|

|

- Search

| Genomics Inform > Volume 14(3); 2016 > Article |

Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito borne pathogen, belongs to Flaviviridae family having a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome, currently known for causing large epidemics in Brazil. Its infection can cause microcephaly, a serious birth defect during pregnancy. The recent outbreak of ZIKV in February 2016 in Brazil realized it as a major health risk, demands an enhanced surveillance and a need to develop novel drugs against ZIKV. Amodiaquine, prochlorperazine, quinacrine, and berberine are few promising drugs approved by Food and Drug Administration against dengue virus which also belong to Flaviviridae family. In this study, we performed molecular docking analysis of these drugs against nonstructural 3 (NS3) protein of ZIKV. The protease activity of NS3 is necessary for viral replication and its prohibition could be considered as a strategy for treatment of ZIKV infection. Amongst these four drugs, berberine has shown highest binding affinity of –5.8 kcal/mol and it is binding around the active site region of the receptor. Based on the properties of berberine, more similar compounds were retrieved from ZINC database and a structure-based virtual screening was carried out by AutoDock Vina in PyRx 0.8. Best 10 novel drug-like compounds were identified and amongst them ZINC53047591 (2-(benzylsulfanyl)-3-cyclohexyl-3H-spiro[benzo[h]quinazoline-5,1'-cyclopentan]-4(6H)-one) was found to interact with NS3 protein with binding energy of –7.1 kcal/mol and formed H-bonds with Ser135 and Asn152 amino acid residues. Observations made in this study may extend an assuring platform for developing anti-viral competitive inhibitors against ZIKV infection.

Zika virus (ZIKV), belongs to family "Flaviviradae" having genus "Flavivirus" [1], is a mosquito-borne flavivirus. It transmits mainly through vectors from the Aedes genus and monkeys [2]. Humans get infected by infected mosquito bites or by direct contact probably during sexual intercourse [3]. Symptoms associated with the viral infection are fever, mild headache, malaise, conjunctivitis, rashes, and arthralgia. The illness by ZIKV is usually not much severe and there is a long-term symptoms for more than a few days to a week after infected by mosquito. As the mortality rate of ZIKV infection is very rare with less severe sickness, many people might not realize they have been infected. There is an augmented risk of microcephaly development along with severe fetal brain defects in the fetus of pregnant women when she infected with ZIKV [4]. In 1947, the ZIKV was first isolated from the blood of a sentinel rhesus monkey number 766 living in Zika forest at Uganda [2]. In 2007, ZIKV spreads from Africa and Asia to cause the largest outbreak in humans on Pacific island of Yap [5]. There are around 73% of yep residents over the age of 3 years were infected with ZIKV whereas no deaths were subjected [5,6].

The viral illness become apparent disease due to the increasing distribution area of ZIKV, confirming by the recent epidemic French Polynesia, new Caledonian since October 2013 [7] and crook island in March 2014. In May 2015, the Pan American Health Organization and World Health Organization (WHO) issued an epidemiological alert to ZIKV infection [8]. Brazilian health officials confirm a case of ZIKV infection transmitted by transfused blood from an infected donor in February 2016. There are two types of diagnosis for ZIKV are available, one is the detection of the virus and viral components through reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, immunoassay and virus isolation and the other one is based on the antibody detection extracted by ZIKV infection [6]. A preliminary diagnosis is also carried out based on patients clinical features, place and date of travel and activities. Laboratory diagnosis is generally able by testing serum or plasma to detect virus.

ZIKV consist of a single stranded, positive sense, 5'-capped RNA with genome size of around 11 kb which immediately released into the cytoplasm following by cell entry [9]. There are 59 and 39 un-translated regions along with only one open reading frame which codes a polyprotein that further cleaved into three structural proteins i.e., the capsid (c), envelope (E) and premembrane/membrane (prM); and seven nonstructural (NS) proteins i.e., NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 [10]. Among them the NS3 and NS5 proteins play a central role, together they harbor most of the catalytic activities needed for capping and replication [9]. The NS5 consist of an N-terminal methyl-transferase (NS5 MTase) domain, c-terminal RNA dependent, RNA polymerase (NS5 RdRp). Whereas NS3 is a multi-domain protein with an N-terminal NS3pro and c-terminal fraction containing the RNA triphosphatase (NS3 RTpase) and RNA helicase (NS3 hel) activities involves in viral RNA synthesis [11,12,13]. The 375 kDa flaviviral polyprotein precursor is processed by host proteases and a virus encoded protease activity localized at the N-terminal domain of NS3. Whereas at the junctions prM-E, C-prM, NS4A-NS4B, E-NS1 [14,15], and likely also NS1-NS2A [16], is carried out by the host signal peptidase located within the lumen of endoplasmic reticulum, the left over peptide bonds between NS2B-NS3, NS2A-NS2B, NS3-NS4A, and NS4B-NS5 are cleaved by NS3Pro. Cleavage at the NS2B/NS3 site is carried out in cis but is not essential for protease activity [17,18]. Thus, the protease activity of NS3 protein is very essential for viral replication and its inhibition has to be evaluated as a valuable approach for treatment against flaviviral infections [9]. Thus, the NS3 protein may be considered as important drug target. Currently, there is no medicines and vaccines developed against ZIKV or specific antiviral treatment for clinical ZIKV infection. Treatment is normally supportive and can include rest, intake of fluids, and use of antipyretics and analgesics [19].

There are some Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs such as: amodiaquine [20], prochlorperazine [21], quinacrine, and berberine [22], were reported to be effective (in vitro or in vivo) against dengue virus (DENV) which is also a Flavivirus. There are many things that dengue and Zika have in common like they both are mosquito borne viruses spread especially by the Aedes mosquito. Both have similar symptoms. The difference is that ZIKV symptoms last for few days or weeks and then they subside but for dengue the fever last for weeks and that can further lead to bruising and bleeding. Both dengue and Zika have three structural proteins and seven nonstructural. Quinacrine is also active against Ebola virus [23]. As ZIKV also belong to the Flaviviradae family, these drugs may have some therapeutic effect against ZIKV. Thus in this study, we have taken these four FDA approved drugs against DENV as ligands and performed molecular docking analysis against NS3 protein of ZIKV in order to observe the binding affinity of these drugs. Among these four drugs, the drug showing minimum binding energy has been considered as the lead drug for further analysis. Further, drug like compounds with similar physiochemical properties of the lead drug, have been retrieved from ZINC database for virtual screening against NS3 protein, in order to identify novel drugs for ZIKV.

The study was carried out on Dell Workstation with 2.26 GHz processor, 6 GB RAM and 500 GB hard drive running in Windows operating system. Bioinformatics software, such as PyRx 0.8 [24], Phyre2 [25], AutoDock Vina [26] and online resources like NCBI [27], ProCheck at RCSB validation server [28], ProSA-web [29], ZINC database (https://zinc.docking.org), ProQ [30], ERRAT server [31], etc. were used in this study.

The sequence of NS3 protein (accession No. YP_009227202) of ZIKV was retrieved from NCBI database [27]. Phyre2 servers predict the three-dimensional (3D) structure of a protein sequence using the principles and techniques of homology modeling. Because the structure of a protein is more conserved in evolution than its amino acid sequence, a protein sequence of interest (the target) can be modeled with reasonable accuracy on a very distantly related sequence of known structure (the template), provided that the relationship between target and template can be discerned through sequence alignment. Phyre2 was used for modelling the 3D structure of NS3 protein, it is a suite of tools available on the web to predict and analyze protein structure, function and mutations. The focus of Phyre2 is to provide biologists with a simple and intuitive interface to state-of-the-art protein bioinformatics tools [29]. The refined model reliability was assessed through, ProSA-web, the ProSA program (Protein Structure Analysis) is an established tool which has a large user base and is frequently employed in the refinement and validation of experimental protein structures [29], and ProQ is a neural network based predictor that based on a number of structural features predicts the quality of a protein model [30]. Further the refined model was verified by ERRAT server, ERRAT is a program for verifying protein structures determined by crystallography. Error values are plotted as a function of the position of a sliding 9-residue window. The error function is based on the statistics of non-bonded atom-atom interactions in the reported structure [31].

Chemical structures of ligands (amodiaquine, prochlorperazine, quinacrine, and berberine) used in this study were retrieved from the PubChem database [32]. PDBQT files of ligands and receptor molecules (NS3) was prepared. Then the protein-ligand docking studies were performed using the AutoDock Vina program [26]. It is one of the widely use method for protein-ligand docking. AutoDock Vina significantly improves the average accuracy of the binding mode predictions. For the input and output, Vina uses the PDBQT molecular structure file format. Here PDBQT file of four drugs were taken as ligand and PDBQT file of NS3 was taken as protein. These drug compounds were docked with NS3 protein of ZIKV and NS3 protein of DENV around its important binding site residues such as His51, Asp75, and Ser135.

Virtual screening is now well-known as an efficient prototype for filtering compounds for drug discovery. It was carried out using PyRx 0.8 (Virtual Screening Tools). All the drug-like compounds retrieved from ZINC database in SDF format in a single file. The SDF file was imported in open babel of PyRx and further energy minimization of all the ligands were performed followed by conversion of all the ligands into AutoDock PDBQT format. Further, these ligands were subjected to docking against NS3 protein of ZIKV using AutoDock Vina in PyRx 0.8 [26].

The NS3 protein (accession No. YP_009227202) of ZIKV has 617 amino acids residues and NS3 protein of DENV (accession No. NP_740321.1) has 618 amino acid residues in its protein sequence. The NS3 protein of both ZIKV and DENV have structurally similar with three conserve domain, i.e., FLAVIVIRUS_NS3PRO, Flavivirus NS3 protease (NS3pro) domain; HELICASE_ATP_BIND_1, superfamilies 1 and 2 helicase ATP-binding type-1 domain; and HELICASE_CTER, superfamilies 1 and 2 helicase C-terminal domain (predicted from ScanProsite tool of ExPASy) [33]; however, there are 67% identities and 100% similarities in their amino acid sequences obtained from BLASTP result [34].

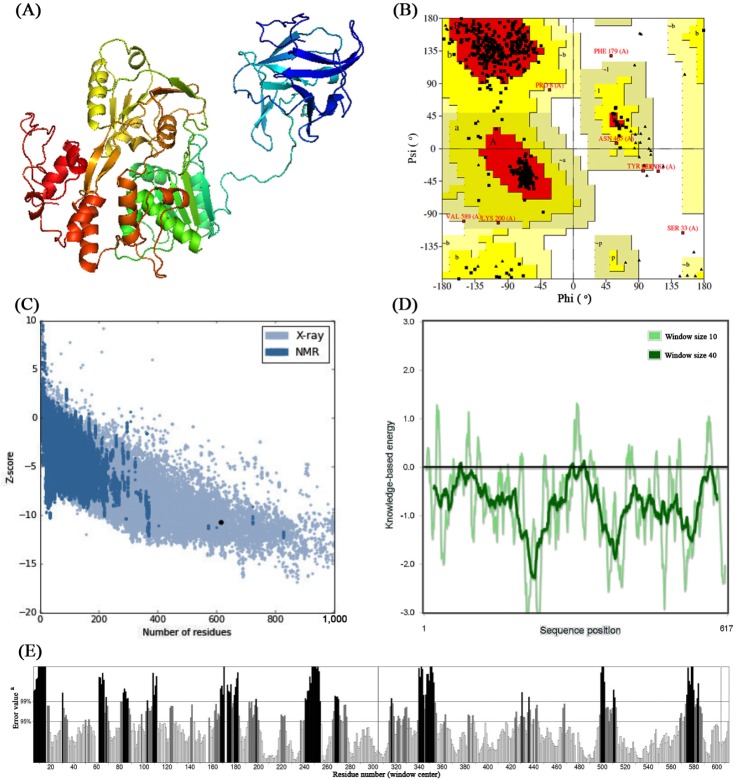

Three-dimensional structure of both NS3 proteins (Fig. 1A) were modeled using Phyre2 server which has taken chain A of 2VBC (crystal structure of the NS3 protease-helicase from DENV) as template for modeling having 100% confidence and 67% identity. From the ProCheck analysis obtained from Ramachandran plot (Fig. 1B), it was observed that 88.8% residues were located in most favorable region, 9.8% were in additional allowed region, 0.4% residues in generously allowed regions whereas 0.9% of the residues located in disallowed region. The compatible Z score value of –10.71 (Fig. 1C) obtained from ProSA-web evaluation revealed that the modelled structure is fit within the range of native conformation of crystal structures [29]. Further, the overall residue energies of NS3 was largely negative (Fig. 1D). The modelled NS3 protein of ZIKV showed Levitt-Gerstein (LG) score of 5.060 by Protein Quality Predictor (ProQ) tool, it implies the high accuracy level of the predicted structure and taken to account as extremely good model. The ProQ LG score of more than 2.5 is needed to proposing a predicted structure is of very good quality [30]. By using ERRAT plot same assumptions were achieved, where the overall quality factor is 67.002%. All of the above out comes recommended the reliability of the proposed model.

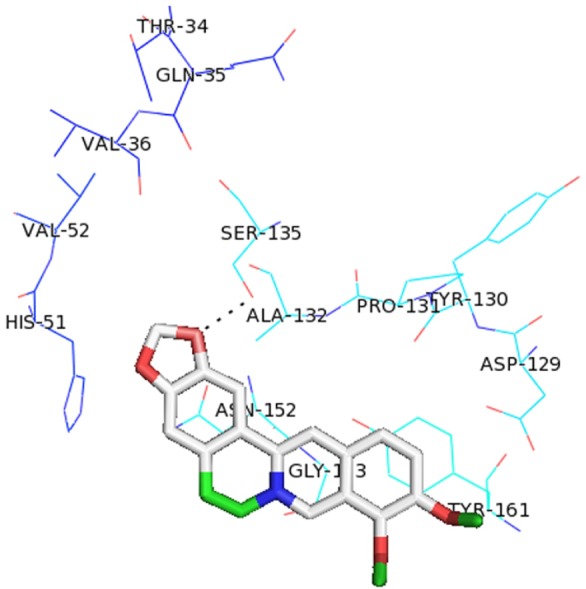

Different studies have already reported that the nonstructural NS3 protein is very essential for the development of the viral polyprotein and is a suitable target for designing antiviral inhibitors [32]. Analysis of the amino acid sequence of the NS3 protein of hepatitis C virus suggested that this viral protein contains a trypsin-like serine protease domain that functions in the processing of the viral polyprotein [35]. NS3 protein of ZIKV contains catalytic triad of His51, Asp75, and Ser135 [9]. The active site of serine proteases in variably contains three residues, histidine, aspartate, and serine that maintain the same relative spatial position in all the known structures of these enzymes. Thus, we performed molecular docking of four FDA approved drugs using AutoDock Vina [26] around the active site residues of NS3 protein of both ZIKV and DENV. From the docking analysis, it was observed that among all the drugs berberine showed the lowest binding energy in both ZIKV and DENV of –5.8 kcal/mol and –6.6 kcal/mol respectively. In ZIKV, berberine has formed hydrogen bond with Ser135 (Fig. 2). Likewise other three drugs, i.e., amodiaquine, prochlorperazine, and Quinacrine also docked with NS3 protein of both ZIKV and DENV with considerable binding energy (Table 1). From ZIKV protein-ligand docking we select the ligand having lowest binding energy then proceed for screening to get more similar drug like compounds.

The virtual screening technique is an economical, reliable and time saving method for screening large set of lead molecules. In our study, we have used PyRx 0.8 [24] for screening lead molecules against NS3 protein was used to solve the purpose. The NS3 protein of ZIKV was used as receptor to screen 4,121 drug-like compounds (small molecules) based on properties of berberine such as molecular weight of 336.367 g/mol, Xlog p-value of 0.20, net charge of 1, rotatable bonds 2, polar surface area 41Å2, hydrogen donor 0, hydrogen acceptor 5, apolar desolvation 8.91 kcal/mol, and polar desolvation of 8.91 kcal/mol. Further, an approximate range molecular weight ranges from (300 to 400 g/mol); Xlog p (0.10 to 0.50); net charge (–1 to 3); rotatable bonds (1 to 5); polar surface area (20 to 60 Å2); hydrogen donor (0 to 5); hydrogen acceptor (2 to 8); apolar desolvation (5 to 15 kcal/mol); and polar desolvation ranges from (–40 to –10 kcal/mol) was taken to retrieve similar drug compounds from ZINC database. AutoDock Vina [26] in PyRx 0.8 was employed for screening the ligands which generates nine distinct poses of each ligand. Further, based on the hydrogen bond interaction with active site residues of NS3, the docking pose for each ligand was selected.

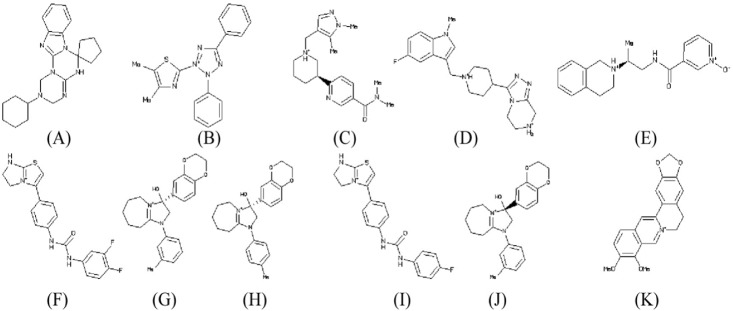

Top ten drug like compounds (Table 2) obtained by virtual screening bound to catalytic site of NS3 protein with lowest binding energy were taken as promising candidates for further analysis. All the ligand molecules observed to follow the Lipinski's rule of five (molecular weight not more than 500 Da; hydrogen bond donor not more than 5; hydrogen bond acceptors not more than 10; log p-value not greater than 5). The chemical structure of these ten compounds along with known inhibitor berberine are given in Fig. 3.

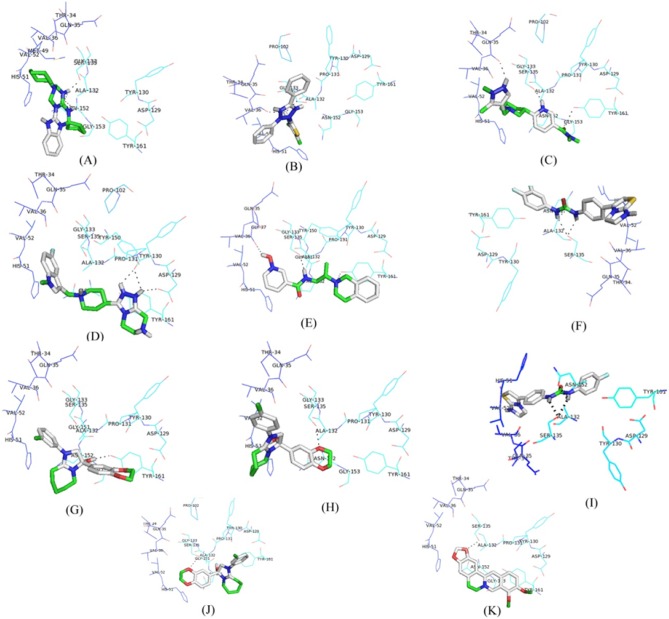

All the proposed lead molecules were observed to form hydrogen bonds with active site residues of NS3 protein (Fig. 4). The Lead 1 molecule is ZINC53047591(2(benzylsulfanyl)-3-cyclohexyl-3H-spiro[benzo[h]quinazoline-5,1'-cyclopent an]-4(6H)-one); having molecular weight 456.64218 (g/mol) showed the lowest binding of –7.1 kcal/mol and observed to interact with active site residues of NS3 by forming hydrogen bonds with SER135 and ASN152. The other nine lead molecules are also observed to inhibit NS3 protein with significant lower binding energy as compared to berberine. Thus, the higher binding affinity of selected lead molecules compared to berberine in respective docking complexes proposed that the selected ligands would probably bind more competitively in the active site of NS3 protein (Table 2).

The participation of selected lead molecules have very important role to inhibit the NS3 protein through hydrogen bonding interaction with its active site residues justified them as possible inhibitors against the important enzyme of ZIKV. Therefore, the given inhibitors may be demonstrated through biochemical assays.

In conclusion, the ZIKV belongs to Flaviviridae family, which is similar to DENV, West Nile virus and yellow fever virus. Currently, there are no specific drugs for prevention and treatment of ZIKV. As, the NS3 protein of this virus perform a central part in the viral life cycle, it is of appreciable interest in designing new potential drug candidate to deal with conquer the challenges of ZIKV infection. A high quality 3D structure of NS3 protein was predicted and validated through computational approach and molecular docking technique was employed to observe the interaction of the existing drugs used against other flavivirus, against ZIKV NS3 protein. Further, for identifying novel inhibitors, high-throughput virtual screening approach was employed in this study, would be of significant in designing new drugs for ZIKV infection.

Acknowledgments

Authors express gratitude to the Department of Biotechnology, MoS&T, Government of India for their financial support to Bioinformatics Centre wherein this study has been carried out. Grateful thanks to Shri D.S. Mehta, President, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. B.S. Garg, Secretary, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. K.R. Patond, Dean, MGIMS; Dr. S.P. Kalantri, Medical Superintendent, Kasturba Hospital, MGIMS, Sevagram & Dr. B.C. Harinath, Director, JBTDRC & Coordinator, Bioinformatics Centre for their encouragement & support.

References

1. Thiel JH, Collet MS, Gould EA, Heinz FX, Meyers G, Fauquet CM, et al. Family Flaviviridae. (Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, eds.). In: Virus Taxonomy: Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press, 2005. pp. 981–998.

3. Foy BD, Kobylinski KC, Chilson Foy JL, Blitvich BJ, Travassos da Rosa A, Haddow AD, et al. Probable non-vector-borne transmission of Zika virus, Colorado, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2011;17:880–882. PMID: 21529401.

4. Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IM, Horovitz DD, Cavalcanti DP, Pessoa A, et al. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly-Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:59–62. PMID: 26820244.

5. Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, Powers AM, Kool JL, Lanciotti RS, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2536–2543. PMID: 19516034.

6. Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Velez JO, Lambert AJ, Johnson AJ, et al. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1232–1239. PMID: 18680646.

7. Haddow AJ, Williams MC, Woodall JP, Simpson DI, Goma LK. Twelve isolations of Zika virus from Aedes (Stegomyia) africanus (Theobald) taken in and above a Uganda forest. Bull World Health Organ 1964;31:57–69. PMID: 14230895.

8. Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Americas. Zika virus infection. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, 2015. 2015 May 7. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=30075=en.

9. Bollati M, Alvarez K, Assenberg R, Baronti C, Canard B, Cook S, et al. Structure and functionality in flavivirus NS-proteins: perspectives for drug design. Antiviral Res 2010;87:125–148. PMID: 19945487.

10. Baronti C, Piorkowski G, Charrel RN, Boubis L, Leparc-Goffart I, de Lamballerie X. Complete coding sequence of Zika virus from a French Polynesia outbreak in 2013. Genome Announc 2014;2:e00500–e00514. PMID: 24903869.

11. Furuichi Y, Shatkin AJ. Viral and cellular mRNA capping: past and prospects. Adv Virus Res 2000;55:135–184. PMID: 11050942.

12. Egloff MP, Benarroch D, Selisko B, Romette JL, Canard B. An RNA cap (nucleoside-2'-O-)-methyltransferase in the flavivirus RNA polymerase NS5: crystal structure and functional characterization. EMBO J 2002;21:2757–2768. PMID: 12032088.

13. Ray D, Shah A, Tilgner M, Guo Y, Zhao Y, Dong H, et al. West Nile virus 5'-cap structure is formed by sequential guanine N-7 and ribose 2'-O methylations by nonstructural protein 5. J Virol 2006;80:8362–8370. PMID: 16912287.

14. Speight G, Coia G, Parker MD, Westaway EG. Gene mapping and positive identification of the non-structural proteins NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4B and NS5 of the Flavivirus Kunjin and their cleavage sites. J Gen Virol 1988;69(Pt1):23–34. PMID: 2826667.

15. Nowak T, Färber PM, Wengler G, Wengler G. Analyses of the terminal sequences of West Nile virus structural proteins and of the in vitro translation of these proteins allow the proposal of a complete scheme of the proteolytic cleavages involved in their synthesis. Virology 1989;169:365–376. PMID: 2705302.

16. Falgout B, Markoff L. Evidence that Flavivirus NS1-NS2A cleavage is mediated by a membrane-bound host protease in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol 1995;69:7232–7243. PMID: 7474145.

17. Leung D, Schroder K, White H, Fang NX, Stoermer MJ, Abbenante G, et al. Activity of recombinant dengue 2 virus NS3 protease in the presence of a truncated NS2B co-factor, small peptide substrates, and inhibitors. J Biol Chem 2001;276:45762–45771. PMID: 11581268.

18. Bera AK, Kuhn RJ, Smith JL. Functional characterization of cis and trans activity of the Flavivirus NS2B-NS3 protease. J Biol Chem 2007;282:12883–12892. PMID: 17337448.

19. Services Yap State Department of Health. Zika Virus: Information for Clinicians and Other Health Professionals. Yap: Yap State Department of Health, 2007.

20. Boonyasuppayakorn S, Reichert ED, Manzano M, Nagarajan K, Padmanabhan R. Amodiaquine, an antimalarial drug, inhibits dengue virus type 2 replication and infectivity. Antiviral Res 2014;106:125–134. PMID: 24680954.

21. Simanjuntak Y, Liang JJ, Lee YL, Lin YL. Repurposing of prochlorperazine for use against dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis 2015;211:394–404. PMID: 25028694.

22. Shum D, Smith JL, Hirsch AJ, Bhinder B, Radu C, Stein DA, et al. High-content assay to identify inhibitors of dengue virus infection. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2010;8:553–570. PMID: 20973722.

23. Ekins S, Freundlich JS, Clark AM, Anantpadma M, Davey RA, Madrid P. Machine learning models identify molecules active against the Ebola virus in vitro. F1000Res 2015;4:1091. PMID: 26834994.

24. Dallakyan S, Olson AJ. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol 2015;1263:243–250. PMID: 25618350.

25. Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc 2009;4:363–371. PMID: 19247286.

26. Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010;31:455–461. PMID: 19499576.

27. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Bethesda: U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2016. 2016 Jan 15. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

28. Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr 1993;26:283–291.

29. Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:W407–W410. PMID: 17517781.

30. Wallner B, Elofsson A. Can correct protein models be identified? Protein Sci 2003;12:1073–1086. PMID: 12717029.

31. Colovos C, Yeates TO. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci 1993;2:1511–1519. PMID: 8401235.

32. Wang Y, Bolton E, Dracheva S, Karapetyan K, Shoemaker BA, Suzek TO, et al. An overview of the PubChem BioAssay resource. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:D255–D266. PMID: 19933261.

33. de Castro E, Sigrist CJ, Gattiker A, Bulliard V, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Gasteiger E, et al. ScanProsite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:W362–W365. PMID: 16845026.

34. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990;215:403–410. PMID: 2231712.

35. Miller RH, Purcell RH. Hepatitis C virus shares amino acid sequence similarity with pestiviruses and flaviviruses as well as members of two plant virus supergroups. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990;87:2057–2061. PMID: 2156259.

Fig. 1

(A) Three-dimensional structure of predicted nonstructural 3 (NS3) protein model of Zika virus (ZIKV). (B) Ramachandran plot of predicted NS3 model. (C) ProSA-web Z-scores of all protein chains in Protein Data Bank determined by X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with respect to their length. The Z-score of NS3 was present in that range represented in dot. (D) Energy plot for the predicted NS3 protein of ZIKV. (E) ERRAT plot for residue-wise analysis of homology model. aOn the error axis, two lines are drawn to indicate the confidence with which it is possible to reject regions that exceed that error value.

Fig. 3

Chemical structure of 10 best lead molecules: ZINC53047591 (A), ZINC13510840 (B), ZINC19705600 (C), ZINC19711173 (D), ZINC25634061 (E), ZINC98342354 (F), ZINC02974658 (G), ZINC04086851 (H), ZINC98342344 (I), ZINC02974656 (J), and known inhibitor berberine: ZINC03779067 (K).

Fig. 4

Docking interaction structure of 10 best lead molecules and known inhibitor berberine along with hydrogen bonds: ZINC53047591 (A), ZINC13510840 (B), ZINC19705600 (C), ZINC19711173 (D), ZINC25634061 (E), ZINC98342354 (F), ZINC02974658 (G), ZINC04086851 (H), ZINC98342344 (I), ZINC02974656 (J), and berberine: ZINC03779067 (K).

Table 1.

Docking result of four Food and Drug Administration approved drugs against NS3 protein of ZIKV and DENV

Table 2.

Docking result of ten best lead molecules against NS3 protein of Zika virus along with berberine

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 47 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 9,771 View

- 197 Download

- Related articles in GNI