Comparative Evaluation of Intron Prediction Methods and Detection of Plant Genome Annotation Using Intron Length Distributions

Article information

Abstract

Intron prediction is an important problem of the constantly updated genome annotation. Using two model plant (rice and Arabidopsis) genomes, we compared two well-known intron prediction tools: the Blast-Like Alignment Tool (BLAT) and Sim4cc. The results showed that each of the tools had its own advantages and disadvantages. BLAT predicted more than 99% introns of whole genomic introns with a small number of false-positive introns. Sim4cc was successful at finding the correct introns with a false-negative rate of 1.02% to 4.85%, and it needed a longer run time than BLAT. Further, we evaluated the intron information of 10 complete plant genomes. As non-coding sequences, intron lengths are not limited by a triplet codon frame; so, intron lengths have three phases: a multiple of three bases (3n), a multiple of three bases plus one (3n + 1), and a multiple of three bases plus two (3n + 2). It was widely accepted that the percentages of the 3n, 3n + 1, and 3n + 2 introns were quite similar in genomes. Our studies showed that 80% (8/10) of species were similar in terms of the number of three phases. The percentages of 3n introns in Ostreococcus lucimarinus was excessive (47.7%), while in Ostreococcus tauri, it was deficient (29.1%). This discrepancy could have been the result of errors in intron prediction. It is suggested that a three-phase evaluation is a fast and effective method of detecting intron annotation problems.

Introduction

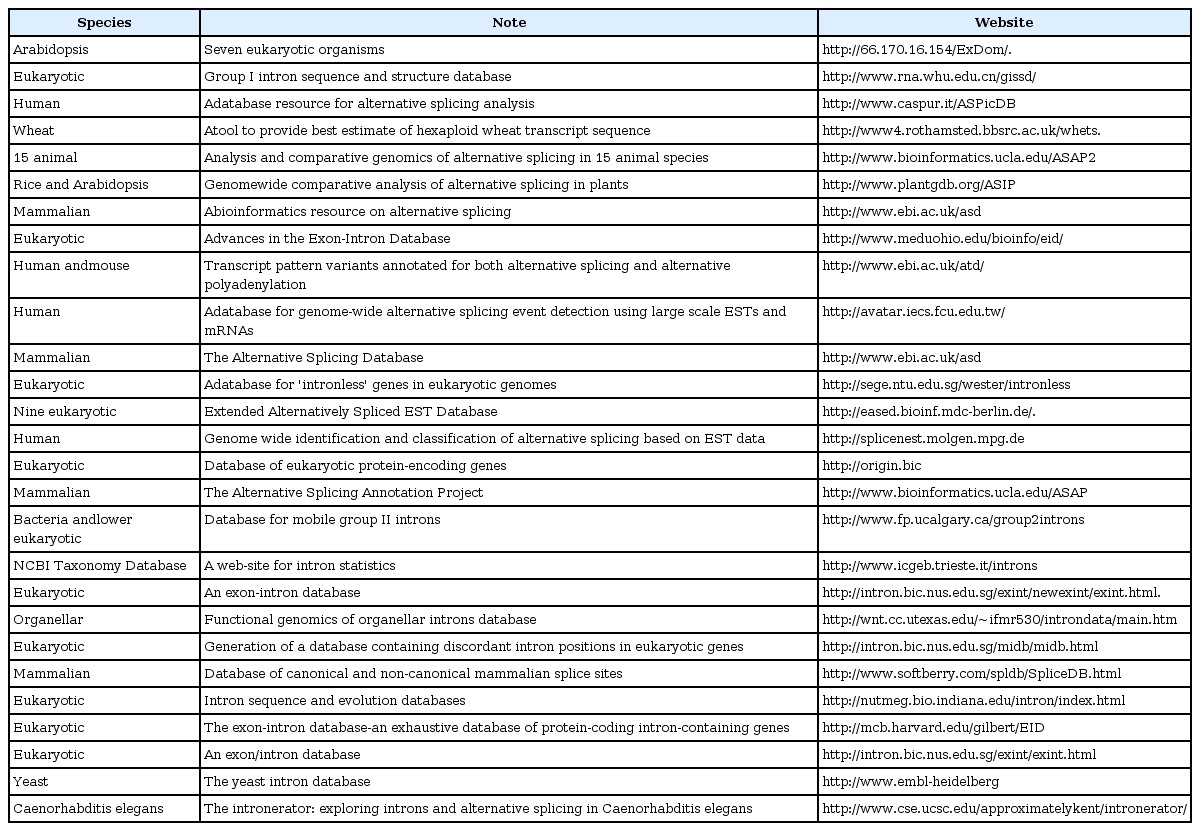

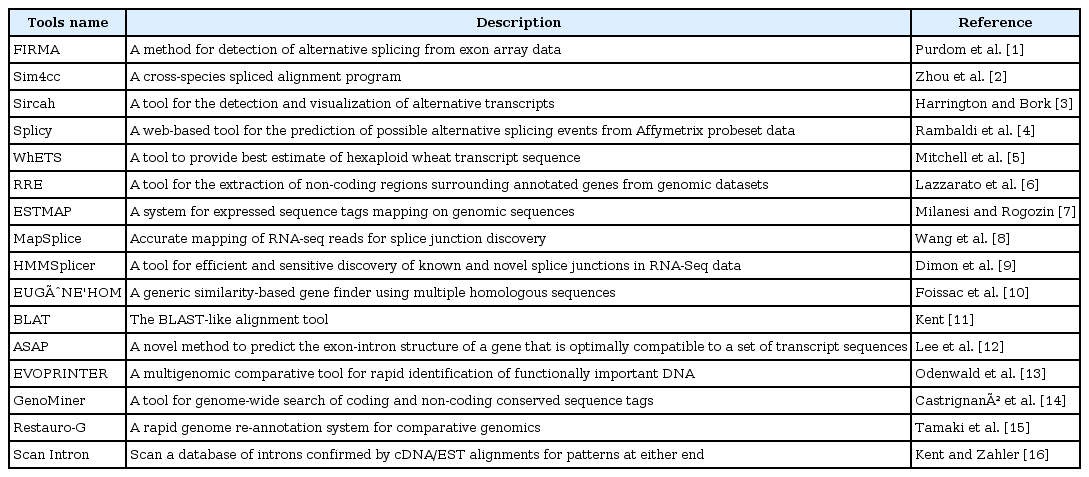

With more and more species' genomes completely sequenced, noncoding sequences have become a focus of researchers' attention, especially for the study of introns. In order to facilitate further research, a number of intron databases have been developed (Table 1). The number of plant intron databases is much smaller than that in mammals and only in several model plants (such as Arabidopsis and rice). Using known genome sequences and coding sequences (expressed sequence tags [ESTs] or cDNA), introns can be detected by aligning coding sequences with genome sequences. Many tools were developed to detect introns in eukaryotes (Table 2) [1-16]. These tools used different algorithms and computer languages (such as Java, C++, and Python) to predict introns.

Therefore, the question is: there are many intron databases, algorithms, and detection methods for the study of eukaryotes, but which among them are the most suitable for the detection of plant introns? Among these tools, the Blast-Like Alignment Tool (BLAT) and Sim4cc are the most commonly used tools. BLAT applies in genomewide alignment [11]. Sim4cc is a tool for aligning cDNA and genomic sequences between species at various evolutionary distances [2]. Rice and Arabidopsis, as monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous model plants, are widespread with regard to in-depth research. Their genome sequences have been annotated in detail, including their gene sequences, complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences, coding DNA sequence (CDS) sequences, exon sequences, intron sequences, and intergene sequences. Therefore, it is possible to use this model plant information to test these intron prediction tools.

Genome annotation is a difficult and accurate project-even the best-annotated or most carefully studied genomes are continually re-released; e.g., release 7 of the Rice Genome Annotation Project was available on October 31, 2011 (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/). But, determining the accuracy and detecting the inherent errors of the genome annotation is a problem. Since introns are removed from protein-coding transcripts, intron lengths are not expected to respect coding frames across the genome [17]. Using intron length distributions, Roy and Penny [18] point out a rapid and simple method for detecting a variety of possible systematic biases in gene prediction or even problems with genome assemblies. Roy's method showed that a good genome annotation is accepted as roughly equal proportions of intron lengths of three phases: a multiple of three bases (3n), one more than a multiple of three bases (3n + 1), and two more (3n + 2). Skewed predicted intron length distributions thus suggest systematic errors in intron prediction. But, many plants with sequenced genomes have not been commented on.

In this study, we compared the advantages and disadvantages of BLAT and Sim4cc for model plants' intron predictions, and we attempted to find a better way to predict the intron information of plants. Based on Roy's method, we evaluated the intron information of 10 plant genomes and discuss a skew in genome wide intron length distributions that indicates systematic problems with intron predictions.

Methods

Genome sequences

Ten plant genome sequences and transcript (EST, CDS, or cDNA) sequences were downloaded and indicated in Table 3 [19-27]. Table 3 contains the name of the 10 plant species, source websites, and genome sequence versions used in this study.

Comparative BLAT and Sim4cc analysis

Using cDNA sequences and gene sequences, we searched rice and Arabidopsis introns by two methods-BLAT and Sim4cc- and then compared the results with annotated information.

The steps of this method are as follows (Fig. 1): 1) Using the gene sequences of BLAT with its own cDNA sequences, we found intron information from the BLAT results by Perl script. 2) We sliced gene sequences and cDNA sequences to folders by Perl script. In these folders, there was one sequence per file, and the gene name was the file name. Using the same gene name of the gene and cDNA file, we blasted the gene sequences and cDNA sequences using Sim4cc. Then, we got intron information from the Sim4cc results by Perl script. 3) We compared the results of the two types of software (BLAT and Sim4cc) and then got the annotated intron information. 4) We aligned intron sequences with their own gene sequences to develop detailed intron information, such as the intron position in the gene, intron length, intron number, forward-exon length, and backward-exon length, etc. 5) We compared the results from the two types of software with the annotated information to validate the methods.

Flowchart of a comparison of BLAT and Sim4cc results in predicting introns. Intron information, including the following information of one intron: gene name, intron number, intron position in the gene, intron length, intron position in the genome, forward-exon length, backward-exon length, and intron sequences. BLAT, Blast-Like Alignment Tool.

Intron length distributions analysis

Using Perl script, we extracted the intron information of the 10 plant genomes from the genome annotation. Then, we counted the number and percentage of 3n, 3n + 1, and 3n + 2 of these 10 plants' intron length distributions.

Results and Discussion

A comparison of BLAT and Sim4cc

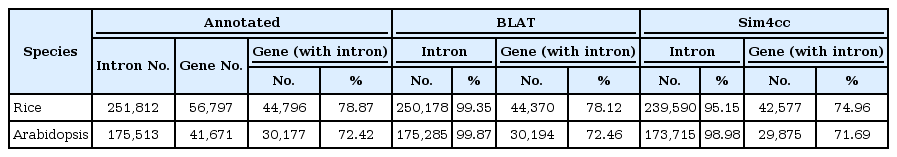

As a prerequisite, it was assumed that the intron annotated information was correct and complete. Then, the software's results were compared with the annotated information. Three sets of results of intron information were obtained: two sets from the software (BLAT and Sim4cc) and one set from the annotated information (Table 4).

Using BLAT, we found 99.35% and 99.87% of the introns of all rice and Arabidopsis annotated introns, respectively. These introns were almost all of the introns in the genome - that is, only 0.13% to 0.65% of the introns were not found. In contrast, by using Sim4cc, 95.15% to 98.98% of the introns were found (1.02% to 4.85% of the introns were lost) of all rice and Arabidopsis annotated introns. In summary, BLAT got more of the introns in a genome than Sim4cc. In light of this result, it seems as though that BLAT produces better results than Sim4cc.

We found 30,194 rice genes with at least one intron by BLAT, but the number was 30,177 according to the annotated information. Because the BLAT results were larger than the annotated results, the BLAT results must have predicted some new and different genes with introns. In the BLAT results, many short-length introns (less than 50 bp) were predicted, but in fact, these short-length introns were part of transcript sequences and were not real intron sequences. In contrast, Sim4cc detected 29,875 genes with introns, and all of these genes were contained in the annotation information. The predicted intron accuracy rate of Sim4cc was 100%. On accuracy, Sim4cc was better than BLAT.

If Sim4cc is used, the user has to splice a whole genome file to many files: one gene, one file. The computing process of Sim4cc was more complex than that of BLAT, and each time, Sim4cc only calculated one cDNA sequence to one gene sequence; so, the executing efficiency and speed are not high. In comparison, BLAT was easier and faster than Sim4cc.

In conclusion, BLAT and Sim4cc can be used to predict introns, but each of them has its advantages and disadvantages. The comparative results are summarized in Table 5. Sim4cc was a cross-species spliced alignment program. In our study, Sim4cc was used to find introns by comparing cDNA sequences and gene sequences. The correct intron can be obtained by comparing one cDNA sequence with its own gene sequence. But, a lot of introns were lost by Sim4cc. In other words, Sim4cc was good at detecting the correct intron but not at predicting the whole number of introns in a genome. In contrast, BLAT can predict most of the introns - nearly all of the total introns in a genome. But, there were some false-positive predictions of introns. However, the proportion of this error was very small. As a result, BLAT will be proposed to annotate plant genome introns.

Intron length distribution of 10 plants

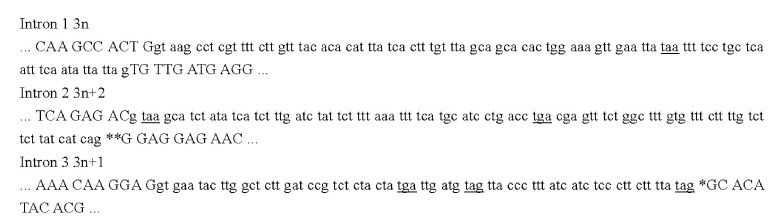

According to Roy's method, many predicted introns in the plant genomes had in-frame stop codons, and the predicted introns in these genomes were equally as likely to be a multiple of 3 bp (3n) as to contain a plus one (3n + 1) or two (3n + 2) bp. Here was an example of three phases from an Arabidopsis thaliana gene, AT1G17600.1 (Fig. 2).

An example of three phases of intron from an Arabidopsis gene, AT1G17600.1. Upper/lowercase sequence indicates exon/intron sequence. Asterisks indicate frameshifts introduced by non-3n introns; intronic in-frame stop codons are underlined. Intron 1 is a 99-bp intron (3n) with one in-frame stop codon. Intron 2 is a 100-bp intron (3n + 2), which has two in-frame stop codons and thus does not interrupt the open reading frame. Intron 3 is a 74-bp intron (3n + 1) with three stop codons.

By analyzing genome sequence annotations, we got three-phase intron distributions for 10 plant species (Table 6). If the plant intron annotation is more accurate, the number of three phases should be similar (one-third each). For 80% (8/10) of species, there were similar numbers of the three phases. It should be noted that most of these plant species annotations were the best annotations to date, but new annotations will be continually released to correct errors and false-positive results.

Two-species 3n intron skew analysis

For all of the 10 genomes (Table 6), there were very similar numbers of 3n + 1 and 3n + 2 introns, and the percentages of 3n + 1 and 3n + 2 introns were within 0.8%. In contrast, the number of 3n introns varied much more widely, from 29.1% to 47.7%. In this study, two species' genome introns showed strongly skewed percentages, in that the 3n intron percentage was much lower or higher than the expected value (one-third). Such a skew suggests systematic errors in the intron prediction.

The green alga Ostreococcus lucimarinus has one of the highest gene densities known in eukaryotes, with many introns [28]. There was a striking excess of predicted 3n introns (47.7% of all predicted introns, 1,130) compared to 3n + 1 (25.8%, 611) and 3n + 2 (26.5%, 628) introns. In this case, many predicted 3n introns were not true introns but instead exons.

The unicellular green alga Ostreococcus tauri is the world's smallest free-living eukaryote known to date [29]. These predicted introns showed a deficit of 3n introns (29.1%, 1,262), much lower than 3n + 1 (35.8%, 1,553) and 3n + 2 (35%, 1,519) introns. This result is very close to previous studies [18]. In this case, 3n introns may be mistakenly regarded as coding sequences, whereas a 3n + 1 or 3n + 2 intron may be inferred from the disruption of the coding frame.

Concluding remarks

By comparing the advantages and disadvantages of BLAT and Sim4cc in intron prediction, we found that BLAT is faster and can predict more introns than Sim4cc. Through using intron length distribution to detect introns' annotations, it is a simple and fast method for detecting a variety of possible systematic biases in intron prediction or even for detecting problems with genome assemblies.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30900780), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 20090461260 & No. 201104647), and the Postdoctoral Foundation of Shandong Agricultural University (No. 76267).