Molecular Characterization of Legionellosis Drug Target Candidate Enzyme Phosphoglucosamine Mutase from Legionella pneumophila (strain Paris): An In Silico Approach

Article information

Abstract

The harshness of legionellosis differs from mild Pontiac fever to potentially fatal Legionnaire's disease. The increasing development of drug resistance against legionellosis has led to explore new novel drug targets. It has been found that phosphoglucosamine mutase, phosphomannomutase, and phosphoglyceromutase enzymes can be used as the most probable therapeutic drug targets through extensive data mining. Phosphoglucosamine mutase is involved in amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism. The purpose of this study was to predict the potential target of that specific drug. For this, the 3D structure of phosphoglucosamine mutase of Legionella pneumophila (strain Paris) was determined by means of homology modeling through Phyre2 and refined by ModRefiner. Then, the designed model was evaluated with a structure validation program, for instance, PROCHECK, ERRAT, Verify3D, and QMEAN, for further structural analysis. Secondary structural features were determined through self-optimized prediction method with alignment (SOPMA) and interacting networks by STRING. Consequently, we performed molecular docking studies. The analytical result of PROCHECK showed that 95.0% of the residues are in the most favored region, 4.50% are in the additional allowed region and 0.50% are in the generously allowed region of the Ramachandran plot. Verify3D graph value indicates a score of 0.71 and 89.791, 1.11 for ERRAT and QMEAN respectively. Arg419, Thr414, Ser412, and Thr9 were found to dock the substrate for the most favorable binding of S-mercaptocysteine. However, these findings from this current study will pave the way for further extensive investigation of this enzyme in wet lab experiments and in that way assist drug design against legionellosis.

Introduction

Legionella pneumophila is a gram-negative intracellular facultative pathogen that is mainly responsible behind hospital and community-acquired legionellosis and about 90% cases of legionellosis are caused by this species [1]. Legionellosis patients predominantly have pneumonia, chills, fever even their cough likely to be dry or phlegm nature. L. pneumophila isolation by comparing clinical and environmental L. pneumophila isolates precludes different sources whether it is contagious or not through a number of typing methods. Such methods of typing make it's easier like pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), is usually considered to be extremely biased [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. PFGE can recognize unique strains of L. pneumophila with a precise profile that is considered sporadic. The origin of L. pneumophila sg 1 clone was identified at 1997. In Paris, legionellosis was caused by a single L. pneumophila sero group 1 strain [7]. An ample of enzymes is required in bacterial metabolism. Drugs resistance against L. pneumophila considered to the search for most novel drugs of designing. At present, computational analysis was taken place in order to discover novel drug targets that are non-homologous to human. All enzymes involved in metabolic pathway of those certain bacteria are precursor to design such kind of drugs. Phosphoglucosaminemutase and phosphomannomutase, these two typically have the potential target sites. Phosphomannomutase is processed with glycosylation, adding the groups of sugar molecules (oligosaccharides) to proteins. The enzyme phosphoglucosamine mutase catalyzes the chemical reaction alpha-D-glucosamine 1-phosphate to D-glucosamine 6-phosphate, which converts alpha-D-glucosamine 1-phosphate to D-glucosamine 6-phosphate. This enzyme is phenomenally the same as phosphomannomutase, which transfers a phosphate group within a molecule. The systematic name of phosphoglucosamine mutase is alpha-D-glucosamine 1,6-phosphomutase. It participates in metabolism of amino sugars. Phosphoglucosamine mutase (GlmM) catalyzes the formation of glucosamine-1-phosphate from glucosamine-6-phosphate, an essential step in the pathway for UDPN-acetylglucosamine biosynthesis in bacteria. This enzyme must be phosphorylated to be active and acts according to a ping-pong mechanism involving glucosamine-1,6-diphosphate as an intermediate [8]. The phosphoglucosamine mutase auto-phosphorylates in vitro in the presence of ATP. The same is pragmatic with phosphoglucosamine mutases from other bacterial species, yeast N-acetylglucosamine-phosphate mutase, and rabbit muscle phosphoglucomutase. Labeling of GlmM enzyme with ATP requires divalent cation. The label can be lost if it is incubated more vigorously with of its substrates. At glycosylation, the phosphomannomutase enzyme converts mannose-6-phosphate to mannose-1-phosphate [9]. Mannose-1-phosphate is converted into GDP-mannose which transfers mannose to the growing oligosaccharides chain. Congenital disorder type Iais is initiated by mutations in the PMM2 gene. Mutations alter the formation of phosphomannomutase enzyme that lead to the reduced enzyme activity and shortage of GDP mannose within cells. As there have no enough activated mannose, incorrect oligosaccharides are produced. Abnormal glycosylated proteins in organs and tissues regulate the signs and symptoms in CDG-Ia [10]. In addition, it participates in the metabolism of both fructose and mannose.

So, homology modeling will predict the desired function and possible disease treatment if needed because of its importance on cell metabolism systems. The present study is aimed to predict the three-dimensional (3D) structure of phosphoglucosamine mutase by means of homology modeling. Consequently, to depict its structural features and to comprehend the molecular function, the structural model for the desired protein was constructed.

Methods

Sequence retrieval

The amino acid sequences of the enzyme phosphoglucosamine mutase in L. pneumophilia (strain Paris) were retrieved from the UniProt Knowledge Base (UniProtKB) database, which is the foremost hub for the compilation of well-designed information on proteins, with consistent, accurate, and rich annotation. The accession ID of phosphoglucosamine mutase is Q5X1A3, and it contains 455 amino acids.

Analysis of physico-chemical properties

ProtParam (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/), a tool of Expasy was used for the analysis of the physiological and chemical properties from the protein sequence. This tool can predict different physico-chemical properties, like the molecular weight, isoelectric pH, aliphatic index, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), and extinction coefficients.

Secondary structure prediction

Secondary structure was predicted by using the self-optimized prediction method with alignment (SOPMA) [11]. The protein's secondary structure includes an α helix, 310 helix, pi helix, beta bridge, extended strand, beta turns, bend region, random coil, ambiguous states, and other states. SOPMA predicts these properties by using homologous protein identification, sequence alignment, and conformational score determination method. Prediction accuracy was confirmed by correlation coefficient value. Plain text format data were inputted, and default parameters were set.

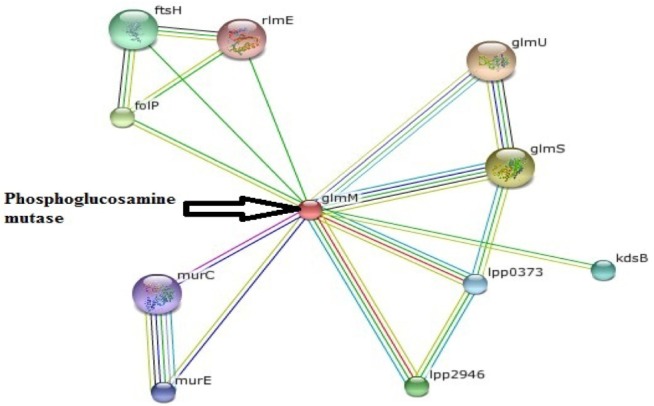

Protein-protein interaction networking

Protein cooperates with other proteins to perform accurate functions. To identify protein-protein interactions, STRING was used. STRING is a biological database that is used to construct protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks for different known and predicted interactions. At present, the database covers up to 5,214,234 proteins from 1,133 organisms [12].

Model building

3D structure determination of a protein is the key step of structural genomics initiative [13]. To predict the 3D homology model of phosphoglucosamine mutase, Phyre2 (Protein Homology/Analogy Recognition Engine) [14], the most popular online protein fold identification server, was used. Phyre2 uses a dataset of known proteins taken from different reliable databases, such as Structural Classification of Proteins (SCOP) database and Protein Data Bank (PDB). Through sequential steps, such as profile construction, similarity analysis, and structural properties, Phyre2 selects the best suited template and generates a protein model. To get an accurate model, intensive mode of protein modeling was selected. The input data of this enzyme were in FASTA format. In this respect, the intensive mode of protein modeling was selected in order to get an accurate model. After model building, it is necessary to further refine in quest of the best model generation.

Model refinement

Homology-based modeling often contains significant local distortions that render the structure models less useful for high-resolution functional analysis. To refine the predicted protein model, ModRefiner [15], an algorithm for atomic-level, high-resolution protein structure refinement, was used. Protein sequences were given in the FASTA format, and refinement was done for several times to get the most accurate structure.

Evaluation and validation of the model

The accuracy and stereo chemical quality of the predicted model were evaluated with PROCHECK [16, 17] by Ramachandran plot [18] analysis, which was done through "Protein structure and model assessment tools" of Swissmodel workspace; 2.5 Å resolution was selected for PROCHECK analysis. The best model was selected on the basis of overall G-factor, number of residues in the core, and allowed, generously allowed, and disallowed regions. ERRAT [19], Verify3D [20], and Qualitative Model Energy Analysis (QMEAN) [21] were used for further analysis of the selected model. The verified structure was visualized by Swiss-PDB Viewer [22].

Active site analysis

The active site is the specific region of the target protein responsible for its activity and is constructed of different amino acids. To identify the active site with the determined model, Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of proteins (CASTp) [23] server was used. This provides an online resource for locating, delineating, and measuring concave surface regions on three-dimensional structures of proteins, including pockets located on protein surfaces and voids buried in the interior of proteins.

Docking simulation study

Molecular docking is a computer simulation procedure to calculate the conformation of a receptor-ligand complex. It is used to identify the binding affinity and interaction energy of the molecules with the target protein. Docking analysis was performed by AutoDock Vina [24], which is an automated procedure for predicting the interaction of ligands with bio-macromolecular targets. Before initiating the docking stimulations, phosphoglucosamine mutase protein was modified by adding polar hydrogen, removing all the water molecules, and was also set with the grid box for its binding site, whereas all the torsional bonds of ligands were set free by the ligand module. To evaluate the binding energy on the macromolecule coordinate, a three-dimensional grid box (box size, 76 × 76 × 76 Å; box center, 11 × 90.5 × 57.5 for x, y, and z, respectively) was created using Auto Grid, which calculates the grid map. The combined binding with target protein phosphoglucosamine mutase and ligand, s-mercaptocysteine, was obtained by using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.5.0.4, Schrödinger, LLC) [25].

Results and Discussion

The UniProt Knowledge Base (UniProtKB) delivers an authoritative resource for protein sequences and functional information. Sequences of phosphoglucosamine mutase of Legionella pneumophilia (strain Paris) were obtained from UniProtKB. Manual annotation is the landmark of the SwissProt section of UniProtKB [26, 27]. The protein sequence was analyzed using the ProtParam server [28], which can predict the physical and chemical parameters for the protein. The parameters of this server are helpful for experimental handling of the protein, like biological analysis or extraction.

ProtParam results reveal that the protein has 23,295 extinction coefficients, 27.68 instability index, 108.00 aliphatic index, and 0.059 grand average of hydrophobicity, with more positively charged residues than negatively charged amino acids. The physico-chemical properties of phosphoglucosamine mutase are tabulated in Table 1.

Secondary structure analysis is increasing day by day to predict protein function and structure. The secondary structure of phosphoglucosamine mutase was predicted by SOPMA with standard parameters. Secondary structure parameters of phosphoglucosamine mutase are presented in a tabulated form in Table 2, which shows it contains 42.64% alpha helix, 18.80% extended strand, 9.89% beta turn, and 29.69% random coil. The graphical secondary structure of phosphoglucosamine mutase is shown in Fig. 1.

Calculated secondary structure elements of phosphoglucosamine mutase of Legionella pneumophila by SOPMA

Predicted secondary structure of phosphoglucosamine mutase. Here, helix is indicated by blue, while extended strands and beta turns are indicated by red and green, respectively.

PPI network generation has become very important tool of the modern biomedical research arena for the understanding of complex molecular mechanisms and the detection of novel modulators of disease processes. These types of work have been shown to be very important in the study of a wide range of human diseases, as well as their signaling pathways [29, 30, 31]. PPI of phosphoglucosamine mutase was generated through STRING, presented in Fig. 2. STRING forecasts a confidence score and 3D structures of protein and protein domains. Confidence scores were generated on the basis of different parameters, like neighborhood, co-occurrence, coexpression, and homology. STRING utilizes references from UniProt and predicts functions of different interacting proteins. PPI network demonstrates that phosphoglucosamine mutase interacts with 10 other proteins, such as mur E is hypothetical protein with a confidence score of 0.687; glmU is bifunctional N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate (Glc-N-1-P) uridyltransferase/glucosamine-1-phosphate N-acetyltransferase (UDP-GlcNAc), which catalyzes the last two sequential reactions in the de novo biosynthetic pathway for UDP-GlcNAc. It is also responsible for the acetylation of Glc-N-1-P to give GlcNAc-1-P and for the uridyl transfer from UTP to GlcNAc-1-P, which produces UDP-GlcNAc. This protein is closely related to glmM with the highest confidence score (0.998). The second highest confidence protein is glmS, glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase, which catalyzes the first step in hexosamine metabolism, converting fructose-6P into glucosamine-6P using glutamine as a nitrogen source. Another important protein, murC (confidence score, 0.667), UDP-N-acetylmuramate-L-alanine ligase, works in cell wall formation.

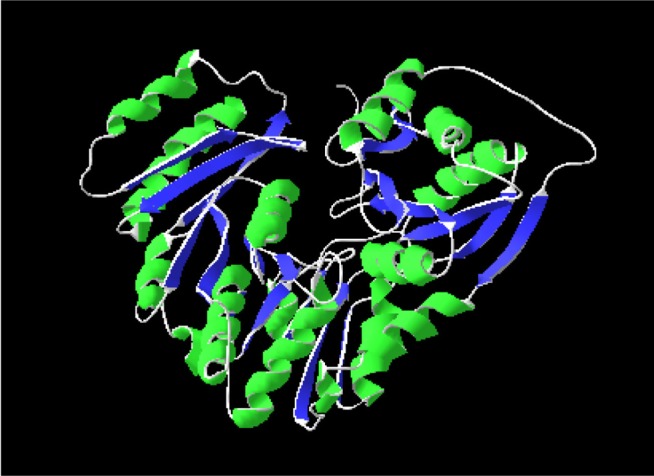

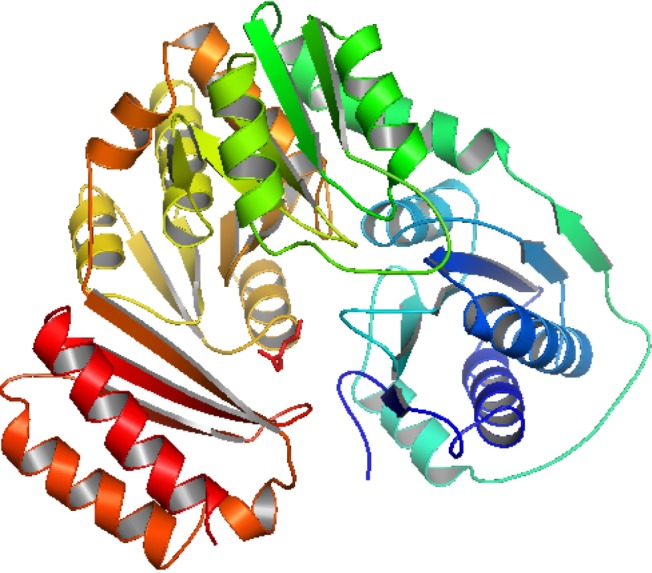

Homology modeling of the unique and essential metabolic protein was done by using Phyre2 in order to obtain the 3D structure of them. 3D protein structures give important insights about the molecular basis of protein function and thereby allow an effective design of experiments [32]. That is why, in the understanding and manipulation of biochemical and cellular functions of proteins, the high-resolution 3D structure of a protein is the main key [19]. Phyre2 generated the best suited result, showing that the predicted structure had a 100% confidence level and uses the template c3pdkB. Secondary structure and disorder prediction leads to a conclusion that phosphoglucosamine mutase has disordered region of 4%. To gain a more accurate model, refinement through ModRefiner was done.

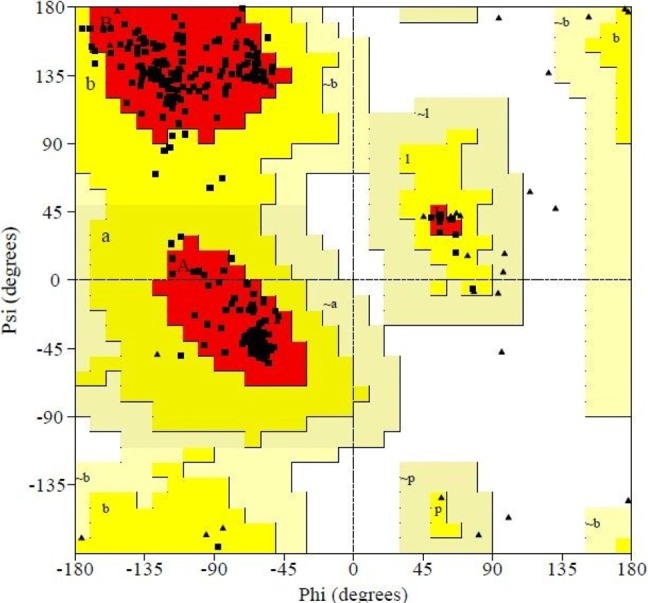

After derivation by the ModRefiner, the refined model (Fig. 3) of the desired enzyme was analyzed for further advancement. In the initial model of phosphoglucosamine mutase, the percent of residues in the favored region in the Ramachandran plot was 84.0% versus 95.0% in the final model. The red, brown, and yellow colored regions are the symbol of the favored, allowed, and generously allowed regions, respectively, the same as defined by PROCHECK (Fig. 4). Parameters, such as residue in the favored, allowed, and generously allowed region and G-factor, are the determinants of a good model [33, 34, 35].

Subsequent to that, PROCHECK was used to measure the accuracy of protein models. Parameter comparisons of these proteins were made with well-refined structures that have similar resolution. Through PROCHECK analysis, specific information about the protein chains and their stereochemical quality, like Ramachandran plot quality, peptide bond planarity, bad non-bonded interactions, main chain hydrogen bond energy, C alpha chirality, and overall G factor, and the side chain parameters like standard deviations of chi1 gauche minus, can be obtained [36]. Ramachandran plot statistics of phosphoglucosamine mutase revealed that most of the amino acid residues (above 90% of amino acid residues) were present in most favored regions (Table 3). Thus, the protein model was very good, seeing that all of the residues were within the limits of the Ramachandran plot.

Ramachandran plot statistics of phosphoglucosamine mutase from Legionella pneumophila (strain Paris)

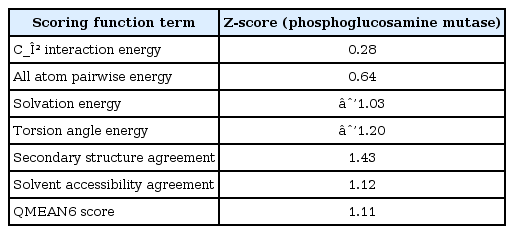

Verification was also done by ERRAT, Verify3D, and QMEAN server. ERRAT uses a quadratic error function to characterize and differentiate between correctly and incorrectly determined regions of protein structures based on characteristic atomic interaction [37]. The overall quality of the model by ERRAT analysis was 89.791. The Verify3D graph value of the model is 0.71, which indicates that the environmental profile of phosphoglucosamine mutase is quite good [38, 39, 40]. On the basis of a linear combination of six structural descriptions, the QMEAN scoring function estimates the global quality of the models. The local geometry model analysis is done by a torsion angel potential over three consecutive amino acids, and the quality of the model can be compared to a reference structure of high resolution obtained from X-ray crystallography analysis through Z score. QMEAN Z-score provides an estimation of the "degree of nativeness" of the structural features observed in a model and indicates that the model is of comparable quality to experimental structures [41].

The assessing of long-range interactions is carried through secondary structure specific distance-dependent pairwise residue level potential. A solvation potential describes the burial status of the residues. Secondary structure element and accessibility agreement ensures the quality assessment between the predicted and calculated secondary structure and solvent accessibility [21].

The respective values of Z-scores of C_β interaction energy, solvation energy, torsion angle energy, secondary structure, and solvent accessibility are 0.28, -1.03, -1.20, 1.43, and 1.12 in the case of phosphoglucosamine mutase, as shown in Table 4. The overall QMEAN score for phosphoglucosamine mutase is 1.11. QMEAN-generated results confer phosphoglucosamine mutase as a qualified model for further drug target scopes.

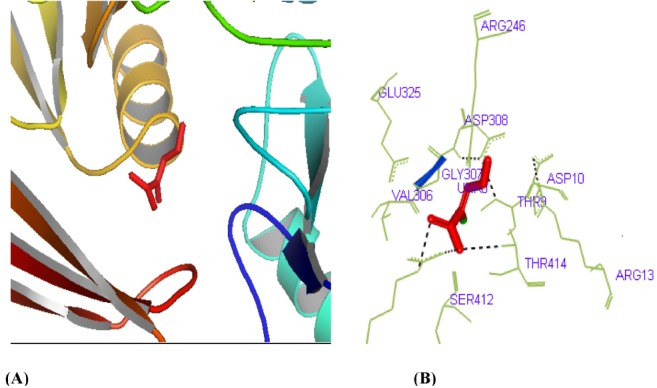

The active site of phosphoglucosamine mutase was predicted by using CASTp server. Further, in this study, we have also reported the best active site area of the experimental enzyme, as well as the number of amino acids involved in it. Fig. 5 shows the interacting residues Arg419, Thr414, Ser412, and Thr9 with protein-ligand from the docking that had been suggested by CASTp which was found in the active site of phosphoglucosamine mutase.

Active site determination of the phosphoglucosamine mutase protein. (A) The green region indicates the most potent active site. (B) The amino acid residues in the active site.

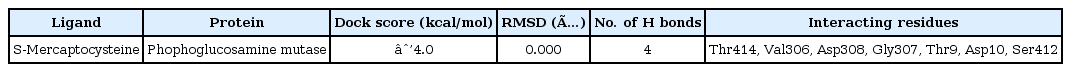

In order to understand docking studies with phosphoglucosamine mutase and s-mercaptocysteine, analysis of lowest docked energy value, calculated Root mean square deviation value, involvement of H bonds, and interacting residues was considered (Table 5). Least docked energy postulates a better docking result. Receptor-ligand analysis of our predicted protein shows the lowest energy of -4.0 kcal/mol, as well as a root mean square distance of 0.000 Å, and it contains four hydrogen bonds. Thr414, Val306, Asp308, Gly307, Thr9, Asp10, and Ser412 are the interacting molecules where ligand interacts with the protein receptor. S-mercaptocysteine (3-disulfanyl-L-alanine (2R)-2-amino-3-disulfanyl-propanoic acid), which has a molecular weight of 153.22 g/mol (Table 6), was found to bind at the active site of phosphoglucosamine mutase with the lowest binding energy (Fig. 6). It has been clear that s-mercaptocysteine formed similar hydrogen bond interactions with phosphoglucosamine mutase. From the active site analysis, 41 amino acid residues were found in the potent active site. The interaction between the active site residues and the ligand found in our present study is useful for perceiving the potential mechanism of residues and the drug binding. The hydrogen bonds play a significant role for the structure and function of biological molecules, and we found significant results. Among the 41 residues, Thr9, Arg246, Val306, Gly307, Asp308, Ser412, and Thr414 interacted with the ligand; the others did not. Docking analysis with ligand identified specific residues-viz. Thr414, Ser412, and Thr9 (Fig. 7)-within the phosphoglucosamine mutase binding pocket to play an important role in ligand binding affinity, which further itself inhibits its function and exposes studies about new drug discovery.

Graphical representation of docking study between S-mercaptocysteine and phosphoglucosamine mutase (yellow dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds). (A) Visualization of S-mercaptocysteine-phosphoglucosamine mutase. (B) Hydrogen bond detection through PyMOL.

The putative drug targets phosphoglucosamine mutase, phosphoglyceromutase, and phosphomannomutase for legionellosis have been reported as potential in the literature. That is why in our study, the 3D structure of phosphoglucosamine mutase from L. pneumophila (strain Paris) was predicted and validated by a variety of bioinformatics tools and software. Analyzing the results, it could be concluded that future characterization of phosphoglucosamine mutase from L. pneumophila (strain Paris) will be noteworthy for the regulation of legionellosis. The modeled 3D structure will provide a good-quality foundation for experimental development of the crystal structure, and the molecular docking study will assist efficient inhibitor design against legionellosis in the future.