|

|

- Search

| Genomics Inform > Volume 10(1); 2012 > Article |

Abstract

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is the movement of genetic material between kingdoms and is considered to play a positive role in adaptation. Cryptosporidium parvum is a parasitic protozoan that causes an infectious disease. Its genome sequencing reported 14 bacteria-like proteins in the nuclear genome. Among them, cgd2_1810, which has been annotated as CysQ, a sulfite synthesis pathway protein, is listed as one of the candidates of genes horizontally transferred from bacterial origin. In this report, we examined this issue using phylogenetic analysis. Our BLAST search showed that C. parvum CysQ protein had the highest similarity with that of proteobacteria. Analysis with NCBI's Conserved Domain Tree showed phylogenetic incongruence, in that C. parvum CysQ protein was located within a branch of proteobacteria in the cd01638 domain, a bacterial member of the inositol monophosphatase family. According to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway, the sulfate assimilation pathway, where CysQ plays an important role, is well conserved in most eukaryotes as well as prokaryotes. However, the Apicomplexa, including C. parvum, largely lack orthologous genes of the pathway, suggesting its loss in those protozoan lineages. Therefore, we conclude that C. parvum regained cysQ from proteobacteria by HGT, although its functional role is elusive.

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is the movement of genetic material between different species of interkingdom, and lateral gene transfer is for intrakingdom movement [1]. The concept for gene transfer was first mentioned for an acquisition of virulence between bacterial strains [2], and then, transfers of multiple drug resistance between Shigellae and Escherichia coli strains were reported in Japan [3].

It is important to note that HGT not only affects correct reconstruction of a phylogenetic tree but also helps to understand reasons of its occurrence. In bacteria, it is widely known that genetic material of antibiotic resistance is transferred in the gastrointestinal tract [4], and in the case of unicellular eukaryotes, such as Giardia lamblia, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Entamoeba histolytica, the organisms that use fermentation or anaerobic metabolism in the low-oxygen environment overcame the environmental stress by taking genes from bacteria [5]. Moreover, the transferred gene plays a positive role in adaptation to a pathogenic way of life [6]. On the other hand, HGT has been criticized, in that its biological significance is overemphasized. If a gene has an essential role and participates in many interactions, its transfer might be less likely to occur than that of others or would be detrimental to the recipient. Thus, some transferred genes are considered nonfunctional [7-9].

Cryptosporidium is a parasitic protozoan of the phylum Apicomplexa. Among Cryptosporidium, C. parvum causes an infectious disease in humans and animals with diarrhea, called cryptosporidiosis. Although the disease is prevalent where water quality is poorly managed, there is no satisfactory treatment until now [10, 11].

Genome sequencing of C. parvum was completed in 2004, identifying major metabolic pathways through comparison with other parasites and also reporting those enzymes with high similarities to bacterial and plantal counterparts [12]. In some crucial biosynthesis pathways, C. parvum has enzymes that originated from various organisms, such as bacteria, plants, and algae. Phylogenomic analyses predicted a set of genes transferred from algae and eubacteria [13] and promising drug targets in nucleotide biosynthesis [14]. However, among 14 bacterial-like enzymes that were reported by Abrahamsen et al., only two enzymes received follow-up attention [15, 16].

CysQ, 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphatase, also known as 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphosulfate (PAPS) 3'-phosphatase, or 3'(2'), 5'-bisphosphate nucleotidase, was among the 14 bacterial-like enzymes initially reported by the genome analysis. It has been thought that it is needed during aerobic growth in E. coli to help control the levels of PAPS in cysteine biosynthesis [17]. Recently, CysQ protein has been considered as an important regulator that modulates the sulfate assimilation pathway by affecting levels of intermediates in plants, fungi, and bacteria [18, 19]. Despite its biological importance, no follow-up phylogenetic analysis of CysQ in C. parvum has been reported.

In this study, we assumed that CysQ might have been transferred from bacteria to C. parvum by horizontal gene transfer. We constructed phylogenetic trees, based on a conserved domain of the protein, and inferred HGT from the phylogenetic incongruence.

Cryptosporidium parvum strain Iowa type II (NCBI taxonomy accession 353152) was chosen for this study. One of its genes, cgd2_1810, encodes CysQ, a sulfite synthesis pathway protein (accession no. XP_001388206) [12]. The protein sequence was retrieved from the NCBI Protein Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein).

Sequence similarity searches were performed using BLASTP 2.2.26+ [20] with C. parvum CysQ protein against a nonredundant protein sequence database. TBLASTN 2.2.26+ [21] was performed in order to search for the orthologs of the sulfur metabolism pathway in the C. parvum genome sequence using E. coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein sequences as queries.

We obtained information of conserved domains using the NCBI online Conserved Domain-search tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) and Conserved Domain Database (CDD) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) [22, 23]. After the matching CDD model and the corresponding Conserved Domain Tree (CDTree) were identified, the CysQ sequence was added to the matched model, and the corresponding CDTree was then recalculated.

PhylomeDB is a collection of phylogenetic trees that have been precalculated automatically with a variety of options for a wide range of species [24]. We queried PhylomeDB and downloaded the phylogenetic trees that included CysQ protein.

CysQ enzyme was found in sulfate assimilation on sulfur metabolism of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway. The list of organisms that harbored this pathway was compiled from KEGG orthology (KO) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/ko.html) [25].

The BLAST run using the query sequence of Cryptosporidium parvum reported the proteins of the genus Cryptosporidium as the best hits, followed by those of the order Eucoccidiorida, the genus Cryptosporidium belongs to. The next best hits belonged mostly to Gammaproteobacteria. Their gene descriptions corresponded to one of the alternative names of CysQ protein or a member protein of the inositol monophosphatase family, except for unclassified proteins and hypothetical proteins. The best bacterial hit had an identity of 40% and a bit score of 181 bits for the query sequence of 341 amino acids. From the taxonomy report of the BLAST result, 11 organisms among 110 were eukaryotes, and the other 99 were bacteria. The bacterial list was composed of 59 Proteobacteria species, including 53 Gammaproteobacteria and 31 Bacteroidetes species.

While the BLAST analysis hinted HGT of the cysQ gene from bacteria to C. parvum, the hypothesis should be confirmed by phylogenetic analysis. A phylogenetic tree for CysQ protein was retrieved from PhylomeDB. We chose the Phy0018DKQ_ECOL5 tree made by the E. coli protein sequence as a seed and maximum likelihood method with the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) evolutionary model. The phylogenetic tree with 170 orthologs comprised three eukaryotes-C. parvum, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Oryza sativa-one Archaea, and 166 Bacteria species. In the tree, C. parvum was branched with Proteobacteria, while the plantal proteins were the outgroup of prokaryotic proteins.

In OrthoMCL (http://orthomcl.org), CysQ of C. parvum was located within the inositol monophosphatase family of Pfam (entry name OG5_129356) [26]. This ortholog group has only 70 orthologs from 54 different species and paralogs of Viridiplantae or T. vaginalis. Moreover, it included a larger portion of plants and fungi rather than bacteria, and no metazoan protein orthologs were included. Unlike PhylomeDB or OrthoMCL, the CDD of NCBI cataloged proteins sharing CysQ or related domains comprehensively.

CysQ protein of C. parvum contains a CysQ domain (accession no. cd01638), which is one of the children of the Fig (FBPase/inositol monophosphatase [IMPase]/glpX-like domain) superfamily. The Fig superfamily is a metal-dependent phosphatase that organizes two subsets of direct children in the hierarchy of the superfamily: FBPase glpX domain (cd01516) and IMPase-like domain (cd01637). Cd01637 has 9 children domains: CysQ (cd01638), IMPase (cd01639), bacterial IMPaselike 1 (cd01641), bacterial IMPase-like 2 (cd01643), IPPase (cd10640), FBPase (cd00354), Arch FBPase 1 (cd 01515), Arch FBPase 2 (cd01642), and PAP phosphatase (cd10517). The whole hierarchy tree of the Fig superfamily comprises a total of 360 cellular organisms: 246 bacteria, 95 eukaryotes, and 19 Archaea (Fig. 1A). Some domains (cd01516, cd01637, cd01638, cd01641, and cd0643) comprise predominantly bacterial proteins in their CDTree, whereas the other domains have a combined composition (cd000354, cd0517, and cd01639) or a high level of Archaea (cd01642 and cd01515). Domains cd01638, cd01641, and cd01643 are bacterial members of the IMPase family. All of them show a high proportion of Proteobacteria, at about 65%, 50%, and 43% respectively. In cd01638, C. parvum CysQ protein is located within the monophyletic gram-negative subtree, ranging from Pseudomonas sringae, Gammaproteobacteria, to Campylobacter jejuni, Epsilonproteobacteria (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, the gram-negative subtree is paraphyletic, in that it has 27 branches of Proteobacteria and Aquificae, Cyanobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, respectively. Taken together, the phylogenetic analysis strongly supports the hypothesis that the cysQ gene of C. parvum may have been acquired from Proteobacteria by horizontal gene transfer.

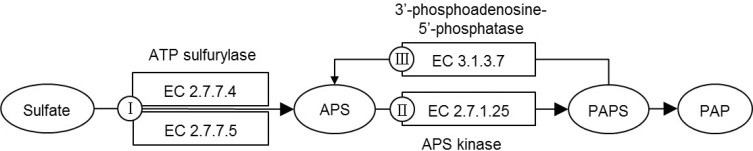

CysQ protein participates in sulfate assimilation on sulfur metabolism. In Fig. 2, we show a simplified version of the KEGG pathway, classifying the enzymes into three groups, according to their direction and steps: Class I for EC 2.7.7.4 (CysN) and EC 2.7.7.5 (CysD); Class II for EC 2.7.1.25 (CysC); and Class III for EC 3.1.3.7 (CysQ). If CysQ of C. parvum is a true CysQ enzyme, playing a role in sulfate assimilation in the parasite, the other components of the pathway should be present in it. On the contrary, we could not identify such genes in the annotated gene list.

The KEGG pathway did not list C. parvum proteins in the sulfate assimilation pathway. We looked for the C. parvum proteins by searching the genome sequence using TBLASTN with M. tuberculosis CysN (Rv1286) and CysD (Rv1285) and E. coli CysN (b2751), CysD (b2752), and CysC (b2750) proteins as queries.

Among class I and II proteins, only CysN showed marginal matches to cgd6_3990 (29% and 33% identities, respectively) to M. tuberculosis and E. coli sequences. Interestingly, this C. parvum protein was reported as elongation factor 1 alpha, not a sulfate adenylyltransferase. This protein had high similarities to other protozoan or fungal elongation factor 1 alpha proteins. Thus, we consider this as a false hit. The class III protein, CysQ, matched to cgd2_1810 (24% and 36% identities, respectively, for M. tuberculosis and E. coli proteins). This C. parvum gene was annotated "CysQ, sulfite synthesis pathway protein." As no other components of the sulfate assimilation pathway, except for CysQ, are found in C. parvum, we may conclude that the pathway does not function in this organism. We compiled the orthologs of the genes in this pathway using the KO database (Table 1).

Eukaryotic kingdoms, except for protists harbored full ranges of orthologs in all three classes. Animals and plants showed similar trends in Class I and II, because two classes shared two orthologs (K13811: 3'-phosphoadenosine 5'-phosphosulfate synthase [PAPSS], K00955: bifunctional enzyme CysN/CysC [CysNC]), and even K13811 is specialized in animals and plants. Fungi also have many orthologs, like animals and plants, in Class I and II, but they have different orthologs (Class I, K00958, sulfate adenylyltransferase [E2.7.7.4C, met3]; Class II, K00860, adenylylsulfatekinase [CysC]).

In prokaryotes, the proportion of Class I genes is higher than Class II. All Cyanobacteria, two-thirds of Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria contained one of the orthologs in Class I, whereas Firmicutes, other bacteria, and the Archaea group have a few orthologs in Class I, II, and III.

On the other hand, there were very few orthologs of the sulfate assimilation pathway in protists. We expanded the protist lineage, cataloging the proteins at the class or species level (Table 2).

Some protists (Choanoflagellates, Entamoeba of Amoebozoa, and Diatoms) had at least one orthologous gene in each of three classes, while most Alveolates, Amoeboflagellate, Euglenozoa, and Diplomonads did not have any orthologs in three classes, many of which are known as parasites causing infectious diseases.

While the sulfate assimilation pathway is generally well conserved in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, in some protist lineages, the pathway is missing. Thus, we hypothesize that the pathway may have been lost during the evolution of the lineages. C. parvum, like other Aveolates, also may have lost it, and cge2_1810 can not function as CysQ properly. Its function remains elusive, as the sequence similarity to CysQ of M. tuberculosis or E. coli is rather low.

A BLAST search of C. parvum CysQ (cgd2_1810) protein shows the highest similarity with those of proteobacteria. Although it implies HGT from bacteria to this eukaryote, sequence similarity alone is not enough as its basis for several known reasons [27].

In addition, a phylogenetic analysis should support it. For this, initially, we relied on the tree built by PhylomeDB. However, its species coverage was biased or undersampled. On the other hand, CDD of NCBI is well subdivided into kingdom and function groups. C. parvum CysQ protein was mapped into the subfamily of IMPase, which is a bacterial CysQ domain, and comprises only bacterial sequences. Furthermore, C. parvum was located near Gamma- and Alphaproteobacteria in the CDTree. Hence, it seems that these results demonstrate that gene transfer events occurred from bacteria to C. parvum in the evolutionary process.

On the KEGG pathway, we raise the possibility that Alveolates, Euglenozoa, and Diplomonads of protozoa suffered from the losses of genes in the sulfate assimilation pathway. But, did C. parvum recover CysQ protein by HGT in the process of evolution? Sulfate assimilation shows highly conserved orthologs for each taxonomy lineage, and it plays important roles in sulfur metabolism, whereas Alveolates of protozoa, including Cryptosporidium, rarely have orthologous genes. For the pathogenic bacterium M. tuberculosis, sulfur-containing metabolites are essential to its pathogenesis and persistence in the host [18, 28], and the Database of Essential Genes (DEG) lists that Rv1286 (cysN) and Rv1285 (cysD), not Rv2131c (cysQ), are essential genes in sulfur metabolism of M. tuberculosis [29, 30]. Parasitic protozoa have diverse sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism that are considered to affect virulence and several stress response. On the other hand, C. parvum and Plasmodium falciparum lack a sulfur assimilation pathway, which is expected to be substituted from host cells [31].

In conclusion, although the sulfate assimilation pathway is missing in some protest lineages, C. parvum has a protein that is predicted as CysQ and has sequence similarity with that of proteobacteria, gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, the phylogenetic analysis supports the acquisition of cgd2_1810 from proteobacteria through horizontal gene transfer. Therefore, we can infer that C. parvum lost its genes in the sulfate assimilation pathway, including cysQ, during a parasitic way of life, and it acquired a copy of cysQ from bacteria by horizontal gene transfer. What is the biological role of this gene product? As the sole member, without other members, of the pathway, it can not assume the right role of CysQ. Its function is elusive at the moment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) (R11-2008-062-03003-0), funded by the Korea government (MEST).

References

1. Syvanen M, Kado CI. Horizontal Gene Transfer. 2002. London: Academic Press.

2. Freeman VJ. Studies on the virulence of bacteriophage-infected strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J Bacteriol 1951;61:675–688. PMID: 14850426.

3. Watanabe T. Infective heredity of multiple drug resistance in bacteria. Bacteriol Rev 1963;27:87–115. PMID: 13999115.

4. Kelly BG, Vespermann A, Bolton DJ. Gene transfer events and their occurrence in selected environments. Food Chem Toxicol 2009;47:978–983. PMID: 18639605.

5. Keeling PJ, Palmer JD. Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution. Nat Rev Genet 2008;9:605–618. PMID: 18591983.

6. Keeling PJ. Functional and ecological impacts of horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2009;19:613–619. PMID: 19897356.

7. Woolfit M, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, McGraw EA, O'Neill SL. An ancient horizontal gene transfer between mosquito and the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia pipientis. Mol Biol Evol 2009;26:367–374. PMID: 18988686.

8. Mallet LV, Becq J, Deschavanne P. Whole genome evaluation of horizontal transfers in the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. BMC Genomics 2010;11:171. PMID: 20226043.

9. Vogan AA, Higgs PG. The advantages and disadvantages of horizontal gene transfer and the emergence of the first species. Biol Direct 2011;6:1. PMID: 21199581.

10. DuPont HL, Chappell CL, Sterling CR, Okhuysen PC, Rose JB, Jakubowski W. The infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum in healthy volunteers. N Engl J Med 1995;332:855–859. PMID: 7870140.

11. Park JH, Kim HJ, Guk SM, Shin EH, Kim JL, Rim HJ, et al. A survey of cryptosporidiosis among 2,541 residents of 25 coastal islands in Jeollanam-Do (Province), Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol 2006;44:367–372. PMID: 17170579.

12. Abrahamsen MS, Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Abrahante JE, Zhu G, Lancto CA, et al. Complete genome sequence of the apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum. Science 2004;304:441–445. PMID: 15044751.

13. Huang J, Mullapudi N, Lancto CA, Scott M, Abrahamsen MS, Kissinger JC. Phylogenomic evidence supports past endosymbiosis, intracellular and horizontal gene transfer in Cryptosporidium parvum. Genome Biol 2004;5:R88. PMID: 15535864.

14. Striepen B, Pruijssers AJ, Huang J, Li C, Gubbels MJ, Umejiego NN, et al. Gene transfer in the evolution of parasite nucleotide biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:3154–3159. PMID: 14973196.

15. Chaudhary K, Roos DS. Protozoan genomics for drug discovery. Nat Biotechnol 2005;23:1089–1091. PMID: 16151400.

16. Umejiego NN, Gollapalli D, Sharling L, Volftsun A, Lu J, Benjamin NN, et al. Targeting a prokaryotic protein in a eukaryotic pathogen: identification of lead compounds against cryptosporidiosis. Chem Biol 2008;15:70–77. PMID: 18215774.

17. Neuwald AF, Krishnan BR, Brikun I, Kulakauskas S, Suziedelis K, Tomcsanyi T, et al. cysQ, a gene needed for cysteine synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12 only during aerobic growth. J Bacteriol 1992;174:415–425. PMID: 1729235.

18. Hatzios SK, Iavarone AT, Bertozzi CR. Rv2131c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a CysQ 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphatase. Biochemistry 2008;47:5823–5831. PMID: 18454554.

19. Hatzios SK, Schelle MW, Newton GL, Sogi KM, Holsclaw CM, Fahey RC, et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis CysQ phosphatase modulates the biosynthesis of sulfated glycolipids and bacterial growth. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011;21:4956–4959. PMID: 21795043.

20. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990;215:403–410. PMID: 2231712.

21. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997;25:3389–3402. PMID: 9254694.

22. Marchler-Bauer A, Bryant SH. CD-Search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32:W327–W331. PMID: 15215404.

23. Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D225–D229. PMID: 21109532.

24. Huerta-Cepas J, Capella-Gutierrez S, Pryszcz LP, Denisov I, Kormes D, Marcet-Houben M, et al. PhylomeDB v3.0: an expanding repository of genome-wide collections of trees, alignments and phylogeny-based orthology and paralogy predictions. Nucleic Acids Res 2011;39:D556–D560. PMID: 21075798.

25. Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Okuno Y, Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32:D277–D280. PMID: 14681412.

26. Chen F, Mackey AJ, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL-DB: querying a comprehensive multi-species collection of ortholog groups. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:D363–D368. PMID: 16381887.

27. Koski LB, Golding GB. The closest BLAST hit is often not the nearest neighbor. J Mol Evol 2001;52:540–542. PMID: 11443357.

28. Hatzios SK, Bertozzi CR. The regulation of sulfur metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog 2011;7:e1002036. PMID: 21811406.

29. Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 2003;48:77–84. PMID: 12657046.

30. Zhang R, Lin Y. DEG 5.0, a database of essential genes in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:D455–D458. PMID: 18974178.

31. Nozaki T, Ali V, Tokoro M. Sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism in parasitic protozoa. Adv Parasitol 2005;60:1–99. PMID: 16230102.

Fig. 1

Conserved Domain Tree (CDTree) involving CysQ (cgd2_1810) protein. (A) Whole hierarchy of Fig superfamily. Branch colors indicate Eukaryota (pink), Bacteria (bright blue), and Archaea (orange) domains; Cryptosporidium parvum sequence is added (red branch and circle). On the right side, color bar marked with domain accession names displays subfamilies in Fig superfamily. All CDs except for cd01637 are well clustered. cd01637 is scattered around the tree and highlighted in black ticks. (B) CDTree of cd01638 domain. The cd01638 clade that includes only bacteria is classified by taxonomic lineage. Bacteria are subdivided into two distinct parts, gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Each bacterial phylum is colored as shown in legend. CysQ protein of C. parvum is shown in red dashed branch with a red circle near Proteobacteria.

Fig. 2

A simplified sulfate assimilation pathway. Inorganic sulfate is converted to adenosine 5'-phosphosulfate (APS) by ATP sulfurylase (EC 2.7.7.4 and/or EC 2.7.7.5, Class I). APS is phosphorylated by APS kinase (EC 2.7.1.25, Class II) to 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphosulfate (PAPS). PAPS is either transferred to 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphate (PAP) or reconverted to APS by 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.7, Class III).

Table 1.

Class comparison of ortholog conservation in cellular organismsa

| Kingdom or phyla | Class I | Class II | Class III | Total no. of organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conservation stateb (Maxc (Avrgd)) |

||||

| Animals | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | 52 |

| 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 96 (92) | ||

| Fungi | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | 53 |

| 94 (48) | 83 (83) | 94 (94) | ||

| Plants | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | 15 |

| 73 (57) | 93 (83) | 87 (80) | ||

| Protists | + | + | ++ | 31 |

| 19 (16) | 13 (11) | 26 (26) | ||

| Proteobacteria | +++ | ++ | +++ | 656 |

| 71 (31) | 45 (23) | 67 (67) | ||

| Firmicutes | ++ | ++ | + | 303 |

| 26 (11) | 26 (16) | 0.3 (0.3) | ||

| Actinobacteria | +++ | ++ | ++ | 145 |

| 66 (38) | 34 (24) | 48 (48) | ||

| Cyanobacteria | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | 40 |

| 100 (100) | 93 (93) | 100 (100) | ||

| Other Bacteria | ++ | + | + | 258 |

| 28 (17) | 21 (14) | 21 (21) | ||

| Archaea | ++ | ++ | + | 117 |

| 40 (40) | 26 (26) | 2 (2) | ||

a Each class (see the caption of Fig. 2 for abbreviations of classes) consists of several orthologs and it follows the reference pathway of KEGG Ortholog (KO);

Table 2.

Protist orthologs involved in sulfate assimilation pathway

| Organism |

Orthologs in Classa |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Class I |

Class II |

Class III |

|||||||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | A | B | G | H | I | J | ||||

| Protists | Choanoflagellates | Monosiga brevicollis | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||

| Amoeboflagellate | Naegleria gruberi | ||||||||||||||

| Amoebozoa | Dictyostelium | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Entamoeba | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Alveolates | Apicomplexans | Plasmodium | |||||||||||||

| Theileria annulata | |||||||||||||||

| Babesia bovis | |||||||||||||||

| Cryptosporidium | |||||||||||||||

| Toxoplasma | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Ciliates | Tetrahymena | ||||||||||||||

| Paramecium | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Euglenozoa | Kinetoplasts | Trypanosoma | |||||||||||||

| Leishmania | |||||||||||||||

| Diplomonads | Giardia | ||||||||||||||

| Parabasalids | T. vaginalis | ● | |||||||||||||

| Diatoms | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||

| Thalassiosira pseudonana | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||

| Oomycetes | Phytophthora | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

- TOOLS

- Related articles in GNI