Bioprospecting Potential of the Soil Metagenome: Novel Enzymes and Bioactivities

Article information

Abstract

The microbial diversity in soil ecosystems is higher than in any other microbial ecosystem. The majority of soil microorganisms has not been characterized, because the dominant members have not been readily culturable on standard cultivation media; therefore, the soil ecosystem is a great reservoir for the discovery of novel microbial enzymes and bioactivities. The soil metagenome, the collective microbial genome, could be cloned and sequenced directly from soils to search for novel microbial resources. This review summarizes the microbial diversity in soils and the efforts to search for microbial resources from the soil metagenome, with more emphasis on the potential of bioprospecting metagenomics and recent discoveries.

Soil Microbial Diversity

In 1898, a microbiologist, Heinrich Winterberg, first described that there was a discrepancy in the number of microorganisms between culturable bacteria on nutrient media and the total bacteria in nature counted by microscopy. Since then, microbial unculturability, the so-called 'great plate count anomaly,' has long been recognized in microbiology [1]. While microbial unculturability is not fully understood so far, microbial diversity has been analyzed extensively in various environments. This was mostly due to the advance of a molecular microbial ecology. The development of culture-independent analysis adopted amplification and DNA sequencing of microbial signature rRNA sequences from nature without cultivation of entire microbial species [2]. Therefore, analysis of the microbial phylogenetic marker genes, such as the 16S rRNA gene, revealed that microorganisms are the true dominant organism in nature [3]. The number of prokaryotic cells was estimated to be 4-6 × 1030 cells on Earth, and the prokaryotes represent the largest pool of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus among living organisms [4]. Microbial diversity has also been recognized from various soils, and only a small fraction of total microbial species in soil (i.e., less than 1%) has been characterized by cultivation-based methods [5, 6]. Since the majority of unculturable bacteria in soil has not been cultured [7], it has not been functionally characterized.

The microbial diversity in soil is probably highest compared to other microbial communities. Culture-independent analysis of microbial diversity in soil revealed that most bacterial members abundant in soils are members of the phyla Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Actinobacterium, Firmicutes, and some Verrucomicrobia [8, 9], showing that a large number of the 16S rRNA gene clones originated from uncultured bacterial species. The abundance of the members was somewhat variable in different types of soil. For example, the forest soils retained higher members of the phylum Acidobacteria but fewer β-proteobacterial members [10]. On the other hand, agricultural soils harbor higher numbers of members in β-proteobacteria but less Acidobacteria. The interesting result recently reported by Mendes et al. [11] indicated that the relative abundance of bacterial phyla, not their profiles, could be important for microbial community function in a specific soil, such as disease-suppressive soil.

Metagenome

The metagenome is the total microbial genome isolated directly from microorganisms in nature. The first proposal of the term 'metagenome' was by Handelsman et al. [12], while the first approach using environmental DNA was reported in 1995 to search for genes encoding cellulases [13]. The soil metagenome can be isolated directly from various types of soil either directly or indirectly without bacterial cultivation [14-16]. While the microbial diversities of various microbial habitats are being actively investigated by taking advantage of next-generation sequencing technology to analyze a large number of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequences derived from a variety of soils [8], the advances in bioprospecting metagenomics are relatively slow.

As a bioprospecting purpose, the purified soil metagenomic DNA would be cloned into several different plasmid vectors. In general, high-molecular-weight DNAs cloned into fosmid, cosmid, or bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vectors are introduced into a surrogate host bacterium, such as Escherichia coli [17]. Especially, the fosmid-based preparation of a metagenomic library is the most frequently used strategy, due to their high cloning efficiency, the improved stability in E. coli, and the feasibility to construct a medium-sized (40 kb)-insert DNA library [18]. Considering the low frequency of finding genes for novel bioactivities from a soil metagenomic library [19], the cloning efficiency is a crucial factor to construct a large clone member library. One of the most critical steps for successful library construction is the isolation of pure high-molecular-weight DNA, which is suitable for cloning into the vectors [8, 20]. However, high contents of soil-derived humic acids are co-purified during the high-molecular-weight DNA isolation process, and humic acids interfere with the cloning process of high-molecular-weight DNA into a vector. Various methods to remove humic acids during soil metagenomic DNA purification usually end up with the recovery of relatively low-molecular-weight DNA, which is not suitable to clone into a fosmid or BAC. Several commercial kits would be plausible to purify soil metagenomic DNA for the amplification purpose of 16S rRNA genes, which will be subsequently used for microbial diversity analysis. However, the sizes of DNA fragments isolated by most of the commercial kits are rather small to clone into vectors, such as fosmids and BACs. Therefore, optimal methods for the direct isolation of high-molecular-weight DNA from soil have been developed and used for bioprospecting metagenomics [14, 16, 20]. Although obtaining a large number of metagenomic clones from soil is a prerequisite to search for novel microbial genes from soil, the technologies for metagenomic library construction were generalized using fosmids and cosmids. Various novel microbial resources could be expected from soil metagenomic libraries, because soils bear the highest microbial diversity compared to any other microbial community.

Tapping soil metagenome

Since functional metagenomics (or bioprospecting metagenomics) was attempted from a soil ecosystem [17], a number of microbial genes encoding novel enzymes or bioactive compounds have been identified and characterized [21, 22]. Here, we summarize several technical points to be considered for bioprospecting metagenomics and the major results of novel enzymes and bioactivities from the soil metagenome.

Screening strategies and high-throughput screening (HTS)

Metagenomic libraries with either large-insert DNA or small-insert DNA were used to search for novel microbial genes. The library with the small-insert DNA could be feasible to identify novel enzymes, while that with the large-insert DNA is also frequently used [23]. Screening of both types of metagenomic libraries has been conducted and successfully identified many novel enzymes and bioactivities [21]. Two different approaches for screening the metagenomic libraries are frequently used, such as function-based (expression-dependent) screening and sequence-based (homology-dependent) screening.

Function-based screening is dependent on the expression of metagenomic genes in a surrogate host, such as E. coli, and subsequently detects metabolic activities in the heterologous host. Therefore, the proper expression of metagenomic genes is essential to detect the phenotypic characteristics of the desired activity by the function-based screening approach. It is arguable that the majority of genes from uncultured soil microorganisms would not be expressed properly in a host bacterium. There has been no extensive analysis to assess the expression ratio of metagenomic genes in defined culturable bacteria. In spite of the expression barrier of cloned metagenomic genes in E. coli, the function-driven approach has proven to be feasible to search for novel genes and gene products [22]. Recently, function-based screening approaches have been advanced and modified to search for novel microbial genes compared with the original approach-i.e., the direct detection of metabolic function [17]. Host strains or mutants were used to identify genes for functional complementation in trans by metagenomic clones [24], and another advance in function-based screening was combined with HTS to detect the induced gene expression in a host bacterium with substrates, autoinducers, and metabolic products provided exogenously [25-27]. One of the approaches to overcome the host expression barrier is to develop a broad-host range vector to express a metagenomic library in a variety of host bacteria. This approach, in fact, is promising and nourishing the function-based screening of metagenomics to obtain diverse microbial resources for enzymes and biomolecules [28].

The sequence-based approach is to screen for marker genes using DNA probe or PCR primers designed from DNA sequences of already known genes. Since this approach would detect gene variants with the conserved motif from the metagenome, it is arguable if this approach would really screen true novel genes from microbial diversity. Nevertheless, there are a number of examples with some successful identification of novel microbial enzymes [22, 29]. A recent approach with sequence-based screening is taking advantage of the advances in next-generation sequencing. Direct sequencing of metagenomic DNA by next-generation sequencing is now used increasingly to study gene inventories in the metagenomes of specific microbial communities [30]. Direct sequencing of a metagenome generates a large dataset, which should be analyzed by support of the appropriate informatics. Analysis of the soil metagenome by the sequencing-based approach is still a huge challenge, since the soil microbial community is the most complicated one with the highest microbial diversity compared with any other microbial community. A combination of appropriate bioinformatics, such as comparative sequence analysis, with the large set of soil metagenome sequences will be a new opportunity to search for microbial enzymes and novel bioactivities in the future [31]. HTS is another issue for bioprospecting metagenomics with the direct sequencing of the metagenome. If both function-based and sequence-based screening is combined with HTS, novel microbial enzymes and bioactivities would be detected at higher frequency compared with conventional screening. This is mainly because the large numbers of metagenomic clones in libraries should be searched for novel enzymes and biomolecules to tap the great soil microbial diversity. Some of the recently adopted HTS methods for drug discovery may enable the discovery of novel enzymes and biomolecules from the soil metagenome. Multidisciplinary efforts, combined with bioinformatics, analytical chemistry, and high-throughput technology, is required to search for novel enzymes and bioactivities from soil metagenomes.

Novel enzymes from soil metagenome

Many novel enzymes were identified from various metagenomic studies, and we summarized the examples of enzyme recovery from soil metagenome studies in Table 1 [10, 32-58]. One of the most prevailing novel enzymes found from the soil metagenome is esterase/lipase. Lipolytic enzymes, such as esterases and lipases, are important biocatalysts for biotechnological applications. The interesting features of lipolytic enzymes include no requirement for cofactors, remarkable stability in organic solvents, broad substrate specificity, stereoselectivity, and positional selectivity [23]. The features of lipolytic enzymes are especially attractive for organic synthesis if the enzymes with specific chiral resolution could be retrieved from the soil metagenome. Therefore, the discovery of novel lipolytic enzymes from the soil metagenome has received much attention compared to other enzymes. Considering that lipolytic enzymes are the most well characterized and highly studied enzymes among biocatalysts, the finding of several novel families of esterase/lipase enzymes is quite surprising. One of our previous results with EstD2 revealed that EstD2 was not similar to any previously described enzymes, while the enzyme clearly displayed esterase activity [39]. A similar protein found in the GenBank database also exhibited the same activity, while it was initially annotated as a hypothetical protein. Therefore, function-driven selection of EstD2 constituted a novel family of esterases and re-annotated many proteins as esterase/lipases that were previously known as hypothetical proteins. Similar studies with enzymes found in the soil metagenome suggested that soil microbial diversity truly bears the great extent of novel microbial enzymes.

Cellulolytic enzymes and cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs) of plant cells are also enzymes with biotechnological interest, mostly due to biomass degradation, with the purpose of bioenergy production. In contrast to the enzymatic interest, the identification of novel cellulolytic enzymes or other CWDEs is not well documented. The reason for the rare recovery of cellulases and CWDEs is poor secretion of these enzymes in E. coli, the major host bacteria, and incompatible detection methods of enzymatic activity for a large member of metagenomic libraries from the soil metagenome. For the successful detection of cellulases and CWDEs, technical elaboration with HTS would be necessary to enhance the detection of proper enzyme activity. Bioinformatics, such as comparative sequence analysis of the metagenome, could be another choice to identify cellulolytic enzymes and CWDEs from massive datasets derived from direct sequencing of the soil metagenome. A number of enzymes for other carbohydrate metabolism and a few lactonases were also detected from the soil metagenome, and they are listed in Table 1. However, many enzymes are not feasible to detection by simply screening for the bacterial phenotypic changes, while the lipolytic enzymes were simply identified by tributyrin hydrolysis on culture medium.

Bioactivities from soil metagenome

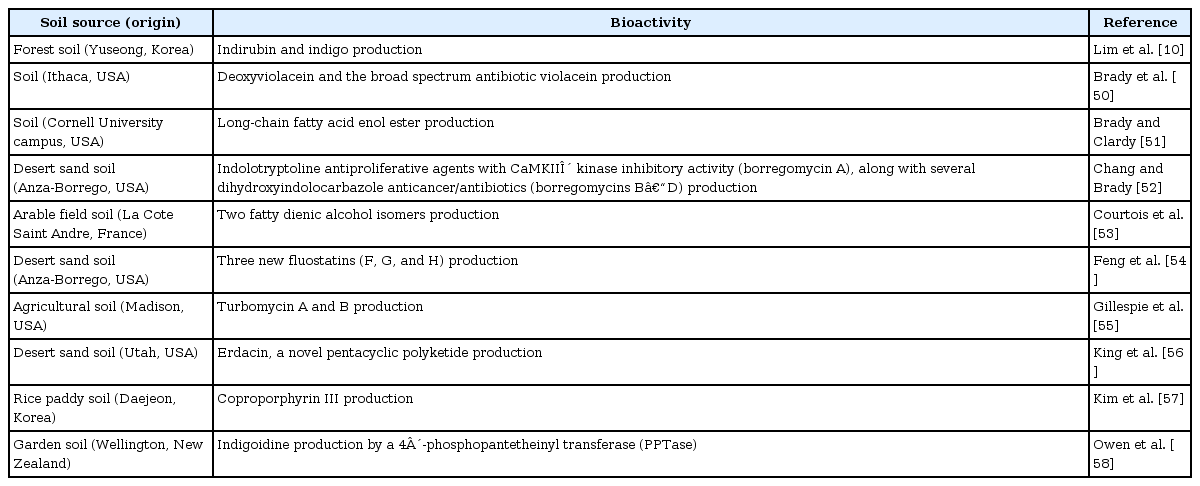

In addition to the novel enzymes, soil metagenomes are rich sources of a variety of small molecules with bioactivities, such as antibiotics and other pharmaceutically applicable activities. The search for novel bioactivities is primarily based on the phenotypic detection of bacterial traits of the host bacteria bearing metagenomic libraries. Antagonistic activity and colony color changes of the host bacterium are typical examples to detect metagenomic clones, potentially associated with novel secondary metabolite production. However, the conventional approach exhibits a rarer chance to identify novel gene clusters and bioactivities [19]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new detection strategies for novel bioactivities from the soil metagenome. Nonetheless, the simple detection of antibiosis or color changes of the host bacterial colonies with metagenomic clones brought some interesting results, suggesting the great potential of novel bioactivities from the soil metagenome. We summarize the identified bioactivities and their gene clusters from the soil metagenome in Table 2. These bioactivities include antibacterial turbomycins, glycopeptides, cyanobactins, type II polyketides, trans-acyltransferase polyketides, and the anticancer agent ET-743 [21]. Some of the bioactivities from the soil metagenome may also be discovered by homology-based screening. Whole metagenome sequences from soil, which will be accomplished in the future, would be a rich source to be probed to identify gene clusters for bioactive compound production.

Future Perspectives

The soil metagenome, a rich microbial source, is still unexplored, since major microbial species have not been cultured and characterized from various soils. Both function-driven metagenomics and homology-dependent metagenomics have started out in soils and brought some successful discovery of novel microbial enzymes and secondary metabolites. Further analysis of soil microbial communities and the appropriate enrichment of target resources from soils will increase the chance to discover novel microbial enzymes and bioactivities from the soil metagenome. In addition, the adoption of HTS, the advances in sequencing technology, and the proper bioinformatics would be necessary to improve the efficacy of bioprospecting metagenomics of soils for the discovery of novel enzymes and bioactivities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Mid-career Researcher Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2012R1A2A2A01045039) and by a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (No. PJ0082012013), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.