Introduction

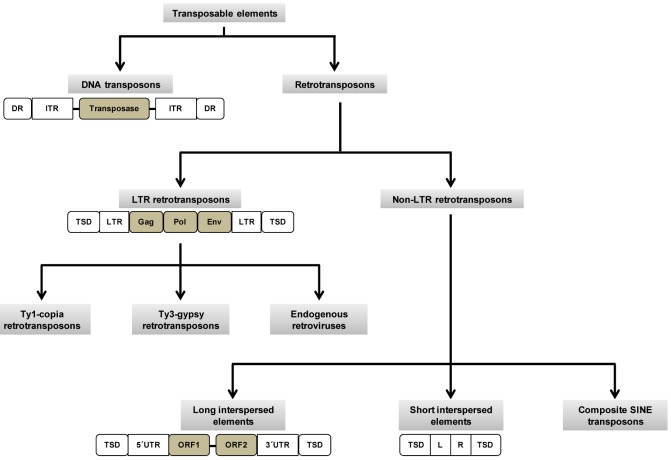

Transposable elements (TEs) are DNA sequences that are capable of integrating into the genome at a new site within the cell of its origin. Sometimes, the change in their positions creates or reverses mutations, thereby altering the cell's genotype. Barbara McClintock's discovery of these "jumping genes" earned her a Nobel Prize in 1983 [1]. TEs are prevalent in all plants and animals. In mammals, TEs and their remnants make up almost half of the genome, and in some plants, they constitute up to 90% of the genome [2]. TEs consist of two major classes: DNA transposons and retrotransposons. DNA transposons are capable of moving and inserting into new genomic sites [3]. Although they are currently not mobile in the human genome, they were active during early primate evolution until ~37 million years ago (Mya) [4]. Retrotransposons replicate by forming RNA intermediates, which are then reverse-transcribed to make DNA sequences and inserted into new genomic locations [4]. Based on the presence of long terminal repeats (LTRs), retrotransposons are further classified into two groups: LTR and non-LTR transposons. In humans, LTR elements are called human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs). It is estimated that HERVs inserted into the human genome >25 Mya [5, 6]. Non-LTR retrotransposons include long interspersed element 1 (LINE-1 or L1), Alu, and SVA elements. Studies have revealed that these are the only TEs that are currently active in humans [7, 8, 9, 10, 11].

TEs have driven genome evolution in multiple ways. Retrotransposons comprise a large proportion of the genome, especially in plants and mammals. The effect of the increase in retrotransposons has been tolerated during evolution. Accumulating literature has proven that mobile elements are useful tools for studying genome evolution and gene function [12]. A comparative analysis has shown that the human genome makes 655 perfect full-length matches with vertebrate TEs. TE insertions have been shown to have many effects, such as regulation of gene expression, increased recombination rate, and unequal crossover. TE insertions have caused many effective changes in the human genome, and the selected changes have been responsible for the evolution of the human lineage [13]. The human genome contains many recently inserted active TEs, such as AluYa5, AluYb8, and AluYc1. Alu elements are a family of primate-specific short interspersed DNA elements. Various studies have proposed that Alu element insertions have created many variants that can potentially be used as DNA markers in human population studies, as well as in forensic analyses. Kass et al. [14] have identified an Alu-based polymorphism that consists of four alleles, from which the evolutionary order can be predicted.

The effects of TEs on genetic instability and human diseases have not been thoroughly studied. The mobile property of TEs is the reason for their mutational potential. TE insertions may create a broad range of effects on humans, ranging from silent mutations to alternative splicing. Both insertions and excisions of TEs can cause genomic instability, thus causing many human diseases, including genetic disorders, psychiatric problems, and cancer [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. Furthermore, TE insertions may result in insertional mutations, non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR), creation of novel regulatory sequences, and epigenetic changes [22]. A large number of human diseases that are associated with NAHR between Alu elements have been reported [22]. Technical advances have helped to detect TE-associated diseases and develop novel biomarkers for clinical diagnostics. Computational tools have been developed to study the dynamics of transposition at a population level, thus providing critical insights into the mechanisms behind genome evolution. Finally, combining the genomic materials from diverse individuals followed by high-throughput sequencing can enhance the significance of characterizing genomic polymorphisms in a population [23].

In this review, we will provide updates on our current understanding of the roles of TEs in genome evolution and genetic instability. Further, we focus on how their activity affects gene expression and causes disease states in human beings.

Role of Retrotransposons in Human Genome Evolution

Brain evolution is an important process that accelerated the evolution of humans. This occurred due to natural selection and genomic variation, a major source of which has been TE insertions. TE insertions contributed markedly to variation and increased the speed of evolution [24, 25, 26]. Furthermore, they increase the recombination rate, in addition to affecting genes and their expression [24, 26]. From an evolutionary perspective, humans are unique in the speed of evolution and the number and activity of TEs. It is proposed that the high frequency of TE insertions is responsible at least in part for the rapid evolution of humans. It is speculated that some sets of genes might have been activated or suppressed due to variations caused by TE insertions, which in turn increased the chances for evolution [13]. There has been a prominent impact of retrotransposons on human evolution at the genomic level. Retrotransposons have shaped human evolution at the RNA level through various mechanisms, such as modulation of gene expression, RNA editing, and epigenetic regulation [27].

LTR retrotransposons

In humans, LTR retrotransposons are called HERVs (Fig. 1), which constitute 5% of the genome. The human genome shows 99% similarity with chimpanzees and bonobos. Hence, the differences between these species are likely to be in regulatory sequences: promoters, enhancers, polyadenylation signals, and transcription factor (TF) binding sites. The LTRs of HERVs help in regulating the expression of nearby genes. The active human-specific LTRs that have been identified belong to the HERV-K family. It is proposed that some of these endogenous retroviruses may have integrated into regulatory regions of the human genome and that they eventually contributed to human evolution [28]. Khodosevich et al. [28] suggested that regulatory sequences found in retroviral LTRs may alter the expression of (or even inactivate) adjacent genes. On the other hand, HERV insertion may benefit the host, for example, by reverting harmful mutation [28].

Non-LTR retrotransposon

Human non-LTR retroposons include both active (L1, Alu, and SVA) and inactive elements (L2 and mammalian-wide interspersed repeat). Although more than 500,000 copies of L1 elements are found in the human genome, only 100 copies are known to be intact [29]. An intact L1 element is approximately 6 kilobases (kb) in length, with a 5' untranslated region (UTR) containing an internal RNA polymerase II promoter, two open reading frames (ORF1 and ORF2), and a 3' UTR (Fig. 1) [29, 30]. L1 elements are the only autonomous TEs in the human genome because of their retrotransposition property, called target-primed reverse transcription [27]. Alu elements are often called "a parasite's parasite," because they do not code for a polymerase and, hence, are non-autonomous in nature. Alu elements depend on L1 elements for retrotransposition machinery [31, 32, 33]. However, they are considered the most successful TEs in the human genome in terms of copy number [27]. An intact SVA element is approximately 2 kb in length, which includes a hexamer repeat, an Alu-like region, a variable number of tandem repeats, and a HERV-K10-like sequence. SVA elements are also non-autonomous and most likely depend on L1 retrotransposition machinery [34, 35].

Two key features of non-LTR retrotransposons that control retrotransposition activity are high copy number and continued activity over millions of years [5, 27]. From an evolutionary perspective, the observed uniqueness of non-LTR retrotransposons is due to their vertical transfer in both primates and mammals [4, 5, 36]. Amplification rates among non-LTR retrotransposons are not uniform (Alu, 40 Mya; L1, 12-40 Mya; SVA, 6 Mya) [27]. Among non-LTR retrotransposons, Alu elements are the most thoroughly studied in relation to evolution. Alu repeats may cause genomic diversity in various ways. Their amplification has enabled them to become the largest family of mobile elements in the human genome. It is estimated that thousands of Alu elements have integrated into the human genome since the divergence of humans and African apes [37, 38, 39, 40]. Although some Alu insertions have caused harmful mutations, most have contributed to genetic diversity [8]. Moreover, Alu repeats have also influenced the accumulation of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the genome [30, 40, 41]. From previous reports, it is evident that most of the recent Alu insertions are the source of genetic variations, which have been useful for studying both the relationships between populations and the evolution and organization of tandem-arrayed gene families [37, 38, 39, 40]. Batzer and Deninger [42] suggested that the Alu insertion, in relation to genetic variation, may also be useful in generating species-specific genetic markers.

Roles of TEs in Genomic Instability and Disease States

TEs can cause genomic instability either by insertions or by rearrangements in the genome. Notably, structural variations in the human genome are the primary cause of inter-individual variability. Structural variations include insertion, deletion, inversion, duplication, and translocation. The characteristics of TEs, such as abundance in the genome, high sequence identity, and ability to move, make them major contributors to genomic instability [5, 27, 43]. Recent studies have revealed the implications of TEs in genomic instability and human genome evolution [44]. Mutations associated with TE insertions are well studied, and approximately 0.3% of all mutations are caused by retrotransposon insertions [27]. Such insertions can be deleterious by disrupting the regulatory sequences of a gene. When a TE inserts within an exon, it may change the ORF, such that it codes for an aberrant peptide, or it may even cause missense or nonsense mutations. On the other hand, if it is inserted into an intronic region, it may cause an alternative splicing event by introducing novel splice sites, disrupting the canonical splice site, or introducing a polyadenylation signal [8, 9, 10, 11, 42, 43]. In some instances, TE insertion into intronic regions can cause mRNA destabilization, thereby reducing gene expression [45]. Similarly, some studies have suggested that TE insertion into the 5' or 3' region of a gene may alter its expression [46, 47, 48]. Thus, such a change in gene expression may, in turn, change the equilibrium of regulatory networks and result in disease conditions (reviewed in Konkel and Batzer [43]).

The currently active non-LTR transposons, L1, SVA, and Alu, are reported to be the causative factors of many genetic disorders, such as hemophilia, Apert syndrome, familial hypercholesterolemia, and colon and breast cancer (Table 1) [8, 10, 11, 27]. Among the reported TE-mediated genetic disorders, X-linked diseases are more abundant than autosomal diseases [11, 27, 45], most of which are caused by L1 insertions. However, the phenomenon behind L1 and X-linked genetic disorders has not yet been revealed. The breast cancer 2 (BRCA2) gene, associated with breast and ovarian cancers, has been reported to be disrupted by multiple non-LTR TE insertions [9, 18, 49]. There are some reports that the same location of a gene may undergo multiple insertions (e.g., Alu and L1 insertions in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene) (Table 1).

It has also been proposed that inverted repeats are likely to be hotspots of genomic instability [50]. Closely occurring Alu repeats form hairpin structures that are prone to double-strand breaks (DSBs) and excision [50, 51]. In addition, de novo Alu insertions may create new inverted repeats that result in rearrangements in future generations [43]. Due to the abundance of TEs in the human genome, the probability of TE-mediated NAHR translocations is high. Kolomietz et al. [52] reported that Alu elements are often found in and around the breakage points of translocations and result in diseases [53]. Some studies have analyzed the human genome using the chimpanzee reference genome and found that deletions that are caused by Alu-mediated NAHRs are 9 times more frequent than L1-mediated NAHRs in the human genome [54, 55]. Alu-mediated NAHRs are known to be associated with various genetic disorders and cancer (Table 1) [8, 10]. L1 endonuclease creates abundant DSBs that are required for retrotransposition in mammalian cells and eventually contribute to genomic instability [56]. However, it has been difficult to define this in an experimental condition, as physiological conditions cannot be simulated in vitro. Moreover, it is also difficult to distinguish DSBs caused by L1 from DSBs caused by other mechanisms in vivo [44, 56].

From recent studies, it is apparent that the methylation state of DNA is associated with cancer [57]. TEs-in particular, the promoters of L1 elements-are reported to be demethylated in cancer cells [58, 59]. On the other hand, the methylation of retrotransposons is supposed to be a defense mechanism against retrotransposition in somatic cells [60]. It has also been reported by some studies that the L1 transcription rate is increased in hypomethylated cancer cells [58, 61]. Demethylation of TE promoters may result in their activation, which in turn could modify the TF level in the cell. It is possible that such changes in TF levels lead to alterations in global gene expression [57]. In addition, demethylation may result in the activation of the L1 antisense promoter, which may eventually produce cancerassociated chimeric transcripts [62, 63].

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Taken together, the mechanisms discussed above have demonstrated the considerable impact of TEs on human genome evolution, genetic instability, and disease occurrence. There has been a recent increase in studies demonstrating the roles of TEs in multiple molecular processes. Importantly, several studies have found an association between TEs and cancer conditions. Technological developments have led to promising techniques (e.g., next-generation sequencing) that will assist researchers in studying, understanding, and confirming the role of TEs in genetic instability and diseases. Such progress may lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies in the near future, such as personalized gene therapy for the treatment of genetic disorders. The clinical community has already realized the importance of personalized cancer treatments and is moving toward excellence in such treatment strategies. Therefore, we believe that in-depth studies on the role(s) of TEs in evolution, the epigenetic control of gene expression, and clinical aspects will be of paramount importance in uncovering novel mechanisms that can be targeted for therapeutic intervention.