Elucidation of the Inhibitory Effect of Phytochemicals with Kir6.2 Wild-Type and Mutant Models Associated in Type-1 Diabetes through Molecular Docking Approach

Article information

Abstract

Among all serious diseases globally, diabetes (type 1 and type 2) still poses a major challenge to the world population. Several target proteins have been identified, and the etiology causing diabetes has been reasonably well studied. But, there is still a gap in deciding on the choice of a drug, especially when the target is mutated. Mutations in the KCNJ11 gene, encoding the kir6.2 channel, are reported to be associated with congenital hyperinsulinism, having a major impact in causing type 1 diabetes, and due to the lack of its 3D structure, an attempt has been made to predict the structure of kir6.2, applying fold recognition methods. The current work is intended to investigate the affinity of four phytochemicals namely, curcumin (Curcuma longa), genistein (Genista tinctoria), piperine (Piper nigrum), and pterostilbene (Vitis vinifera) in a normal as well as in a mutant kir6.2 model by adopting a molecular docking methodology. The phytochemicals were docked in both wild and mutated kir6.2 models in two rounds: blind docking followed by ATP-binding pocket-specific docking. From the binding pockets, the common interacting amino acid residues participating strongly within the binding pocket were identified and compared. From the study, we conclude that these phytochemicals have strong affinity in both the normal and mutant kir6.2 model. This work would be helpful for further study of the phytochemicals above for the treatment of type 1 diabetes by targeting the kir6.2 channel.

Introduction

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus is a major health problem worldwide. In case of type 1 diabetes, the body is unable to produce insulin due to the autoimmune destruction of the beta-cells in the pancreas [1], and insulin injection is the only known preventive measure in this case [2]. Most of the anti-diabetic drugs of synthetic origin have serious adverse effects; therefore, phytochemicals and plant extracts with anti-diabetic properties have been tested both in vivo and in vitro as alternatives for diabetic treatments [3]. Phytochemicals, such as curcumin (Curcuma longa), genistein (Genista tinctoria), piperine (Piper nigrum), and pterostilbene (Vitis vinifera), are reported to have potent anti-diabetic properties. Curcumin, when tested in diabetic animals, exhibited a good sign for the prevention and treatment of diabetic encephalopathy [4]. Genistein also plays important roles in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in type 1 diabetes by down-regulating G6Pase, PEPCK, fatty acid β-oxidation, and carnitine palmitoyl transferase activities while up-regulating malic enzyme and glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase activities in the liver, with preservation of pancreatic β-cells. The supplementation of genistein is helpful for preventing insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus onset [5] and piperine, an alkaloid, has also been reported to possess potential anti-diabetic effects [6]. Experimental results suggested the antiglycemic effects of pterostilbene in an induced rat model of hyperglycemia. Therefore, the antioxidant and antihyperglycemic activities of pterostilbene may confer a protective effect in preventing diabetes [7]. Several receptors (insulin-like growth factor receptor, glucose transporter, and kir6.2) and their associated signaling pathways have been elucidated and are involved in glucose regulation and diabetes. But, a significant gap still remains as to making the choice of the drug against the target receptor in the disease condition. Kir6.2, a major subunit of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel, an inward-rectifying potassium ion channel, is an integral membrane protein that allows K+ to flow from the outside of the cell to the inside, which is controlled by G-proteins associated with sulfonylurea receptor (SUR), to constitute the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. During glycolysis, an increase in the ATP/ADP ratio blocks KATP channels, causing membrane depolarization, and helps in opening the voltage-dependent calcium channel, which facilitates the influx of calcium, triggering the exocytosis of insulin. Mutations in the two subunits of SUR1 and kir6.2 result in the opening of the pancreatic KATP channel and permanent closing of the calcium channel, thus blocking insulin exocytosis. Mutations in KCNJ11, the gene encoding the channel, are reported to be associated with congenital hyperinsulinism [8, 9]. Ten possible mutations affecting the regular mechanism of kir6.2 [8, 10, 11] have been identified as probable causes of type 1 diabetes. Due to the unavailability of the crystal structure of kir6.2 protein, an attempt was made here to predict both the secondary and tertiary structures using in silico approach. The objective of the current investigation is to describe atomic interactions and the inhibitory effect between both wild-type and mutant models of kir6.2 with phytochemicals, such as curcumin, genistein, piperine, and pterostilbene, computationally.

Methods

Structure prediction and model validation of kir6.2 (wild, mutant)

The primary sequence of kir6.2 (entry name, KCNJ11_HUMAN) was retrieved from SWISS-PROT/UniProt KB (ID, Q14654). The secondary structure of both wild-type and mutant kir6.2 was predicted using Discovery Studio 3.5. The tertiary structure prediction for kir6.2 models (both wild type and mutant) were performed using the protein fold recognition server Phyre2 (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/) with 100% confidence. The predicted models were energetically minimized in ModRefiner (http://zhanglab.ccmb.umich.edu/ModRefiner/) to draw the initial starting models closer to their native state, in terms of hydrogen bonds, backbone topology, and side chain positioning. The coordinates of the predicted model of kir6.2 were submitted in Protein Model DataBase (http://bioinformatics.cineca.it/PMDB/). Structural validation was done in Procheck and Errat2 of the Saves web server (http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/SAVES_3/). Protein model quality was checked in the protein structure analysis tool ProSA (http://prosa.services.came.sbg.ac.at/prosa.php). Energetically minimized structures of both kir6.2 models were visualized and superimposed in Discovery Studio 3.5.

Molecular docking of kir6.2 model with phytochemicals

Molecular docking between kir6.2 models and phytochemicals was accomplished using the AutoDock-4.2 algorithm (http://autodock.scripps.edu/). Kollman united atom charges, solvation parameters, and polar hydrogens were added into the kir6.2 PDB files for the preparation of the protein in the docking simulation. Chemical structures of phytochemicals having anti-diabetic properties were extracted from the Pubchem (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound) database of the National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) web server (Supplementary Fig. 1) in SDF format and converted to three-dimensional structures in PDB format using Discovery Studio 3.5. Ligand molecules were prepared by choosing the root and restricting the number of torsion within a minimum range. AutoDock requires precalculated grid maps, one for each atom type present in the flexible molecules being docked, and it stores the potential energy arising from the interaction with rigid macromolecules. One hundred runs of blind dockings were performed for all inhibitors with both the wild-type and mutant protein model of kir6.2. Then next round of docking was performed by setting a grid of 98, 100, and 62 points in the x, y, and z directions, respectively, in the ATP-binding site of kir6.2 [12] for both models by applying the Lamarckian genetic algorithm. The best poses of docking during both rounds were compared and reported with the binding energy reported for each case. The visualization and analysis were performed using Discover Studio 3.5 package.

Results

Structure prediction and validation of kir6.2 structural models

The primary sequence of kir6.2 (UniProt ID, Q14654) is a transmembrane protein with 390 amino acid residues. Ten mutations [10] were introduced in the primary sequence of kir6.2 for mutant model prediction purposes. Two tertiary structural models were predicted for both wild (template PDB ID, 3JYC) and mutant-type kir6.2 (template PDB ID, 3SYA) separately using Phyre2 [13] with 100% confidence, followed by energy minimization using ModRefiner [14] web server. The structural model of kir6.2 is publically available in the Protein Model DataBase (PMID ID, PM0079770). The quality of the model was compared with three existing models of kir6.2 available in the Protein Model Portal (http://www.proteinmodelportal.org/query/uniprot/Q14654). The first model available in the Protein Model Portal was done for the amino acid region of 179-351, taking template PDB ID 1U4F, chain C with a 53% identity score. However, this model is not complete in comparison to the present predicted model of kir6.2 (PMID, PM0079770), which is modeled from amino acid region 33-358. The second and third models available are almost complete and modeled for the same amino acid region as in the present model of wild kir6.2. While comparing the quality with all experimentally determined protein chains in the current PDB using the ProSA web server [15] by means of a significant statistical score (z-score) in terms of folding energy, the second and third models had a z-score computed in the ProSA web server of -5.16 (Supplementary Fig. 2B) and -5.6 (Supplementary Fig. 2C), respectively, while in comparison, the current model had a good folding energy score-i.e., z-score of -5.96 (Supplementary Fig. 2A). The overall quality factors of these two models were also compared with the current predicted model of kir6.2 using Errat2. The overall quality factor for the second and third models deposited in the Protein Model Portal was computed to be 69.132 (Supplementary Fig. 3B) and 67.508 (Supplementary Fig. 3C), respectively, which is quite poor in comparison to the quality score of 78.778 (Supplementary Fig. 3A) computed for the current model of kir6.2 (PM0079770). Again, superimposition of the second model (blue color) available in Protein Model Portal and the present model of kir6.2 (red color) also gives a clear-cut idea of the quality of the model presented here (Supplementary Fig. 4). The quality of the backbone folding pattern of the present model (Supplementary Fig. 5A) in comparison to the third model available in Protein Model Portal (Supplementary Fig. 5B) is also good. From the above, it is found that the model predicted here for kir6.2 is good in comparison to all three existing models available in Protein Model Portal.

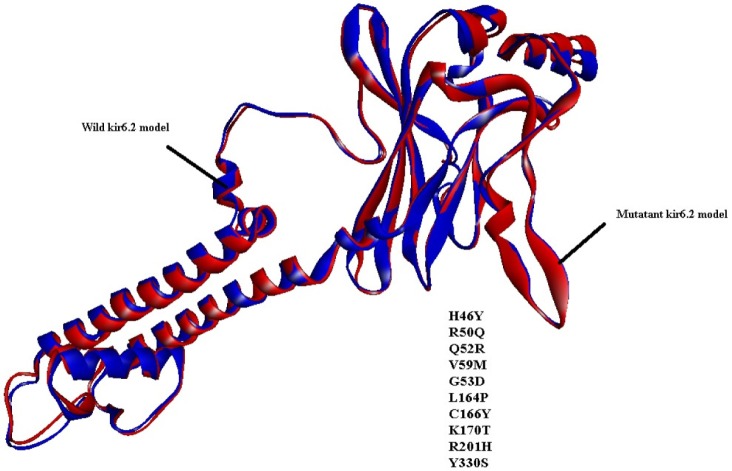

Structural comparison of wild and mutant models of kir6.2

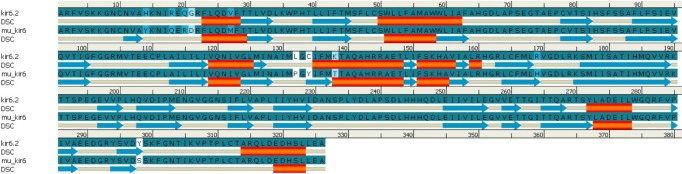

Similarly, by comparison of the wild and mutant models of kir6.2, the quality is confirmed as good for both predicted models of kir6.2, because the values of the computed z-score of the computed models of kir6.2 are within the range of z-scores of the groups of structures from different sources, like X-ray and nuclear magnetic resonance (Supplementary Fig. 6). The Ramachandran plot statistics (Supplementary Fig. 7) show 93.8% of residues in the most favored region in the case of the wild kir6.2 model, whereas in the mutant model, 92.8% of residues are found in the same region. At the same time, no residues were found in the disallowed region in both the wild and mutant models of kir6.2, which signified the good quality of the backbone folding pattern in both models. The non-bonded interactions between different atoms were plotted residue-wise against error function to calculate the overall quality factor of both models in Errat2, which justified the improvement in quality of kir6.2 mutant model (Supplementary Fig. 8). The comparison of secondary structural elements of both wild-type and mutant kir6.2 (Supplementary Table 1) reveals that there is an increment in disordered regions in the mutant model, but there is no major structural deviation due to the mutation introduced at the sequence level (Fig. 1). This is also supported by the root mean square deviation of the main chain at the tertiary structural level, which is computed as 0.854 by superimposition of the structural models of both wild and mutant kir6.2 (Fig. 2).

Comparison of predicted secondary structures in wild-type (kir6.2) and mutant-type (mu_kir6.2) model. Alignment done for amino acids 33-358 of kir6.2 models. Secondary structural element (DSC) helix is represented by red cylinder, and beta sheets are represented by blue arrows in the picture.

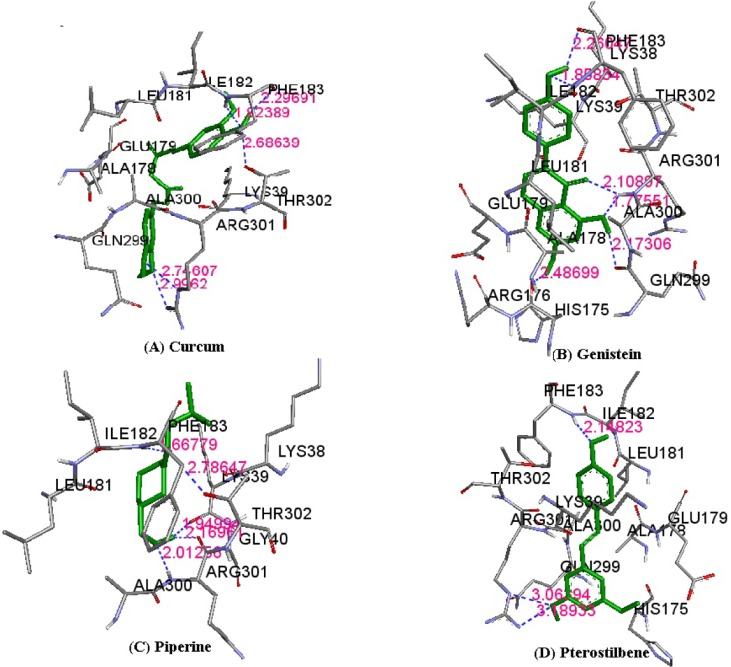

Molecular docking analysis of kir6.2 model with phytochemicals

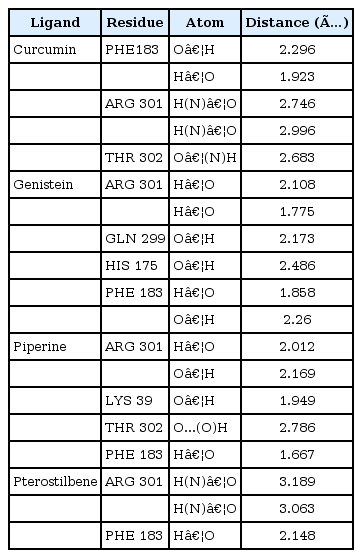

The results of molecular docking between the wild-type kir6.2 model and all four phytochemicals (Supplementary Fig. 1) separately for 100 runs (blind docking) and 10 runs (ATP-binding site docking) revealed that phytochemicals bind favorably in the same pocket of the wild kir6.2 model. The same observation was found in the case of the docking of the mutant kir6.2 model with the same phytochemicals (Supplementary Fig. 1), which supports the prediction of the pocket as an active binding region for phytochemicals. The best docked poses found in energetically favorable binding conditions with phytochemicals are reported (Supplementary Table 2). The comparative data of interacting residues within 4 Å in both the wild and mutant kir6.2 predicted models are reported in Table 1. The hydrophobic amino acids Ala-178, Leu-181, Phe-183, and Ala-300 are found within the pocket, providing stability towards the binding of phytochemicals with the kir6.2 models. The interacting residues of the mutant kir6.2 model are deciphered in Fig. 3, along with hydrogen bond interactions within 3.5 Å of distance (Table 2). As per the information in Table 2, the amino acids Phe-183 and Arg-301 have common involvement in hydrogen bonding in the mutant model of the kir6.2 protein with curcumin, genistein, piperine, and pterostilbene, suggesting strong binding affinity in the predicted binding pocket.

Hydrophobic amino acid residues of kir6.2 models (wild-type and mutant) participating in binding interaction within 4 Å within the binding pocket with phytochemicals

Atomic interaction shown between phytochemicals curcumin (A), genistein (B), piperine (C), and pterostilbene (D) with mutant kir6.2 model within the binding pocket. Hydrogen bond interactions within 3.5 Å are presented in dotted lines in the pictures.

Discussion

It is a well-established fact that the main cause of type 1 diabetes is the autoimmune destruction of β-cells in the pancreas [1]. Reports demonstrate that kir6.2 is an ATP/ADP ratio-sensitive protein that plays a vital role in operating the K+ channel and simultaneously controls Ca+2 ion channel function, which in turn triggers the exocytosis of insulin. But, due to mutations [10] in certain amino acids (H46Y, R50Q, Q52R, G53D, V59M, L164P, C166T, K170T, R201H, and Y330S), the whole mechanism is perturbed, blocking the exocytosis of insulin, which might be a cause of type-1 diabetes. Again, due to the unavailability of the crystal structure of kir6.2, molecular targeting with drugs is difficult. But, a rational design of in silico structure prediction approaches comes in handy under such circumstances to study this further. From the structural inspection of both wild-type and mutant kir6.2 models, it is concluded that mutation has no major structural changes or deviation in the structure quality of the model. In recent years, due to the adverse effect of synthetic drugs, phytochemicals have drawn substantial attention as alternative medications. The literature reports curcumin, genistein, piperine, and pterostilbene to have strong inhibitory effects against type 1 diabetes. Hence, all four of these phytochemicals were docked with predicted models of kir6.2 in the ATP-binding pocket [12] to check the inhibitory effect after mutation. The results of docking suggested that all phytochemicals bind at high affinity with both models, and the common interacting residues Ala-178, Leu-181, Phe-183, and Ala-300 were found in the same pocket, even after mutation. Amino acid residues, like Phe-183 and Arg-301, have also been observed as participating in hydrogen bonding within the binding pocket of mutant kir6.2 in the case of docking with all four inhibitors, supporting the fact that mutation might not affect the binding affinity of kir6.2 protein with phytochemicals. The current investigation concluded that phytochemicals, like curcumin, genistein, piperine, and pterostilbene, have strong inhibitory effects on kir6.2 protein. In addition, the study reports that these four phytochemicals namely, curcumin, genistein, piperine, and pterostilbene are effective in both normal and mutant conditions of kir6.2, suggesting future implications for type 1 diabetes mellitus treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Department of Biotechnology, Govt. of India, for providing the BIF Centre facility to carry out the current research work. Also, the authors are grateful to the authorities of the Department of Bioinformatics, Centre for Post Graduate Studies, Orissa University of agriculture & Technology, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, for their constant encouragement and allowing this research work to be accomplished.

References

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including two tables and eight figures can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-12-283-s001.pdf.

Supplementary Table 1

Comparison of secondary structural elements resulting from Phyre2 server for kir6.2 models

Supplementary Table 2

Binding energy and inhibition constant of best poses of phytochemicals docked within the binding pocket of wild-type and mutant kir6.2 models

Suppementary Fig. 1

Phytochemicals extracted from Pubchem database showing antidiabetic property

Supplementary Fig. 2

The Z-score are plotted for kir6.2 current model (A), second existing model of kir6.2 models (B), and third existing model of kir6.2 (C) indicate overall model quality. The black dot spot in the picture specifies the current predicted kir6.2 model is in the range of Z-scores of all experimentally determined protein chains in current PDB.

Supplementary Fig. 3

The overall quality of non-bonded interactions between atoms of current model of kir6.2 (A), second existing kir6.2 model (B), and third existing kir6.2 model (C) are depicted residue wise along X-axis with respect to error function along Y-axis. Two lines drawn on error axis to indicate the confidence percentage with which it is possible to reject regions that exceed that error value.

Supplementary Fig. 4

Super imposition of predicted model of kir6.2 wild type (red color) and second existing model of kir6.2 (blue color).

Supplementary Fig. 5

The backbone folding patterns plotted for current kir6.2 model (A) and third existing model of kir6.2 (B). Each black dot spot corresponds to one amino acid residue of kir6.2 chain. On the plot most favoured regions, additional allowed regions, generously allowed regions and disallowed regions are shown in red, yellow, light yellow and white color respectively.

Supplementary Fig. 6

The z-score are plotted for wild type kir6.2 (A) and mutant type kir6.2 (B) models indicate overall model quality. The black dot spot in the picture specifies the kir6.2 model is in the range of z-scores of all experimentally determined protein chains in current PDB.

Supplementary Fig. 7

The backbone folding patterns plotted for wild type kir6.2 (A) and mutant type kir6.2 (B) models. Each black dot spot corresponds to one amino acid residue of kir6.2 chain. On the plot most favoured regions, additional allowed regions, generously allowed regions and disallowed regions are shown in red, yellow, light yellow and white color respectively.

Supplementary Fig. 8

The overall quality of non-bonded interactions between atoms of wild type kir6.2 (A) and mutant kir6.2 (B) models are depicted residue wise along X-axis with respect to error function along Y-axis. Two lines drawn on error axis to indicate the confidence percentage with which it is possible to reject regions that exceed that error value.