Application of Whole Exome Sequencing to Identify Disease-Causing Variants in Inherited Human Diseases

Article information

Abstract

The recent advent of next-generation sequencing technologies has dramatically changed the nature of biomedical research. Human genetics is no exception-it has never been easier to interrogate human patient genomes at the nucleotide level to identify disease-associated variants. To further facilitate the efficiency of this approach, whole exome sequencing (WES) was first developed in 2009. Over the past three years, multiple groups have demonstrated the power of WES through robust disease-associated variant discoveries across a diverse spectrum of human diseases. Here, we review the application of WES to different types of inherited human diseases and discuss analytical challenges and possible solutions, with the aim of providing a practical guide for the effective use of this technology.

Introduction

Whole exome sequencing (WES) is a technique to selectively capture and sequence the coding regions of all annotated protein-coding genes. Coupled with next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, it enables the analysis of functional regions of the human genome with unprecedented efficiency. Since its first reported application [1, 2], WES has emerged as a powerful and popular tool for researchers elucidating genetic variants underlying human diseases (Fig. 1) despite certain limitations (see below).

Overview of WES Pipeline

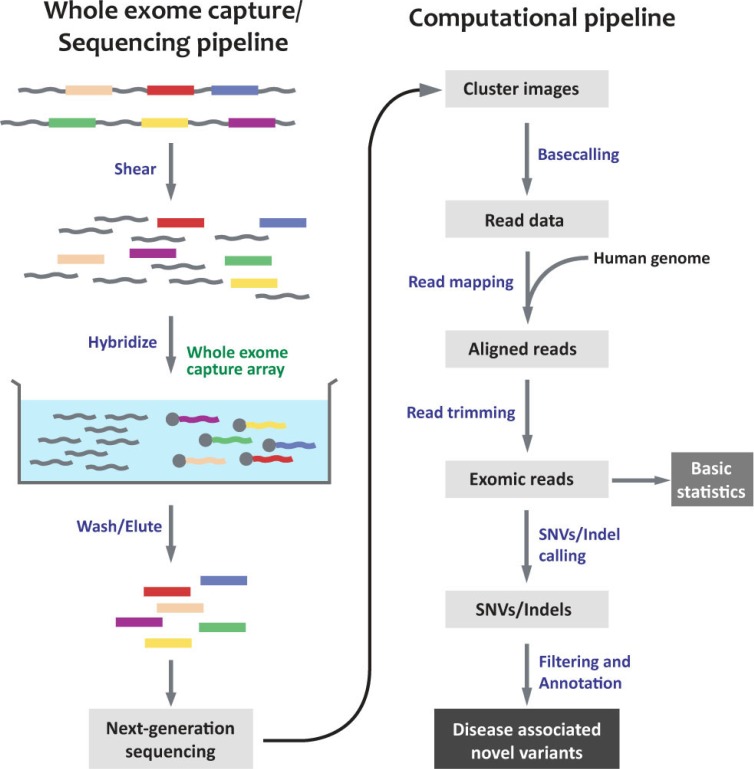

WES pipelines generally follow a similar process, regardless of the capture method and NGS platform used, as summarized in Fig. 2. The experimental pipeline can be divided into two parts: 1) preparing genomic DNA libraries and hybridizing them to capture arrays and 2) NGS of the eluted target fragments. There are a number of commercially available capture arrays, and their strengths and weaknesses have been well described elsewhere [3]. Once short sequencing reads have been generated, they are mapped to the reference human genome, and variant calling is carried out. Subsequent annotation of these variants is necessary to further evaluate their potential biological effect; publicly available software and databases can be used for this purpose.

Strengths and Weaknesses of WES

WES is a robust technology that is extremely practical for investigating coding variation at the genome-wide level. Despite the plummeting cost of sequencing in the past few years, WES at mean coverage depth of 100× still costs five times less than whole genome sequencing (WGS) at mean coverage depth 30×. In addition, the size of WES data per patient is approximately a sixth of WGS data, resulting in reduced processing time and imposing less of a burden in terms of data storage.

However, it is important to understand the limitations of WES technology. Certain protein-coding regions might not be covered due to incomplete annotation of the human genome. Further, WES does not cover potentially functional non-coding elements, including untranslated regions, enhancers, and long-noncoding RNAs, although these are, in themselves, not clearly defined. Another drawback to WES is the limited ability to detect structural variations, such as copy-number variations, translocations, and inversions.

In spite of these limitations, WES is still the tool of choice for many researchers-its practical advantages allow large numbers of patients to be screened in a robust fashion, a crucial aspect of mutation discovery in human genetics research.

Application of WES to Various Human Disease Types

WES has been used in identifying genetic variants associated with a variety of diseases. Here, we discuss different categories of inherited human disease and the methodology employed to examine each case.

Mendelian Diseases, Recessive

Diseases inherited in a recessive pattern have traditionally been highly amenable to genetic analysis, due to the fact that homozygous variants are easily detectable. Previously, if a large family with many affected members was available for pedigree analysis, one would perform linkage analysis by genotyping family members in order to identify relatively short genomic intervals that presumably contained the disease-associated variant. Direct interrogation of entire genomes for homozygous variants is now possible with NGS technologies, and public datasets can be used to exclude common variants that are less probable to be disease-causing. Identifying recessive variants is especially straightforward if the proband is a product of a consanguineous marriage-sequencing the entire exome of the patient would likely yield a manageable number of rare homozygous variants, and further studies could be performed to investigate the functional relevance of these variants.

In one of the earliest reports of the application of WES technology, Bilgüvar et al. [4] identified recessive mutations in WDR62 in multiple Turkish consanguineous patients with severe developmental brain defects. Very little was known about WDR62 at that time, but subsequent genetic and functional studies have since validated the importance of this gene in proper brain development. More recently, a large cohort of patients of similar genetic status and clinical manifestation were analyzed using homozygosity mapping from WES data [5]. The authors uncovered 22 genes not previously identified as disease-causing, further demonstrating the power of WES as an ideal tool for gene discovery.

Mendelian Diseases, Dominant

Mendelian diseases with dominant modes of inheritance pose greater technical challenges for genetic analysis. Heterozygous variants are generally more difficult to detect and analyze, not only due to their sheer number as compared to homozygous variants but also because they are subjected to higher false positive and false negative errors. Nevertheless, one could still design one of the following experiments to elucidate the genetic architecture underlying these diseases, depending on the availability of patient cohorts and the effect of the disease on reproductive fitness.

Familial cohort

If large families with the disease of interest are available, WES should be performed on at least two affected family members. In analyzing the results, any shared variants could potentially be disease-causing; using linkage data to focus on the variants located in linked intervals would greatly reduce the number of variants to be considered. A recent example of such an approach is a WES study on familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (FALS) [6]. The authors recruited two large families with FALS and selected two affected members with the greatest genetic distance from each family for WES. Among the rare functional variants that were identified, they tested the shared variants for Mendelian segregation among affected family members, eventually narrowing their search down to a single common gene, PFN1.

Non-familial cohort

When large families with the disease are not readily available, one could perform WES on a number of unrelated patients with similar clinical manifestations and select genes that are commonly mutated in the patient cohort. In carrying out such an experiment, it is important to consider the background mutation burden of the entire human gene set; it is possible that the longest genes might contain the highest number of rare functional variants and therefore appear to be the most interesting. To circumvent such errors in analysis, the variant burden of each gene should be normalized using data from a control population. In a WES study of pseudohypoaldosteronism type II (PHAII), the variant burden of every gene from 11 unrelated patients was compared against that of 699 controls [7]. A single gene that was specifically enriched for mutations in the patient set, KLHL3, was identified (5 variants from 11 patients compared to 2 from 699 controls, with p-value of 1.1 × 10-8).

Non-inheritable diseases

If the disease phenotype is severe enough such that it affects reproductive fitness, one could hypothesize that de novo variants-variants that emerged during meiosis of the germ cells that are unique to the offspring-are directly associated with the disease. These can be detected by performing trio-based WES on the unaffected parents and the proband, and variants that are present in the offspring only and not in the parents will be called de novo variants. The rate of de novo mutations has been shown to be relatively stable and affected primarily by paternal age [8]. WES of family quartets can also be carried out, where unaffected siblings are recruited simultaneously and their de novo mutations are compared against those of the proband. A series of studies involving autism trios and quartets recently demonstrated that rare de novo mutations were associated with the risk of autism and identified multiple de novo mutations in SCN2A, KATNAL2, and CHD8, implicating these genes in the genetic etiology underlying autism [9-11].

Common Complex Diseases

The majority of the disease burden that modern societies endure can be attributed to common complex diseases. These diseases typically have both genetic and environmental causes, and they also possess significant genetic heterogeneity, making the identification of disease-causing genes very challenging. Traditionally, the use of linkage analysis of families with extreme disease phenotypes has been somewhat successful in mutation discovery [12]. However, these mutations are particular to patients with extreme phenotypes and do not explain the pathophysiology of disease for patients in the general population. Large genome-wide association studies of common variants have also been employed with limited success; the findings in many studies are not robust and only explain a small fraction of the disease risk [13]. As a result, greater attention has been drawn to profiling rare variants with allele frequencies of less than 1% in complex diseases.

Taking advantage of WES technology, several large-scale projects have been launched. One such example is a project led by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to discover novel genes underlying cardiovascular disorders. As a result of sequencing the exomes of 2,440 individuals, the study reported an excess of rare functional variants and concluded that large numbers of subjects will be required to attain sufficient power to discover variants that are significantly associated with the disease traits [14].

Challenges in Analysis

WES yields extensive lists of genomic variation, and there are many important caveats to bear in mind when carrying out analysis of such data. In this section, we address the potential challenges that the investigators need to consider when designing or performing the experiments.

False Positive and False Negative Calls

Recent improvements of the WES technique in both experimental and bioinformatics pipelines have reduced the occurrence of false positive (false variant that is called true) and false negative (true variant that is failed to be called) variant calls substantially. Currently, we can achieve ~98% sensitivity and 99.8% specificity from exome sequencing data, minimizing the chance of missing any true variants as compared to the analysis of SNP array data (data not shown). However, as mentioned previously, it is technically challenging to detect and evaluate rare heterozygous variants because heterozygous variant calling is more susceptible to the technical errors and require higher read depth. For example, at a coverage depth of 4× (i.e., if a base is covered by 4 independent reads) and assuming a 1% per-base error rate, a homozygous variant will be called if 0 and 4 reads are observed for the reference and nonreference alleles respectively, with a false positive rate of 2 × 10-4. However, if both reference and nonreference alleles have 2× coverage, a heterozygous variant will be called with a false positive rate of 0.34. This presents a particular problem when one considers the uneven coverage in WES resulting from differential capture efficiencies across the exome. To achieve reliable heterozygous calling, it is therefore necessary to achieve sufficient coverage depth across the entire exome so as to minimize the number of bases with low coverage.

Another challenge to analysis is read misalignments; the typical length of NGS reads is near or less than 100 bp, and even paired reads are subject to being improperly aligned, because there are large portions of the human genome where the DNA sequence is highly repetitive and duplicated. In fact, segmental duplicated regions, defined as intervals larger than 1 kb having a homology >90% with other parts of the genome, encompass about 5% of the human genome [15]. Hence, imposing more rigorous filtering criteria to remove such reads, including Phred score and mapping quality score cutoffs, is essential.

Population Stratification

The recent, dramatic acceleration in human population growth over the last several millennia has resulted in an excess of rare variants in the human genome, and these variants have not had enough time to be subjected to natural selection [14]. Since the identification of disease-associated variants consists largely of assessing rare variants, one must bear in mind the possibility that a variant of interest could be population-specific and not necessarily disease-causing. This is especially problematic if the patient cohort is not of European or, more specifically, northwestern European descent. Recent public sequencing projects, such as the 1000 Genomes Project and NHLBI Go Exome Sequencing Project, have covered a greater variety of non-European ethnic groups than before, and they report that these groups harbor a greater burden of rare variants as compared to Europeans [14, 16]. For example, indigenous African individuals may carry 2-3 times more rare variants, and East Asian individuals may carry 1.5 times more variants when compared to individuals of European descent. Rare variants specific to the population of study might be easily mistaken as patient-enriched variants; it is thus necessary to screen the presumed variant with carefully matched healthy individuals.

Locus Heterogeneity

Locus heterogeneity describes the phenomenon where a single disease can be caused by multiple different loci across different patients. Over the last few decades, studies performing linkage analysis followed by positional cloning have identified many genes as being responsible for various inherited diseases; the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database currently records 3,000 genes as being disease-causing (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim). This also suggests that the majority of the remaining diseases without known associations with genes have not been amenable to classical approaches and will likely display extensive genetic heterogeneity. Increasing the size of the patient cohort will increase the power to discover variants, as shown in Fig. 3. Pathway or gene ontology analyses can also be performed to link the mutated genes into certain functional categories-there are several publicly available tools for this purpose. A good example of this method is the aforementioned study on PHAII-the authors initially identified KLHL3 from WES of 11 patients and subsequently considered KLHL3's presumed functional partner, CUL3, as a potential gene candidate. Extending the screening to 52 patients, KLHL3 was found to be mutated in 24 patients (46.2%) and CUL3 in another 17 patients (32.7%), explaining a total of 78.8% of the entire patient set. Another possible approach is to re-evaluate the clinical diagnosis of patients in the cohort by correlating subtle differences of clinical measurements and genetic variants in order to focus the analysis on a more clinically homogeneous set of patients as a separate cohort.

Increased sensitivity to detect causal gene as patient cohort size increases. Percentages shown denote ratio of patients that carry rare functional variants. Simulation was performed assuming that 0.1% of healthy controls carry rare functional variants, and was iterated 105 times. Each iteration was evaluated and called 'detected' if the p-value exceeded the genome-wide significance.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that NGS has provided researchers with unprecedented power to resolve the genetic etiology of various human diseases. When WES was first introduced, its utility was highly debated due to its apparent limitations, such as incomplete coverage of functional elements and low sensitivity for structural variant detection. However, the practical advantages of the technology have made it a favored tool for researchers, and WES will likely continue to be widely used for the foreseeable future. Furthermore, as library capture methods and data analysis pipelines improve, increasing amounts of genomic information, aside from single-nucleotide changes and short indels, can be extracted. Examples of this include homozygosity interval mapping, common SNP genotyping information for various population-level analyses, and detection of structural variants [17, 18]. Finally, the strengths of WES-short turnaround times, low cost, and relatively easy data interpretation-make it an optimal tool for clinical diagnosis. The increased use of WES in the clinic will surely spur the development of personalized medicine and reinvent treatment practices in the near future [1, 19].

Acknowledgments

This work is in part supported by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore (to G.G.) and a NHLBI grant K99HL111340 (to M.C.).