Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Candidate Loci Associated with Platelet Count in Koreans

Article information

Abstract

Platelets are derived from the fragments that are formed from the cytoplasm of bone marrow megakaryocytes-small irregularly shaped anuclear cells. Platelets respond to vascular damage, contracts blood vessels, and attaches to the damaged region, thereby stopping bleeding, together with the action of blood coagulation factors. Platelet activation is known to affect genes associated with vascular risk factors, as well as with arteriosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Here, we performed a genome-wide association study with 352,228 single-nucleotide polymorphisms typed in 8,842 subjects of the Korea Association Resource (KARE) project and replicated the results in 7,861 subjects from an independent population. We identified genetic associations between platelet count and common variants nearby chromosome 4p16.1 (p = 1.46 × 10-10, in the KIAA0232 gene), 6p21 (p = 1.36 × 10-7, in the BAK1 gene), and 12q24.12 (p = 1.11 × 10-15, in the SH2B3 gene). Our results illustrate the value of large-scale discovery and a focus for several novel research avenues.

Introduction

Blood circulates through the body, affecting the tissues by delivering oxygen and nutrients responsible for tissue viability. The size, number, and concentration of a cell in the blood vary among populations, and these have been regarded as factors influencing various disorders, such as erythrocytosis, anemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases. During the last 2 decades, genetic studies have revealed that there exists a genetic effect on several hematologic variables. Moreover, previous studies reported that genetic factors strongly influence the variation in the counts and size of blood cells [1, 2]. Although a few genes are known to affect hematologic traits, the physiological mechanisms underlying the traits are largely unrevealed.

Platelets are anuclear cytoplasmic fragments that play a key role in maintaining primary adhesion, aggregation, and secretion and providing procoagulant surface and clot retraction. The primary functions of a platelet count are to assist in the diagnosis of bleeding disorders and to monitor patients who are being treated for any disease involving bone marrow failure. Low platelet counts or abnormally shaped platelets are associated with bleeding disorders, whereas high platelet counts sometimes indicate disorders of the bone marrow. Platelet activation is known to affect genes associated with vascular risk factors, as well as with arteriosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Platelet count is a readily available laboratory test and has been associated with different clinical and epidemiologic factors and are tightly regulated and inversely correlated in the healthy population [3]. Furthermore, because platelet count differs between inter-ethnic groups, gender and ethnicity should be important considerations for a platelet count study [4].

Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) for hematological traits have been reported [5, 6, 7]. Particularly, 68 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with platelet count were identified by a GWAS [8]. However, although the heritability of variation in platelet count ranged from 54% to more than 80% [9, 10, 11], the genetic variants reported to date explain only a small fraction of the heritability in platelet count [12]. Therefore, new studies have opportunities to unveil additional genetic variants for explaining missing heritability [12].

In this study, we conducted a GWAS to find a contribution of the genetic basis on hematologic variables, such as platelet count, in Koreans.

Methods

Subjects

We conducted a GWAS using individuals sampled from a part of the Korean Genome Epidemiology Study (KoGES). The study subjects were recruited from population-based cohorts in the regions of Anseong and Ansan. The standardized examinations applied in this survey included 10,038 participants aged 40 to 69 years. Subjects for the replication study were recruited from the Health2 cohorts, another population-based cohort comprising the Wonju, Pyeongchang, Gangneung, Geumsan, and Naju regions in Korea. Among a total of 8,500 participants within the Health2 cohort, 7,861 subjects were selected for the replication analysis based on their age and information about concomitant disease and medication [13].

Platelet counts and genotyping

Peripheral blood was isolated by using the G-DEX TM IIb DNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea). Platelet count was measured using an ADVIA 120 (Bayer, Tarrytown, NY, USA). Genomic DNA, genotyped on the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP array 5.0 (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), was isolated from peripheral blood drawn from Anseong and Ansan cohort participants. Of 9,603 genotyped samples, we excluded samples with high heterozygosity (>30%, n = 11) and gender inconsistencies (n = 41). Also, individuals who had developed any kind of cancer (n = 101) were excluded from subsequent analyses. To examine population stratification overall, related or identical individuals with higher values than first-degree relatives of Korean sib-pair samples were also excluded according to average pair-wise identity-by-state (IBS) values (>0.80, n = 608). The methods to estimate heterozygosity and IBS have been described elsewhere [13]. SNP markers with a high missing genotype rate (>5%), low minor allele frequency (MAF, <0.01), and significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 1 × 10-6) were excluded. Consequently, a total of 352,228 markers were used for the GWAS. For the replication analysis, 19 SNPs of the Health2 population, comprising 7,861 participants, were genotyped by GoldenGate assay (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Imputation

Imputation was carried out by using the IMPUTE program version 1 (http://mathgen.stats.ox.ac.uk/impute/impute.html) [14, 15]. On the basis of NCBI, build 36 and dbSNP, build 126, we initially used 90 individuals from Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT) and Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB) founders in HapMap as a reference panel, comprising 3.99 million SNPs (release 22). After removing SNPs with an MAF < 0.01 and an SNP missing rate > 0.05, we combined the remaining 1.8 million imputed SNPs with the directly typed Korea Association Resource (KARE) SNPs for the association analyses. Association analyses for imputed SNPs were carried out by the SNPTEST program (http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~marchini/software/gwas/snptest.html).

Statistical analysis

Association analysis of platelet trait with genotypes was performed using a linear regression model, adjusting for age, sex, and recruitment area. Analyses were performed with the software PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink), SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and R statistics package version 2.7.1. The KARE GWAS and replication study were combined by an inverse-variance meta-analysis method, assuming fixed effects, with Cochran's Q test to assess between-study heterogeneity [16]. Regional plots were generated using LocusZoom [17].

Results

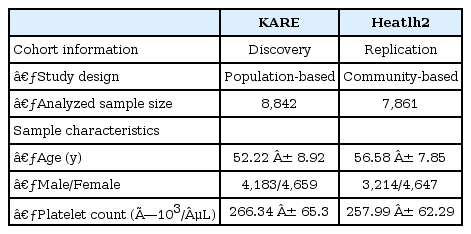

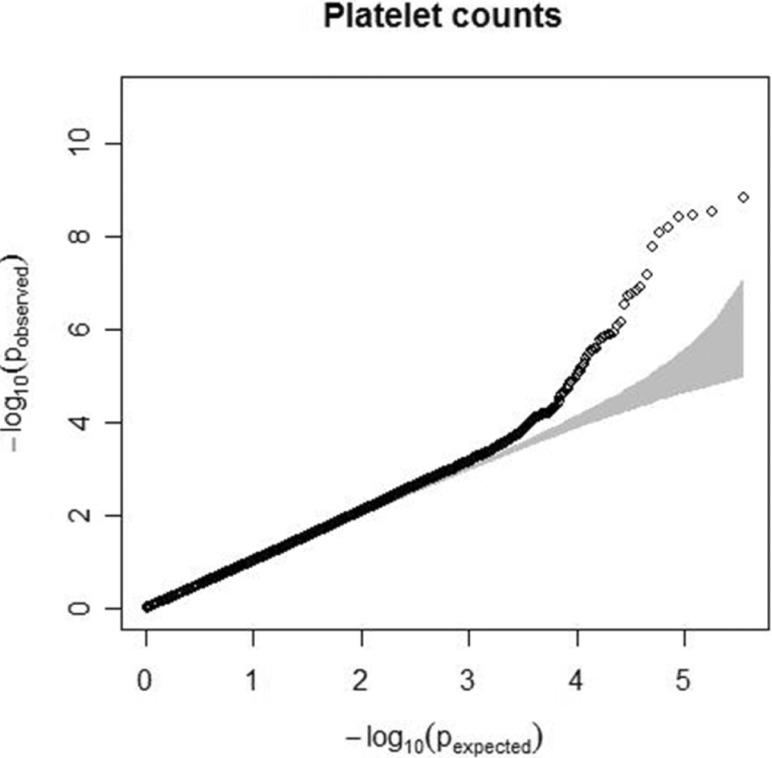

Characteristics of the study participants, including age, sex, and trait summaries, are presented in Table 1. Quantile-quantile analysis of 2-d.f. logistic regression statistics for the comparison of genotype frequencies in the cohorts confirmed the genetic homogeneity of these two components of the KARE study population (Fig. 1). We observed significant SNPs by applying a Bonferroni adjustment cut-off with a combined p-value < 1.0 × 10-7. The GWAS identified several genomic locations as potentially associated with platelet count (Fig. 2). In a follow-up examination of the Health2 cohort, we examined 7,861 selected from 8,500 participants (aged, 40 to 69 years). We confirmed 3 replicated signals, of which 3 signals, replicating previously documented reports, and one novel locus were discovered.

Quantile-quantile plot for platelet count. The observed p-values (y axis) were compared with the expected p-values under the null distribution (x axis) for each trait. The shaded region represents the 95% concentration band.

Chromosome plot for platelet counts. Genome-wide association study for log-transformed platelet count on a population-based sample of 8,842 individuals from the Korea Association Resource (KARE) study. The x axis represents the genomic position (in Gb) of 352,225 single nucleotide polymorphisms; they show -log10(p-value). Single nucleotide polymorphisms with a p-value < 1 × 10-4 are highlighted in red.

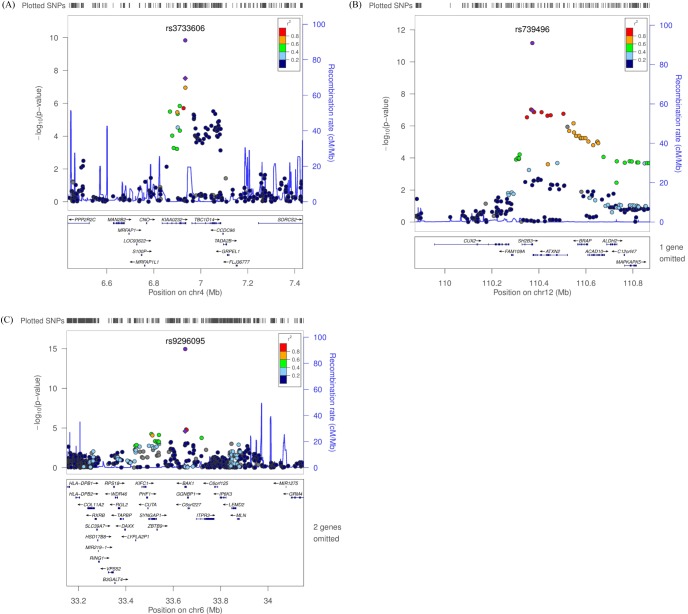

We observed 3 independent signals with p < 10-5 for platelet counts. Table 2 and Fig. 3 show results for three regions that had combined genomewide significant evidence for association with platelet count in the KARE GWAS and replication samples. For platelet counts, the strongest evidence for association was at 12q24 (rs739496, MAF = 0.11, combined p = 1.15 × 10-15) (Table 2, Fig. 3B). The associated signal is concordant with a previously published result in the Japanese population [6]. This SNP is located in the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of SH2B adaptor protein 3 (also known as LNK). SH2B3 is a member of the APS family of adaptor proteins, which play a pivotal role as broad inhibitors of growth factors and cytokine signaling pathways. The second SNP, rs3733606 (MAF = 0.50, combined p = 1.46 × 10-10) (Table 2, Fig. 3A) in 4p16, is in the 3' UTR of the KIAA0232 gene, which translates the functionally unknown hypothetical protein LOC9778. The third locus associated with platelet is at 6p21 (rs9296095, MAF = 0.23, combined p = 1.67 × 10-7) (Table 2, Fig. 3C).

Regional plot of three discovered variants. (A-C) p-value plots showing the association signals in the region of KIAA0232 on chromosome 4 (A), SH2B3 on chromosome 12 (B), and BAK1 on chromosome 6 (C). In the top panel, the association signals scaled by -log10(p-value) (typed or imputed SNPs) at each locus are distributed in a genomic region 500 kb to either side of the lead association signal (typed). Each SNP is plotted as a circle along the chromosomal position, and linkage disequilibrium between the lead SNP and the other SNPs is colored as a scale from low (blue) to high (red) or is colored gray if linkage disequilibrium information was not available in the 1,000 genomes June 2010 CHB+JPT samples. The lead SNP is colored purple diamond, and the overall meta-analysis result is shown with a purple circle. The recombination rate estimated from HapMap phase 2 is plotted in blue. The bottom panel illustrates the locations of known genes. Genetic information is based on NCBI build 36 and dbSNP build 130. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; CHB, Han Chinese in Beijing, China; JPT, Japanese in Tokyo, Japan.

Discussion

We performed a GWAS of platelet count using 352,225 SNPs profiled with the Affymetrix Genome-Wide human SNP array 5.0 in 8,842 individuals from the Anseong and Ansan cohorts as described previously [13]. In a two-stage design (8,842 discovery and 7,861 replication samples), we confirmed three loci associated with platelet count at a genomewide significance level (< 1.0 × 10-7). Besides an unknown functional gene, we found two candidate genes, SH2B3 and BAK1, responsible for the variation in platelet counts. These genes are potential candidates for affecting platelet count.

Lymphocyte adapter protein (SH2B3, also known as LNK) is expressed in hematopoietic precursor cells and in endothelial cells and is known to be involved in inflammation [18]. LNK-deficient mice show a marked difference of hematopoiesis, accompanying increased numbers of various types of cells, such as megakaryocytes, B lymphoid, erythroid progenitor, and hematopoietic stem cells [19]. Several SNPs within the SH2B3 region are well known as variants associated with blood pressure, myocardial infarction, type 1 diabetes, and celiac disease [20].

BAK1, a multidomain pro-apoptotic family member, has shown to be involved in apoptotic cell death, playing a role as an essential mediator [21, 22, 23, 24]. Kamatani et al. [6] reported that BAK1 is a putative strong candidate gene accounting for numbers of platelets. This SNP is located in the 4th intron in BAK1 (Bcl2-antagonist/killer1), which encodes a protein acting as a strong proapoptotic effector that is known to control platelet lifespan [25]. The intrinsic machinery for apoptosis regulates the life span of anucleate platelets [25].

KIAA0232 has no known biological function and no clue for a related biological pathway. Given the weak linkage disequilibrium block around KIAA0232, further investigation is required for the biological function.

Some studies have discovered genetic factors associated with platelet count through genome-wide associated studies across diverse ethnic groups [12, 26]. Qayyum et al. [12] reported that a candidate gene, BAK1, was significant in African-Americans. Also, Shameer et al. [26] reported that SH2B3 and KIAA0232 in European ancestry were also significant in platelet count and mean platelet volume, respectively.

Numerous previous studies have demonstrated the association between platelet counts and various phenotypes in human and mice [27]. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Community (ARIC) study has shown that platelet counts are positively correlated with leukocytes [28]. Turakhia et al. [29] also reported the association between higher platelet counts and residual thrombus after fibrinolytic therapy, which is in agreement with the ARIC study. The evidence of a relationship between platelet count and insulin resistance in non-obese type 2 diabetic patients was reported from a study on Japanese [30]. The number of platelets is also a possible predictor of the risk of death and cardiovascular disease [31].

In conclusion, we identified and validated common variants at 1 novel locus, BAK1, and 2 known variants, SH2B and KIAA0232, responsible for the variation of platelet counts in population-based cohorts. Our research demonstrates the results from a meta-analysis and follow-up genotyping to retrieve positive evidence for the association of 3 loci with platelet counts. In addition, fine mapping and functional studies on the discovered loci will help us understand the hidden physiological mechanisms underlying platelet count.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (4845-301) and an intramural grant from the Korea National Institute of Health (2012-N73002-00).

Notes

This is 2014 KOGO best paper awarded.