Concepts and definitions

Let ÎŁ = {A, C, G, T} be a set of DNA alphabets, where A, C, G, and T are called DNA characters or bases. A DNA sequence S is an ordered list of DNA alphabets. S is denoted by ăc1, c2, ..., clă, where ci â ÎŁ and |S| denotes the length of sequence S. A sequence with length n is called an n-sequence. A sequence database D is a set of tuples ăsid, Să, where sid is a sequence ID. The sum of the lengths of all sequences in D is denoted as |D|=|S1|+|S2|...|Sn|

Definition 1 (Patter)

A pattern is a contiguous sub-sequence of DNA sequence S drawn from ÎŁ = {A, C, G, T}. A sequence Îą = ăa1, a2, ..., ană is called a contiguous sub-sequence of another sequence β = ăb1, b2, ..., bmă, and β is a contiguous super-sequence of Îą, denoted as Îąâβ, if there exists integers 1 ⤠j1 ⤠j2 ⤠... ⤠jn ⤠m and ji+1 = ji + 1 for 1 ⤠i ⤠n-1 such that a1 = bj1, a2 = bj2, ..., an = bjn. We can also say that Îą is contained by β. In our paper, we use the term "(sub)-sequence" to describe "contiguous (sub)-sequence" in brief.

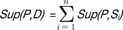

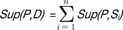

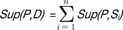

Definition 2 (Support)

Given a pattern

P and a sequence

S, the number of occurrences of

P in

S is called the

support of pattern

P in sequence

S, denoted as

Sup(P, Si). For DNA sequence database

D, the support of

P in

D is defined as

.

Definition 3 (Confidence)

Given a pattern P = P1, P2, ..., Pq and a DNA sequence database D, the confidence of P1P2 with respect to P1 is defined as Conf(P1P2, P1) = Sup(P1P2,D)/Sup(P1,D).

For example, the character "A" occurs 10 times and "AT" occurs 7 times, and in database

D in

Table 1,

Conf(AT,A) = 7/10 = 0.7.

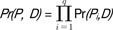

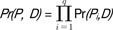

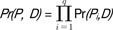

Definition 4 (Pattern probability)

Given a pattern

P =

P1,

P2, ...,

Pq (

Pi is a DNA alphabet) and a DNA sequence database

D, the

pattern probability of

P in

D is defined as

, where

Pr(Pi, D) = # of occurrences of an alphabet

Pi/|

D|.

For example, the

pattern probability of pattern "ATCG" in

Table 1 is

Pr(ATCG,D) =

Pr(A,D) Ă

Pr(T,D) Ă

Pr(C,D) Ă

Pr(G,D) =

(10/55) Ă

(18/55) Ă

(12/55) Ă

(15/55) =

0.182 Ă

0.372 Ă

0.218 Ă

0.273 =

0.00403.

Definition 5 (Information)

The information carried by a DNA character or base in DNA sequence database D is defined as I(c) = -log|C|Pr(c,D), where |C| is the number of distinct characters in D and Pr(c) is the probability of c occurs in D.

For example, the occurrence probability of character A in

Table 1 is

Pr(A,D) = # of

occurence(A)/|

D|. So, the probability of character A is

Pr(A,D) =

10/55 =

0.182 in our example database. Then, the

information of character A in

D is,

I(A) = -

log|C|Pr(A,D) = -

log4(0.182) =

1.228.

Definition 6 (Pattern information)

Given a pattern P = P1, P2, ..., Pq and a DNA sequence database D, the pattern information of P in D is defined as I(P) = -log|C|Pr(P,D) = I(P1) + I(P2) +......+ I(Pq).

For example, the

pattern information of pattern "ATCG" is

I(ATCG,D) =

I(A,D) +

I(T,D) +

I(C,D) +

I(G,D) =

1.228 +

0.713 +

1.098 +

0.9365 =

3.9755 in

Table 1.

Definition 7 (Information gain)

Given a pattern P = P1, P2, ..., Pq and a DNA sequence database D, the pattern information gain of P in D is defined as IG(P) = I(P) Ă Support(P).

For example, the

information gain of pattern "ATCG" is

IG(ATCG,D) =

3.9755

* 5 =

19.8775 in

Table 1.

Definition 8 (Finding interesting patterns)

Given a sequence database D and user-specified min_conf and min_in_gain, the problem of finding interesting patterns is to find the complete set of interesting patterns, such that IG(P) and Conf(P) are greater than min_in_gain and min_conf , respectively.

Surprising pattern-mining algorithm

The method for mining surprising contiguous patterns from a DNA sequence database proceeds as follows. For constructing the fixed length spanning tree, we follow the method suggested by Kang et al. [

12] - that is, read the database sequences and, starting from the first of each sequence, move the position one by one of the fixed length window throughout the sequence (

Fig. 1). We put the sequence ID and the starting position in the leaf node of the tree as a variable length array, in addition to the frequency of the pattern moving of the window.

Fig. 2 shows our proposed algorithm. It has two steps. The first step recursively scans the subsequence with the same length as the fixed-length window from the given sequences to construct a fixed-length spanning tree and put the database sequence ID and starting position of the pattern in the leaf node of tree as a one-side open variable length array. At this time, it calculates the character probabilities for A, C, G, and T, respectively. It is straightforward for the calculation of character probabilities for A, C, G, and T. By adding all occurrences of A, C, G, and T and dividing by the total number of characters in the database, it can be obtained easily. After calculating character probabilities, we can calculate character information, pattern information, and pattern information gain by using definition 5, definition 6, and definition 7.

The second step generates fixed-length patterns from the constructed spanning tree with satisfying the minimum information gain threshold and minimum confidence threshold, and expands sequences by joining candidates and checking the frequency and starting position of the candidates. At the time of joining the sequences with the same length to generate the candidates of the next length, it checks whether the second candidate starts right to the next position of the first one with the same ID or not. If so, it increases the frequency counter by one. Finally, it checks the minimum information gain and minimum confidence threshold. If the pattern satisfies both thresholds, then it is added to the next-length candidate pattern. This process is recursively followed for all the candidates with the same length to generate the next-length surprising candidates.

The spanning tree is shown in

Fig. 3, which is constructed based on the database available in

Table 1. We have constructed a fixed-length spanning tree using the method suggested by Zerin et al. [

13] but put the sequence ID and the staring position in the leaf node of the tree as a variable length array. Once the tree is constructed like

Fig. 3, retrieval of the tree can obtain contiguous subsequences with length-4, satisfying the satisfying minimum information gain threshold and minimum confidence threshold. Then, the obtained length-4 surprising contiguous patterns are ăATCGă, ăTCGTă, ăTGATă, ăCGTGă, ăCGTTă, ăCATCă, and ăGTGAă, shown in

Fig. 4.

To generate the length-5 surprising contiguous patterns, we need to join the length-4 surprising patterns; all the items in the first pattern, excluding the first item, should be same as all the items of the second pattern, excluding the last item. The frequency counter of the next length pattern will increase if both of the patterns are present in the same sequence and the second pattern's starting positions are the right next to the position of the first pattern in the same sequence. If the generated patterns satisfy the

min_in_gain and

min_conf, we consider the new pattern as a next length surprising candidate. The obtained length-5 surprising patterns are ăATCGTă, ăTCGTGă, ăTCGTTă, ăCGTGAă, ăCATCGă, and ăGTGATă. From

Fig. 2, we see pattern ATCG starts from the 1st and 11th positions of sequence 10, 2nd and 9th positions of sequence 20, and 2nd position of sequence 30.

The pattern TCGT starts from 3rd and 10th positions of sequence 20, 3rd position of sequence 30, and 1st position of sequence 40. As a result, the length-5 candidate ATCGT starts from the 2nd and 9th positions of sequence 20 and the 2nd position of sequence 30. So, the information gain of ATCGT is 14.065, and the confidence of ATCGT with respect to ATCG is 0.6, which satisfy both min_in_gain and min_conf thresholds.

Following the same process, the obtained length-6 surprising patterns are ăCGTGATă, ăCATCGTă, and ăTCGTGAă, and the obtained length-7 surprising pattern is ăTCGTGATă. Here, we scan the whole database only once to construct the fixed-length spanning tree and then never scan the database again. On the other hand, using an index-based method and

min_in_gain and

min_conf thresholds, our proposed approach consumes less memory and faster execution than Zerin et al. [

13].

.

. , where Pr(Pi, D) = # of occurrences of an alphabet Pi/|D|.

, where Pr(Pi, D) = # of occurrences of an alphabet Pi/|D|. .

. , where Pr(Pi, D) = # of occurrences of an alphabet Pi/|D|.

, where Pr(Pi, D) = # of occurrences of an alphabet Pi/|D|.