|

|

- Search

| Genomics Inform > Volume 12(4); 2014 > Article |

Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are known for their role in mRNA silencing via interference pathways. Repetitive elements (REs) share several characteristics with endogenous precursor miRNAs. In this study, 406 previously identified and 1,494 novel RE-derived miRNAs were sorted from the GENCODE v.19 database using the RepeatMasker program. They were divided into six major types, based on their genomic structure. More novel RE-derived miRNAs were confirmed than identified as RE-derived miRNAs. In conclusion, many miRNAs have not yet been identified, most of which are derived from REs.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs of ~22 nucleotides (nt) in length and are single-stranded in their mature form. Primary miRNAs are expressed from genomic regions and processed to generate precursor miRNAs by Drosha [1]. Precursor miRNAs have a hairpin structure; therefore, their sources (or, the genomic loci from which they originate) have a palindromic structure [2]. The precursor miRNAs are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and processed into a duplex by Dicer, one of which is preferentially loaded into Argonaute (AGO) [1, 3]. Mature miRNAs function via the RNA-induced silencing complex and AGO protein-mediated binding to the target mRNA by complementary base pairing to the 3' untranslated region [4].

Repetitive elements (REs) are interspersed throughout the genome, and they increase genomic instability through various mechanisms. REs consist of transposable elements (TEs) and tandem repeats (e.g., satellite DNA, simple repeat DNA). REs can directly impact coding sequences or other functional sequences in the host genome as follows. They can affect transcription by acting as alternative promoters [5, 6, 7], forming structural isoforms through alternative exons, and by providing polyadenylation signal sites important in transcriptional termination [8]. REs are also important for inhibiting gene expression at the post-transcriptional level by producing miRNA sequences [2, 9]. REs comprise paralogous miRNA gene families and speciesspecific miRNA gene families [10]. Some miRNAs originate from unique genomic sequences, and others originate from REs. Recently, the association of REs with miRNAs was established in several studies that demonstrated connections between miRNAs and TEs [9, 11, 12]. These studies suggest that REs are important for miRNA origin, expression, and regulatory network formation [2, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. Especially, some REs have a palindrome structure, and these sequences have great potential to make a precursor miRNA form. In previous studies, miniature inverted TE (MITE)-derived miRNAs were identified in the human genome [2]. As one of the REs, medium reiterated sequences (MERs) have a palindrome structure in the mammalian genome [17]. MERs were also predicted to make miRNAs [10], and MER-derived miRNAs were confirmed in experiments in human cell lines [11]. REs are ubiquitous and scattered throughout the host genome in abundant numbers; therefore, these RE families have the possibility of making paralogous miRNAs. A MITE-derived miRNA, miR-548, has many homologous gene families [18], and a MER-derived miRNA, miR-1302, also has many homologous miRNAs in the human genome [10]. Likewise, the long interspersed elements (LINE) element also makes an miRNA precursor form by "tail to tail" method [12]. In the case of hsa-miR-28, two LINE elements are oppositely oriented and then make one miRNA precursor form [15]. Based on these results, we separated miRNAs in the case of two REs making one miRNA and of a palindrome structure RE making one miRNA.

REs prefer rapid evolution compared to other genomic sequences; RE-derived miRNAs have a tendency to make phylogeny-specific miRNAs [9]. In this respect, primate-specific Alu-derived miRNAs are primate-specific, and MITE-derived miR-548 was mainly discovered in primates [18]. Genomic duplication events, such as segmental duplications or tandem duplications, also create REs and RE-derived miRNAs in animals [19, 20]. Therefore, many RE-derived miRNAs were identified in the human, rhesus, and mouse genomes [20]. In the plant genome, TE insertions can make both siRNAs and miRNAs, and MITEs have an important role in the creation and evolution of novel miRNAs [13]. In this respect, to analyze TE-overlapping patterns and abundant overlapping TEs with miRNAs in the human genome can provide evolutionary clues in further studies.

In the miRBase database, 55 experimentally validated human miRNA genes derived from TEs are described, and 85 novel miRNAs are predicted from the potential conserved secondary structures of 587 human TEs [9]. However, these studies concentrated exclusively on the identification of miRNAs containing REs and did not analyze the patterns of overlap between REs and miRNAs. Moreover, newly identified miRNAs and small transcripts with the potential to form miRNAs have not been considered. Therefore, we analyzed TEs that overlapped with both previously identified and novel miRNAs and examined six patterns of overlap that occur. Our results suggest that REs contribute to the production of human miRNA genes by a number of mechanisms.

We used miRNAs annotated as small non-coding RNA genes defined by the GENCODE database, v.19 (http://www.gencodegenes.org) [21]. RepeatMasker outputs (hg19 assembly, RM v.330, repbase libraries 20120124) were obtained from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/, hg19). To analyze the intersection between miRNA and REs, we used the intersectBed command (with options -wa and -wb) in BEDTools [22].

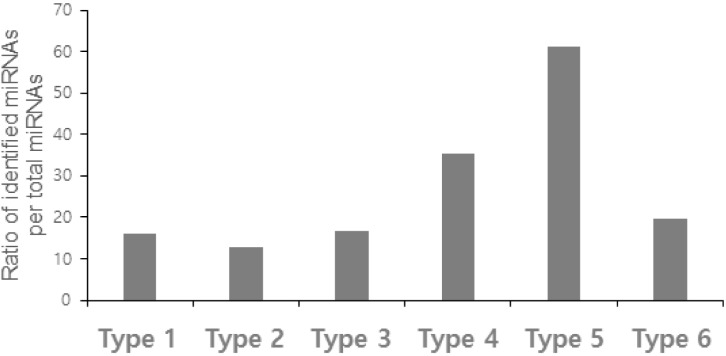

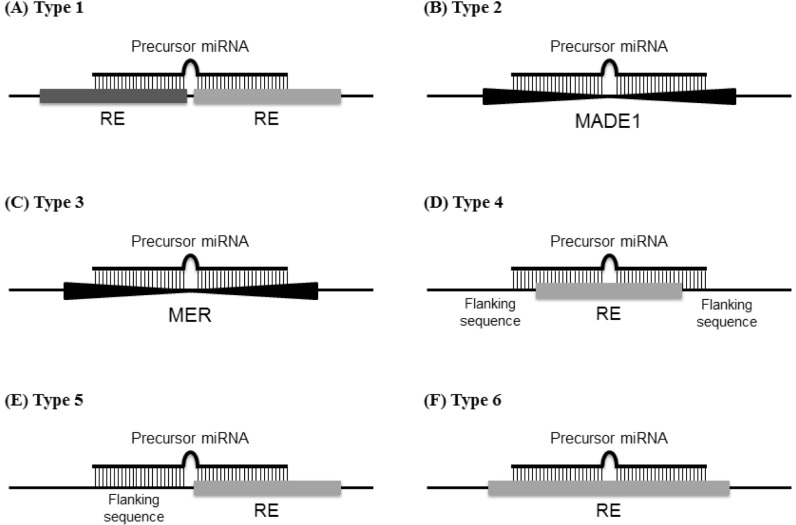

The RE-matched precursor miRNA sequences obtained were divided into six major types. The six types were as follows: miRNAs that overlapped with two or more REs (type 1), miRNAs related to the TcMar-Mariner family (type 2) and the MER family (type 3), and miRNAs sorted according to the matching scheme between REs and miRNAs (type 4 to type 6). The classification scheme is described in a flow chart (Supplementary Fig. 1). miRNA sorting and deletion of duplications were performed using Microsoft Excel (Supplementary Table 1).

In total, 1,900 miRNAs were confirmed as RE-originated, including 406 previously identified miRNAs and 1,494 novel miRNAs (Table 1). We identified 452 type 1 miRNAs, which have two or more RE-derived precursor miRNAs (23.79%) (Fig. 1A). Only 72 previously identified miRNAs (or 15.93%) and 380 novel miRNAs were classified as type 1 (Fig. 2). Most identified miRNAs overlapped with two REs, and three (miR-325, miR-649, and miR-5692b) overlapped with three REs. Interestingly, miR-649 consisted of three different RE families, including a LINE, short interspersed element (SINE), and DNA transposon. Those regions with three or more RE-derived miRNAs were more likely to be novel miRNAs. Three novel miRNAs (AC079412.1, AL158077.1, and AL356865.1) overlapped with five REs.

Precursor miRNAs form palindromic structures. Therefore, TE families with a palindromic sequence structure, including MITEs and MERs, have the potential to form mature miRNAs [2, 10, 11]. Both of these RE families may be able to form miRNA sequences themselves. Therefore, we assigned MITE-derived miRNAs and MER-derived miRNAs into the type 2 and type 3 categories, respectively.

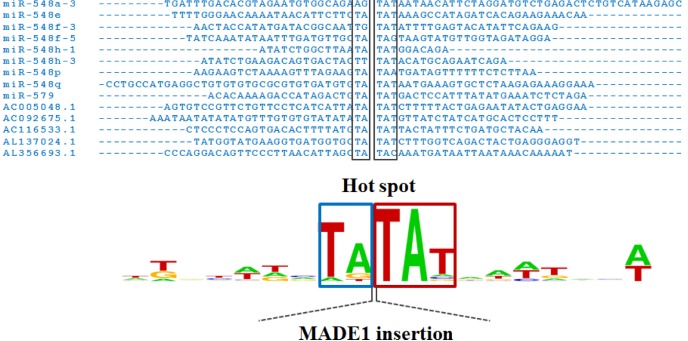

Type 2 precursor miRNAs were distinguished by the presence of MITEs, specifically MADE1, which consists of two 37-bp terminal inverted repeats flanked by 6 bps of the internal sequences; 390 regions were included in this category (20.53%) (Fig. 1B). For most type 2 miRNAs, the MADE1 sequences constituted more than 90% of the total miRNA sequences. These miRNA sequences may or may not have RE-derived sequences on both terminal sides, and miRNA precursors containing RE-derived sequences were classified as type 1. The palindromic sequence structure of MADE1 has the potential to form precursor miRNAs, and several studies identified mature MADE1-derived miRNAs. In previous studies, MADE1-derived miRNAs were identified as a part of the miR-548 gene family [2]. Seed shifting events in the miR-548 gene family were detected by evolutionary analysis [18]. According to our criteria, most genes in the miR-548 family were type 2 miRNAs, including seven miRNAs that were previously identified [2]. However, miR-548a-2 and miR-548a-3 were classified as type 1, because MADE1 sequences were inserted into RE sequences, and together, these RE sequences produce miRNA sequences.

Interestingly, MADE1-derived miRNAs are inserted into the specific (hot-spot) sequence TA-TAT or repetitive sequences, such as LINEs, long terminal repeat (LTR) elements, and other DNA elements. Some MADE1-derived miRNAs harbored hot-spot sequences (TA-TAT) in their miRNA gene sequences (Fig. 3). Therefore, MADE1-derived miRNAs likely formed the miR-548 family, known to be primate-specific [2, 18].

Type 3 precursor miRNAs were identified by the presence of MER sequences (14.05%, n = 267) (Fig. 1C). Most MER-derived miRNA precursor sequences overlapped with MER sequences, because MER palindrome sequences are similar to miRNA precursor sequences and may be able to form miRNA sequences themselves [11]. Notably, miR-1302-5 was classified as a type 1 precursor miRNA, because it combined two RE families (MER53 and AluSx).

Type 4 precursor miRNAs harbor one RE sequence (2.53%, n = 48) (Fig. 1D). Precursor miRNAs are approximately 60-80 nt [23]; so, it is unlikely for REs to occur in precursor miRNA sequences. Most type 4 miRNAs contained Low_complexity and Simple_repeat, because they tend to be relatively short. In the Simple_repeat family, a short repeat sequence helps to form miRNA precursor sequences by binding regions of complementary short repeat sequences. For example, miR-574 contains repeat (TG)n in its precursor regions (Supplementary Fig. 2A), and (TG)n sequences contain miR-574-5p sequences (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Type 5 precursor miRNAs were those formed from flanking sequences and one RE (9.63%, n = 183) (Fig. 1E). This category had the highest ratio of identified miRNAs to total miRNAs. The novel miRNA nomenclature process requires cloning or expression evidence. Then, this information is described in a manuscript accepted for publication [24, 25]. The identified miRNAs have a tendency to be abundantly and ubiquitously expressed in the host. Intriguingly, two RE families, SINE/mammalian-wide interspersed repeat (MIR) and LINE/L2, were commonly detected in type 5 miRNA precursor sequences. These two families were abundant in conserved segments and were commonly detected in murine intergenic regions of human orthologs [26]. These results indicate that the L2 and MIR TE families were highly conserved and that these RE-derived miRNAs have important functional roles in the host. Taken together, type 5 miRNAs are relatively abundant and evolutionarily conserved.

By contrast, type 6 precursor miRNAs, or those formed from a single RE, represented 29.47% of the sample (n = 560) (Fig. 1F). The REs contained in type 6 precursor miRNAs have the potential to produce miRNA sequences themselves. In type 6 miRNAs, SINE/Alu elements are the most common.

In this study, we classified miRNAs based on overlap patterns in identified miRNAs and novel miRNAs. In some cases, two or more REs were approached by "tail to tail" method and then making one miRNA precursor form. We classified these cases as type 1, and LINE/L1-derived miRNAs were abundantly discovered (Table 2). A previous study showed that miR-558 is derived only from MLT1C in the LTR family [9], but we found two repeat families (LTRs and simple repeats) in the locus. We also determined that miR-619 and miR-1302-5 were derived from the combination of two adjacent repeat families. Recently, the updated human genome assembly was open to the public (GRCh38/hg38), and novel REs have also been identified. Our classification of RE-overlapping miRNAs can provide the criterion to explain the origins, evolution, and family expansion of miRNAs in another human genome assembly or in other species.

In type 1 precursor miRNAs, some cases overlapped with the same families of TEs, which can make it possible to form an miRNA precursor form in a "tail to tail" scheme. In a previous study, two LINE elements were predicted to form in an oppositely oriented method, like hsa-miR-28 [12], and LINE was also the most abundant TE family in the type 1 miRNAs in our study. This result can help identify new miRNAs derived from two or more REs. MADE1s are broadly distributed among eukaryotes and function as regulatory RNAs in many genomes [27]. They are expressed with the gene sequences in which they are inserted. This phenomenon provides active opportunities for MADE1 hairpins to function through an RNA interference enzymatic mechanism involved in functional gene regulation [28]. We identified miRNAs that consisted of more than 90% MADE1 sequences and determined the specific mechanisms underlying the formation of MADE1-derived miRNA palindrome sequences.

Previous reports found 103 orthologs of the miR-1302 family in placental mammals. Moreover, the family has undergone multiple duplication events, and some of the duplicated genes have diverged functionally (e.g., RNA-based TE defense mechanisms), whereas others have become pseudogenes or have been eliminated from the genome [10]. Therefore, it has been suggested that the miRNA gene family evolved according to a birth-and-death model [10, 29, 30, 31].

Alu elements and miRNAs are related. Alu elements and those resulting from duplication events are induced to make new miRNAs and, specifically, an miRNA cluster on chromosome 19 (C19MC) [32]. C19MC presents primate-specific imprinted patterns in the placenta and may be an example of co-evolution between Alu elements and miRNAs [33, 34]. Alu elements are abundant in human chromosome 19; hence, miRNAs are also abundantly detected, including C19MC [32]. Most SINE elements, such as Alu, tRNAs, and 5s-rRNAs, are expressed by polymerase III (pol III), and several miRNAs are expressed by pol III. Some miRNAs are expressed together with Alu elements by pol III [35]. These data also demonstrate the strong relationship between miRNA and Alu elements.

In an evolutionary aspect, primate-specific miRNAs were discovered to contain an Alu element in their precursor form. Other small REs, such as tandem duplications, occupy the middle region of miRNA precursor forms. Therefore, type 4 miRNAs have abundant Simple_repeat families (Table 2). These data demonstrate that miRNAs have been made by genomic evolutionary events.

In conclusion, we determined that 1,900 RE-derived miRNAs can be divided into six major types. Of them, 406 identified miRNAs and 1,494 novel miRNAs were confirmed using the GENCODE database, and their RE patterns were sorted using the RepeatMasker program. The results suggest that RE sequences were interspersed throughout the genome and form miRNA precursor sequences that play important roles in the host genome. These regions may contribute to the evolution of biological complexity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by awards from the AGENDA project (Project No. PJ009254) in the National Institute of Animal Science, Rural Development Administration (RDA).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including one table and two figures can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-12-261-s001.pdf.

Supplementary Table 1

The total list of REs matched with miRNAs from the GENCODE database

Supplementary Fig. 1

Strategy for classification of transposable element (TE)-derived miRNAs used in this study.

Supplementary Fig. 2

(A) The genomic regions of the miR-574 precursor and repetitive elements. The miR-574 precursor is classified as Type 4; therefore, the repeat (TG)n is embedded in the miR-574 precursor sequence. (B) The secondary structure of the miR-574 precursor. The (TG)n repeat, miR-574-5p, and miR-574-3p sequences are indicated with a bar.

References

1. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004;116:281–297. PMID: 14744438.

2. Piriyapongsa J, Jordan IK. A family of human microRNA genes from miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements. PLoS One 2007;2:e203. PMID: 17301878.

3. Kim VN. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005;6:376–385. PMID: 15852042.

4. Hutvagner G, Simard MJ. Argonaute proteins: key players in RNA silencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008;9:22–32. PMID: 18073770.

5. Hedges DJ, Batzer MA. From the margins of the genome: mobile elements shape primate evolution. Bioessays 2005;27:785–794. PMID: 16015599.

6. Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Perspective: transposable elements, parasitic DNA, and genome evolution. Evolution 2001;55:1–24. PMID: 11263730.

7. Reiss D, Zhang Y, Mager DL. Widely variable endogenous retroviral methylation levels in human placenta. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:4743–4754. PMID: 17617638.

8. Sin HS, Huh JW, Kim DS, Kang DW, Min DS, Kim TH, et al. Transcriptional control of the HERV-H LTR element of the GSDML gene in human tissues and cancer cells. Arch Virol 2006;151:1985–1994. PMID: 16625320.

9. Piriyapongsa J, Mariño-Ramírez L, Jordan IK. Origin and evolution of human microRNAs from transposable elements. Genetics 2007;176:1323–1337. PMID: 17435244.

10. Yuan Z, Sun X, Jiang D, Ding Y, Lu Z, Gong L, et al. Origin and evolution of a placental-specific microRNA family in the human genome. BMC Evol Biol 2010;10:346. PMID: 21067568.

11. Ahn K, Gim JA, Ha HS, Han K, Kim HS. The novel MER transposon-derived miRNAs in human genome. Gene 2013;512:422–428. PMID: 22926102.

12. Borchert GM, Holton NW, Williams JD, Hernan WL, Bishop IP, Dembosky JA, et al. Comprehensive analysis of microRNA genomic loci identifies pervasive repetitive-element origins. Mob Genet Elements 2011;1:8–17. PMID: 22016841.

13. Piriyapongsa J, Jordan IK. Dual coding of siRNAs and miRNAs by plant transposable elements. RNA 2008;14:814–821. PMID: 18367716.

14. Saini HK, Griffiths-Jones S, Enright AJ. Genomic analysis of human microRNA transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:17719–17724. PMID: 17965236.

15. Smalheiser NR, Torvik VI. Mammalian microRNAs derived from genomic repeats. Trends Genet 2005;21:322–326. PMID: 15922829.

16. Zhang R, Peng Y, Wang W, Su B. Rapid evolution of an X-linked microRNA cluster in primates. Genome Res 2007;17:612–617. PMID: 17416744.

17. Jurka J, Kaplan DJ, Duncan CH, Walichiewicz J, Milosavljevic A, Murali G, et al. Identification and characterization of new human medium reiteration frequency repeats. Nucleic Acids Res 1993;21:1273–1279. PMID: 8464711.

18. Liang T, Guo L, Liu C. Genome-wide analysis of mir-548 gene family reveals evolutionary and functional implications. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012;2012:679563. PMID: 23091353.

19. Hertel J, Lindemeyer M, Missal K, Fried C, Tanzer A, Flamm C, et al. The expansion of the metazoan microRNA repertoire. BMC Genomics 2006;7:25. PMID: 16480513.

20. Yuan Z, Sun X, Liu H, Xie J. MicroRNA genes derived from repetitive elements and expanded by segmental duplication events in mammalian genomes. PLoS One 2011;6:e17666. PMID: 21436881.

21. Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, Tapanari E, Diekhans M, Kokocinski F, et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res 2012;22:1760–1774. PMID: 22955987.

22. Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010;26:841–842. PMID: 20110278.

23. Krol J, Sobczak K, Wilczynska U, Drath M, Jasinska A, Kaczynska D, et al. Structural features of microRNA (miRNA) precursors and their relevance to miRNA biogenesis and small interfering RNA/short hairpin RNA design. J Biol Chem 2004;279:42230–42239. PMID: 15292246.

24. Ambros V, Bartel B, Bartel DP, Burge CB, Carrington JC, Chen X, et al. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA 2003;9:277–279. PMID: 12592000.

26. Silva JC, Shabalina SA, Harris DG, Spouge JL, Kondrashovi AS. Conserved fragments of transposable elements in intergenic regions: evidence for widespread recruitment of MIR- and L2-derived sequences within the mouse and human genomes. Genet Res 2003;82:1–18. PMID: 14621267.

27. Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Transposable elements and host genome evolution. Trends Ecol Evol 2000;15:95–99. PMID: 10675923.

28. Liang Y, Ridzon D, Wong L, Chen C. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal human tissues. BMC Genomics 2007;8:166. PMID: 17565689.

29. Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 2004;432:231–235. PMID: 15531879.

30. Jordan IK, Miller WJ. Genome defense against transposable elements and the origins of regulatory RNA. (Lankenau DK, Volff JN, eds.). In: Genome Dynamics and Stability. Vol. 4. Transposon and the Dynamic Genome Heidelberg: Springer, 2009. pp. 77–94.

31. Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J 2002;21:4663–4670. PMID: 12198168.

32. Zhang R, Wang YQ, Su B. Molecular evolution of a primate-specific microRNA family. Mol Biol Evol 2008;25:1493–1502. PMID: 18417486.

33. Lehnert S, Van Loo P, Thilakarathne PJ, Marynen P, Verbeke G, Schuit FC. Evidence for co-evolution between human microRNAs and Alu-repeats. PLoS One 2009;4:e4456. PMID: 19209240.

34. Noguer-Dance M, Abu-Amero S, Al-Khtib M, Lefèvre A, Coullin P, Moore GE, et al. The primate-specific microRNA gene cluster (C19MC) is imprinted in the placenta. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:3566–3582. PMID: 20610438.

35. Gu TJ, Yi X, Zhao XW, Zhao Y, Yin JQ. Alu-directed transcriptional regulation of some novel miRNAs. BMC Genomics 2009;10:563. PMID: 19943974.

Fig. 1

Schematic of the precursor miRNAs derived from repetitive elements (REs) located in the genome. REs and precursor miRNAs are shown as horizontal bold bars and upper thin bars, respectively. The type 1 precursor miRNAs are formed by two adjacent REs (A). Type 2 precursor miRNAs are formed by MADE1 (B), whereas type 3 precursor miRNAs are formed by medium reiterated sequence (MER) (C). The type 4 precursor miRNAs contain RE sequences (D), and the type 5 precursor miRNAs are located between the flanking sequences and REs (E). The type 6 precursor miRNAs are retained within the RE sequences (F).

Fig. 3

Hot-spot sequences at both ends of MADE1 insertion sequences. MADE1 is inserted into TA-TAT sequences.

Table 1.

The number of REs-derived miRNAs and their rates

Table 2.

Distribution of RE-derived miRNAs by type

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 39 Crossref

- 6,245 View

- 82 Download