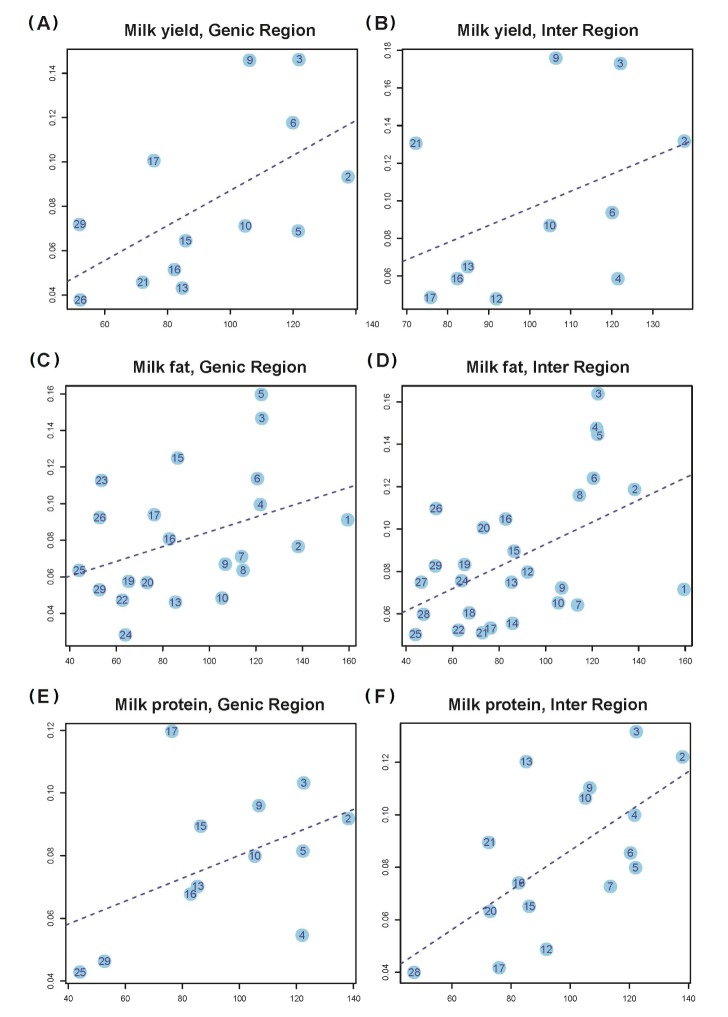

In addition, we partitioned h2G into the contributions of genic (h2Gg) and intergenic (h2Gi) regions of the whole genome (Methods section). We estimated the variance explained by the genic (h2Cg) and intergenic (h2Ci) regions of each chromosome. The numbers of genic and intergenic SNPs on each chromosome are presented in Supplementary Table 2. We showed that the variance explained by the genic (intergenic) regions on each chromosome is also proportional to the total length of the genic (intergenic) regions (Fig. 3).

Estimates of the variance explained by all SNPs in genic (intergenic) regions for 3 traits (a, b, and c indicate milk yield, fat, and protein, respectively) against length of genic (intergenic) DNA. Shown in panels (A), (C), and (E) are the results for the genic SNPs, and shown on panels (B), (D), and (F) are the results for intergenic SNPs, under the assumption that genic regions is Wor0 Kb of UTRs. (A) Milk yield, genic region (slope = 7.89 E-04, S.E = 3.30 E-04, p-value = 3.56 E-02). (B) Milk yield, intergenic region (slope = 9.11 E-04, S.E = 6.70 E-04, p-value = 2.07 E-01). (C) Milk fat, genic region (slope = 4.04 E-04, S.E = 2.20 E-04, p-value = 8.01 E-02). (D) Milk fat, intergenic region (slope = 5.23 E-04, S.E = 1.78 E-04, p-value = 7.02 E-03). (E) Milk protein, genic region (slope = 3.66 E-04, S.E = 2.24 E-04, p-value = 1.34 E-01). (F) Milk protein, intergenic region (slope = 7.53 E-04, S.E = 2.24 E-04, p-value = 7.20 E-03).

Discussion

Previous studies using the whole-genome estimation approach have shown that common SNPs explicate a large proportion of heritability for traits in human [1012]. The reason why GWASs in this field have not yet identified all common SNPs that contain information on the amount of variation is mainly that many peculiar effects are too small to pass the stringent genome-wide significance level. Therefore, we hypothesized that inheritance of Korean Holstein milk production traits would consist of a lot of genetic variants with small effects. Finally, we estimated and partitioned the genetic variance that met certain conditions, tagged by all common SNPs for three complex traits related to milk production and showing ubiquitous polygenic inheritance of Korean Holstein. The estimates of h2G for three traits were different from 0 at the significance level (p<0.1). The estimate of h2G for milk yield of parity 1 was 43.0% (SE = 10.3%), which was smaller than the estimate from a study in Canada (h2G = 52%) [13]. There could be three possible reasons: (1) There is a difference in the reference population size between Korea and Canada. In fact, Koreans import a lot of Canada Holstein semen, but the present reference population is smaller than Canada. (2) The Korean environment is different from Canada. (3) We can consider only one environmental effect (season) due to data size in this study. The estimate for milk fat (h2G = 47.0%, SE = 10.1%) and protein (h2G = 44.3%, SE = 10.2%) in Korea was larger than in Canada (fat h2G = 36.9%, protein h2G = 42.3%).

It is demonstrated by the genome partitioning analysis that there was a significant linear relationship between the estimates of variance explained by individual chromosomes and chromosome length (Fig. 2). If we define the genic region as ±0 kb of the UTRs, the correlation between variance explained and chromosome length was stronger in the intergenic regions than in the genic regions (Fig. 3). A previous study showed by a number of analyses that the result in this was driven neither by the difference between the number of SNPs in genic regions and in intergenic regions nor by the difference in MAF distribution between genic and intergenic SNPs [7]. If trait-associated genetic variants are enriched in functional elements, such as introns and UTRs, and diluted in exons, the relationship between the explained variance and DNA length will be attenuated in the genic region, as in human. However, it could possibly be just a sampling problem. Because our data size was smaller than our expectancy, some chromosomes did not reach the significance level (p = 0.01) in the genome partitioning analysis. In the genome partitioning analysis for milk yield using SNPs in the intergenic region and milk protein using SNPs in the genic region, the linear regression results were also insignificant, and we could identify some outliers. Moreover, when these outliers were removed, the linear regression results were significant (E in Fig. 3). We hypothesize that some chromosomes could have a slightly larger effect than our expectation, based on the fitted line in special cases (chromosome 17 or 4 in milk protein).

We showed by whole-genome estimation and partitioning analyses that Holstein milk production traits appeared to be highly polygenic, which means that there were a large number of genetic variants segregating in the population with a small effect widely distributed across the whole genome. All common SNPs expressed most of the heritability on average over all 3 traits analyzed in this study. The slight, remaining unexplained heritability could be due to causal variants, including common and rare ones that are not well tagged by SNPs on this Illumina SNP chip, or possibly because the heritability was over-estimated in the pedigree study. In conclusion, heritability consists of many variants with small effects for Holstein milk production traits in Korea. Overall, this research will become a cornerstone for genomic selection applications in animal breeding.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by a grant from the Next-Generation Biogreen 21 Program (Project No. PJ01134905), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data, including two figures and two tables, can be found with this article online at http://www/genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-13-146-s001.pdf.

Supplementary Table 1

Numbers of genic and intergenic SNPs on each chromosome

Supplementary Table 2

Variance explained by all the genic and intergenic SNPs on individual chromosomes for the 3 traits

Supplementary Fig. 1

All pairwise phenotypic correlation of the three traits related to milk production. (A) Parity 1 data. (B) Parity 2 data.

Supplementary Fig. 2

Manhattan plot of genome-wide association studies results for three traits of parity 1 (milk yield, milk fat, and milk protein, respectively).