Introduction

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is a common monogenetic disorder, affecting as many as 1 in 500 people in the general population. The disease is characterized by the formation of multiple fluid-filled renal cysts that expand over time and destroy the architecture of the kidney. Five percent of all cases of chronic renal failure are due to ADPKD, and approximately 50% of ADPKD patients will develop end-stage renal disease by the time they are 60 years of age [1].

In the early stages of ADPKD, numerous cysts begin to enlarge from many segments of the kidney. Later, the enlarged regions disassociate from the original nephron to form the actual cysts, which continue to enlarge due to proliferation of epithelial cells and fluid secretion into the cyst lumen. Progressive renal cyst formation and enlargement result in a loss of renal function and hypertension and culminate in renal failure. It is generally believed that cysts enlarge by means of abnormal cell growth, forming what is essentially a fluid-filled tumor that fills by transepithelial fluid secretion. Cyst enlargement may then lead to extracellular matrix remodeling, interstitial fibrosis, a general inflammatory response, and disruption of the normal renal parenchyma, which then interfere with glomerular filtration and vascular blood flow, giving rise to cell death by apoptosis and ultimately renal failure [2].

Many studies have indicated that most cases of ADPKD are accounted for by mutations in the PKD1 and PKD2 genes, encoding the transmembrane protein polycystin-1 (PC1) and polycystin-2 (PC2), respectively. Mice with targeted mutations in the PKD1 or PKD2 genes develop cystic kidneys during embryogenesis, and ADPKD in humans is associated with mutations in the PKD1 or PKD2 genes [3, 4]. In addition, the product of the PKD1 gene, PC1, has been implicated in a variety of pathways tied to proliferation, including G-protein signaling and the Wnt, activator protein 1 (AP-1), and Janus kinase-signal transducers and activators of transcription cascades [5, 6]. Moreover, depletion of PC1 has been shown to increase cell growth, whereas its overexpression slows cell growth, indicating that PC1 may negatively regulate cell proliferation [7, 8]. PC2, the protein product of PKD2, has also been implicated in cell cycle regulation via its calcium channel activity and stimulation of AP-1 [9, 10]; however, there has been little direct evidence tying PC2 to this process.

Here, we created a number of related cell lines that varied in their expression of PC2. We describe studies designed to identify target genes under the control of the PKD2 using Pkd2 knockout (KO) and PKD2 transgenic (TG) mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs). We used a mouse 30 K whole gene oligonucleotide microarray to identify messenger RNAs whose expression was altered by the overexpression of the PKD2 or KO of the Pkd2 in MEF cells.

Methods

Establishment of MEF derived from wild-type and PKD2 mutation embryos

MEF were acquired from PKD2 TG embryos or Pkd2 KO embryos during development (13.5 days) [11]. Heads and limes were removed from embryos. The remaining embryonic tissues were minced and dispersed in 0.05% trypsin prior to incubation at 37℃ for 15 min. Cells were plated in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium of Defined Minimal Essential medium (Welgene Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Welgene Biotech) and were cultured at 37℃ in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 until confluent growth was achieved. MEF cells were frozen as stocks at the second passage and were used for the subsequent studies at the third passage.

Microrray hybridization and data analysis

Total RNA was prepared using a commercial kit (Qiagen, Valancia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Gene expression profiles were obtained using the CodeLink Uniset Mouse Expression Bioarray (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). The 30,000 gene probes contained in the bioarray allows the detection of differences in gene expression as low as 1.3-fold with 95% confidence. Ten micrograms of total RNA was amplified, and labeled cDNA was produced. Biotin-labeled cDNA was hybridized to the array overnight in a shaking incubator at 37℃, and excess target sequences were washed away using a series of saline sodium citrate washes. The array was stained by treatment with streptavidin-Alexaflour 647 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), the excess was washed away, and the array was scanned at an excitation wavelength of 632 nm using a GenePix scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The resulting image was quantified, and the intensity of each spot was divided by the median spot intensity to provide a scaled and comparable number across multiple arrays.

DNA microarray scanning and analysis

Microarrays were scanned using an Arraywox scanner (Applied Precision, Seattle, WA, USA), analyzed using ImaGene version 5.1 software (Biodiscovery, Segundo, CA, USA), and normalized using Genesight version 3.2 software (Biodiscovery). Normalization was performed by subtracting the means of all genes. The data normalized by Genesight were compared using an M/A plot. Genes differentially expressed were identified by intensity differences, after subtracting the background intensity. Genes showing expression changes of at least 2-fold were selected, and these selected genes were clustered by the hierarchical method.

Clustering algorithm

The normalized log ratio corresponding to each time point was exported to the software for clustering algorithm. Acuity version 3.1 (Molecular Devices) was used for the 'gene shaving' algorithm. To estimate the number of clusters in a dataset, the 'Gap Statistics' attribute of the Acuity software package was used. The cluster number, estimated by gap statistics, was used for an input parameter in gene shaving. After gene shaving, a single linkage was used for hierarchical clustering.

Semi-quantitative and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared using a commercial kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Single-strand cDNA was synthesized by incubating 5 µg total RNA with 200 units AMV, 100 nM oligo(dT)12-18, 1 mM dNTP mixture, and 40 units RNase inhibitor at 42℃ for 1 h in a final volume of 25 µL. The reaction was terminated by incubation at 70℃ for 15 min. The initial amount of mRNA and reaction conditions were optimized to obtain linearity for mouse 18s rRNA. For semi-quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, the used primers were: human PKD2, forward 5'-CGTGCCCCAGCCCAGTC-3' and reverse 5'-TTCCAGTACAGCCCATCCAATAAG-3'; mouse Pkd2, forward 5'-TGCGAGGGCTGCGAGGTC-3' and reverse 5'-TGTCAGCTTGCGTGTGGTTGC-3'; mouse 18s rRNA, forward 5'-GTAACCCGTTGCACCCCATT-3' and reverse 5'-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3'. RT-PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95℃, 25 cycles of 50 s at 94℃, 50 s at 57℃, 50 s at 72℃, and 5 min at 72℃. The amplified products were separated on a 1% agarose gel. For real-time PCR, the used primers were: mouse β-actin, (forward 5'-GACGATGCTCCCCGGGCTGTATTC-3' and reverse 5'-TCTCTTGCTCTGGGCCTCGTCACC-3') used as a positive control; mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ), forward 5'-TCTTAACTGCCGGATCCACAAAAA-3' and reverse 5'-ATCTCCGCCAACAGCTTCTCCTTC-3'; mouse protein kinase α (PKCα), forward 5'-GGGCAGCCTCCGTTTGATGGT-3' and reverse 5'-CGCTTGGCAGGGTGTTTGGTC-3'; mouse Wnt4, forward 5'-GCCATCGAGGAGTGCCAATACC-3' and reverse 5'-GGCCACACCTGCTGAAGAGATG-3'; mouse integrin α4 (ITGα4), forward 5'-GTAGCCCCAGTGGAGAGCCTTGTG-3' and reverse 5'-ATGCCAGTGGGGAGTTTGTTATCG-3'; mouse IL6ST, forward 5'-TGAATCGGACCCACTTGAGAGG-3' and reverse 5'-CAGGAGCGGCTTGTTTGAGGTA-3'; mouse aquaporin 1 (AQP1), forward 5'-GGAGGCGCCGAGACTTAGGT-3' and reverse 5'-GCGGGTGAGCACAGCAGAGC-3'; mouse transforming growth factor-β2 (TGF-β2), forward 5'-TCATCCCGAATAAAAGCGAAGAGC-3' and reverse 5'-AGGGCAACAACATTAGCAGGAGAT-3'. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using the real-time SensiMixPlus SYBR kit as described by the manufacturer's instructions (Quantance, London, UK).

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted using radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer in MEF cells. Proteins were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacryamide gel electrophoresis and were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Bellerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and were incubated with various antibodies. Antibodies to PC2 (anti-human and anti-mouse) and AQP1 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies to β-actin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-Wnt4 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Each membrane was washed with phosphate-buffered saline-Tween, and immunocomplexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

Results

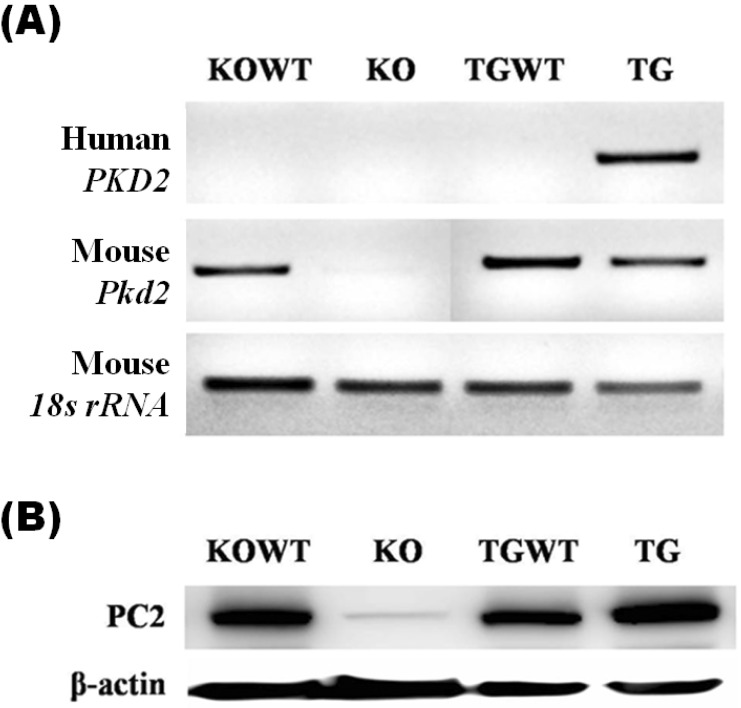

Confirmation of PKD2 expression in Pkd2 KO and PKD2 TG MEFs

Mouse Pkd2 mRNA was revealed in KO wild-type (KOWT) MEF cells but not in KO MEF cells. Also, Pkd2 mRNA was expressed in TG wild-type (TGWT) MEF cells and PKD2 TG MEF cells. Human PKD2 mRNA was only expressed in PKD2 TG MEF cells obtained from PKD2 TG embryos following injection of the human PKD2 transgene (Fig. 1A). Consistently, the expression level of polycystin-2 was lower in KO MEFs than KOWT MEFs as well as higher in TG MEFs than TGWT MEFs (Fig. 1B).

Microarray gene expression analysis

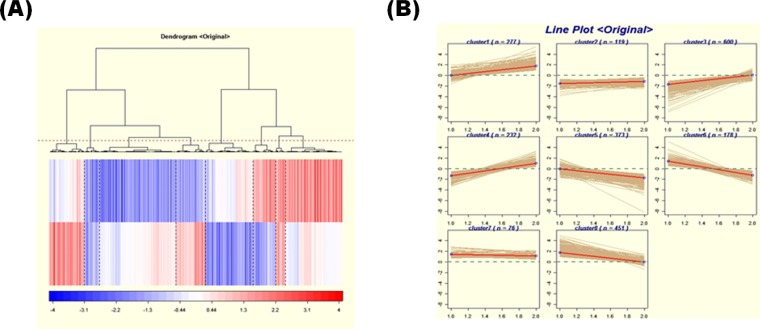

We used a mouse 30 K whole gene oligonucleotide microarray to identify mRNAs whose expression was altered by the Pkd2 KO and PKD2 TG MEF cells. The normalized log ratios corresponding to each time point were exported to the software for clustering algorithm. We used Axon's Acuity 3.1 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) for using the 'gene shaving' algorithm. To estimate the number of clusters in a dataset, we used 'Gap Statistics' in Acuity 3.1. The cluster number estimated by gap statistics was used for an input parameter in gene shaving. After gene shaving, we used a single linkage hierarchical clustering. The single linkage hierarchical clustering method divides 8 'gene shaving' clusters (Fig. 2). The majority of genes whose expression was appreciably altered encoded proteins involved in critical biological processes, such as metabolism, transcription, cell adhesion, cell cycle, and signal transcription. Forty-five genes whose expression was changed by 2-fold or greater were identified (Table 1).

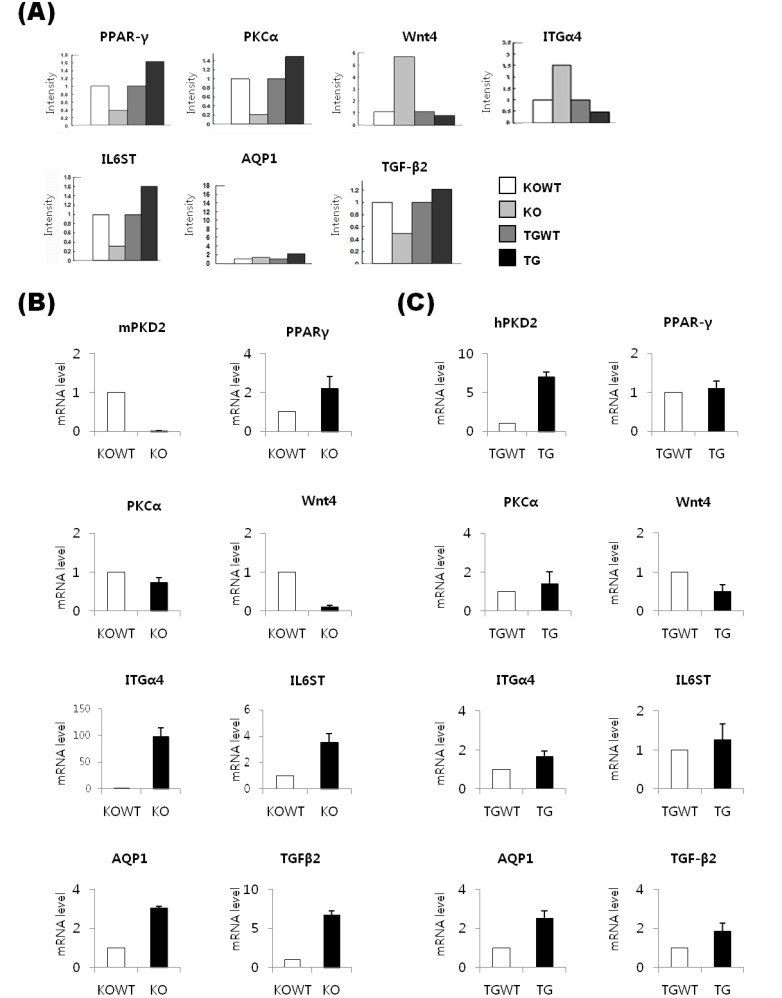

Verification of candidate genes by quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblot analysis

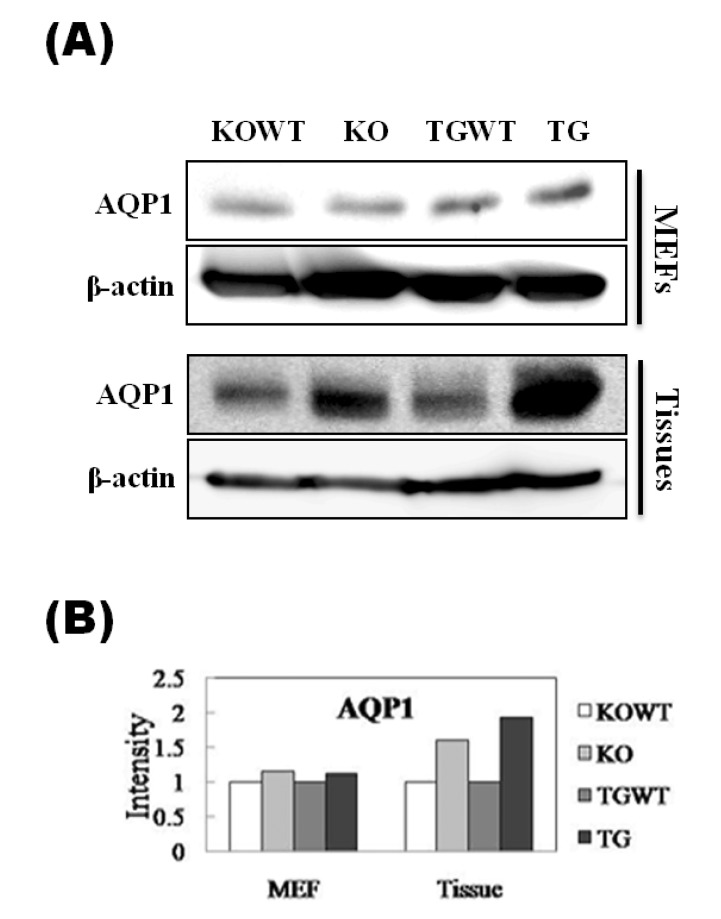

To verify the results obtained by cDNA microarray analysis, expression patterns for selected genes were confirmed at the RNA and protein levels. We selected seven genes among the 45 genes (Fig. 3A). As result of realtime RT-PCR, the expression patterns of PKCα, ITGα4, and AQP1 were identical to microarray analysis in Pkd2 KO MEF cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast, 6 genes, except for TGF-β2, were identically expressed in PKD2 TG MEF cells (Fig. 3C). Especially, the AQP1 gene may be significantly regulated by differential Pkd2 gene expression level. Furthermore, to confirm the AQP1 protein expression level, western blot analysis was performed using MEF cells as well as kidney tissues obtained from Pkd2 KO (or heterozygote) and PKD2 TG mice. As result, AQP1 protein level was consistent with mRNA levels in both MEFs and tissues (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Although remarkable progress toward understanding the genetics and pathophysiology of ADPKD has been made to date, it is still unclear how mutations in disease-causing genes trigger cystogenesis and what important role other molecules play in the cystic phenotype [12]. Our aim here was to identify genes associated with the cystic phenotype using Pkd2 KO and PKD2 TG MEF cells. In a previous study, overexpression of human PKD2 led to anomalies in tubular function, due to abnormalities in tubule morphogenesis [13]. Similar findings have been made for the PKD1 gene. For this gene, gain/loss of function and haploinsufficiency leads to cystogenesis, with the severity of the phenotype being related to the level of imbalance. More severe phenotypes are seen for gain and loss of function than for haploinsufficiency [4]. In the present study, the association between cystogenesis and the loss or gain of PKD2 supports the idea that PC2 functions through Pkd2 mutant MEF cells.

Presently, we found Wnt4 to be up-regulated in Pkd2 KO MEF cells and down-regulated in PKD2 TG MEF cells. Wnt4, a member of the Wnt family of lipid-modified secreted glycoproteins, plays central roles in the initial stages of the tubulogenic program. Wnt4 is expressed in the pretubular aggregate, as one of the first molecular responses to inductive signaling mediated by ureteric epithelium [14].

AQP1 was observed to be up-regulated in both Pkd2 KO and PKD2 TG MEF cells. AQP1 is a channel-forming integral membrane protein found in erythrocytes and water-transporting tissues, including the kidney, where it is localized to the proximal tubules and thin descending limbs of Henle's loop. The selective expression pattern of AQP1 in human nephrogenesis suggests that proximal tubules and thin descending limbs become permeable to water early in development. A predominantly apical expression of AQP1 is found during a critical period of the nephrogenesis, during formation of the proximal tubule, as well as in the early stage of ADPKD; in normal tubules, distribution is both apical and basolateral [15]. Another interesting defect in urine-concentrating ability was described in the Aqp1 knockout mouse. Although these mice were grossly normal in terms of survival and appearance, they were vulnerable to water deprivation and became severely dehydrated. These results suggest that AQP1 is required for the formation of concentrated urine [16].

We have found PKC-α and Bcl-2 associated transcription factor to be down-regulated in Pkd2 KO MEF cells and up-regulated in PKD2 TG MEF cells. Recent observations in animal models of PKD have implicated apoptosis in its pathogenesis. PKC- and Erk-dependent pathways are critical components of the cell survival by suppressing the apoptosis [17]. We also have demonstrated the role for PKD2 in cellular adhesion processes. In this study, ITGα4 was up-regulated in Pkd2 KO MEF cells and down-regulated in PKD2 TG MEF cells. It suggests that adhesion molecule such as ITGα4 may be associated with PKD2 mutation-related pathogenesis.

In conclusion, by using the cDNA microarray technique, we have found several candidate genes that may be involved in cystogenesis: PKCα, ITGα4 and AQP1. These genes were affected by PKD2 expression and may be related to cyst formation of kidney together with the PKD2 gene.